Talking Points - Donald Insall

Francis Maude of Donald Insall tells us about the finer points of conservation work

Words by Francis Maude

I have been asked ‘What sets repairs and restoration apart from the majority of commercial work?’

One key aspect lies in the choice and use of materials. Many of the buildings on which we work are pre-industrial. The hand-made, uneven surface of historic glass, wrought iron, old beams and dressed stone show the life, spirit, skill and enterprise of their makers. We respect that, and one of our greatest joys is that of working with really skilled craftspeople who can make beautiful things out of base materials. It’s craft as art.

To be able to run conservation projects successfully requires a wide skill set that encompasses an understanding of the analysis and selection of materials and of their workmanship. This is reflected in the kind of CPD which conservation architects do. There are many courses run by the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings, the Building Limes Forum and others that support both craftspeople and architects in learning about the specification and use of materials in conservation work.

There are ongoing university-based research projects into lime-based mortars and plasters and the complex interaction between the binder and the aggregate. Coupled with the analysis of historic mortars (which can be done by a laboratory for a modest sum, and so is affordable for the average project), it is possible to design a mortar to achieve a desired combination of appearance, speed of set, vapour permeability and compressive strength. In a re-pointed wall, the pointing mortar needs to be sacrificial, to decay preferentially to the retained brick and stone. So, in looking back to the materials and the workmanship in the buildings we seek to protect, we look forward to them surviving into the future as living buildings.

Of equal interest are the solid surfaces of the dressed stone. Sawn or honed are not the only finishes available, nor the most exciting to look at. Consider punched, boasted, reticulated or vermiculated options.

‘A man that looks on glass / on it may stay his eye/ or if he pleaseth through it pass / and then the heaven espy…’ wrote the early-17th-century priest-poet George Herbert. The appreciation of glass as both a surface with a characteristic ripple, reflection and colour, and as a transparent substance to see through, elevates glass to a more interesting material than we commonly regard it.

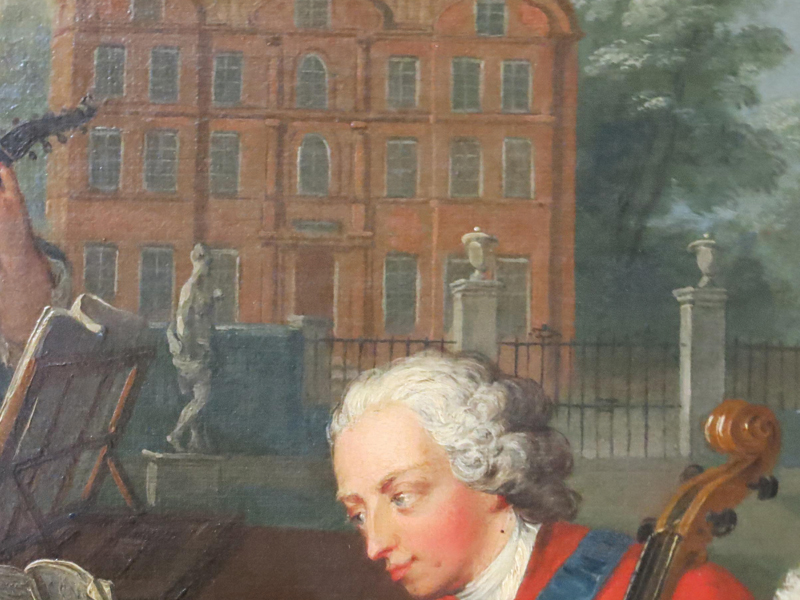

There are the specialist stained-glass studios that serve our great cathedrals, but we are equally delighted by windows from the 19th century and earlier that retain their crown and cylinder glass – neither of the two now readily obtainable. Conserving old buildings often brings surprises. At Kew Palace, we discovered traces of limewash, which were analysed and the results used to formulate a new coating for the building. This surface unified the brick mouldings throughout the structure to make the architecture easier to appreciate, as well as resolving for us the conundrum of why it had been represented in such odd seeming colours in an 18th-century painting.

Each project is a process of discovery, comprising observation, analysis, trial samples, specification and then the site work of conservation repair and making good that will bring a historic building back to life, keeping it as a ‘living building’.