Profile - Simon Allford

Simon Allford, architect and co-founder of Allford Hall Monaghan Morris, and one of the VIP line-up of speakers in this year’s FX Talks, tells us about the role of architects and an eight-year research project

Words by Emily Martin

It’s hard to believe that seven months have passed since our FX Talks made its debut, for which a series of innovators were invited to deliver a Ted-style talk to a ticketed audience on radical thinking, and what it means to be a radical thinker or doer.

I caught up with architect and FX Talks presenter Simon Allford, of Allford Hall Monaghan Morris (AHMM) architecture practice, to not only reflect on a fabulous evening enjoyed by all, but to also reignite the excitement as we gear up for the second edition of FX Talks in 2018.

‘Architects don’t have a responsibility to be radical. They need to think fundamentally about what are the problems that exist [when tackling a project], rather than “here are some buildings”,’ says Allford as we meet at AHMM’s London-based practice office, in Old Street. Our meeting takes place shortly after the practice’s deliverance of the White Collar Factory, a 16-storey mixed-use development, complete with a running track on the roof, also on Old Street.

‘In that sense architects aren’t radical enough; because of fees and everything else they try to put buildings forward as a solution before they even know whether a building is needed,’ he continues. ‘That’s the big question and, of course, if a building is needed then how might you make it and how might you engage people in discussion with it? But the first thing is exploring what are the underlying issues.’

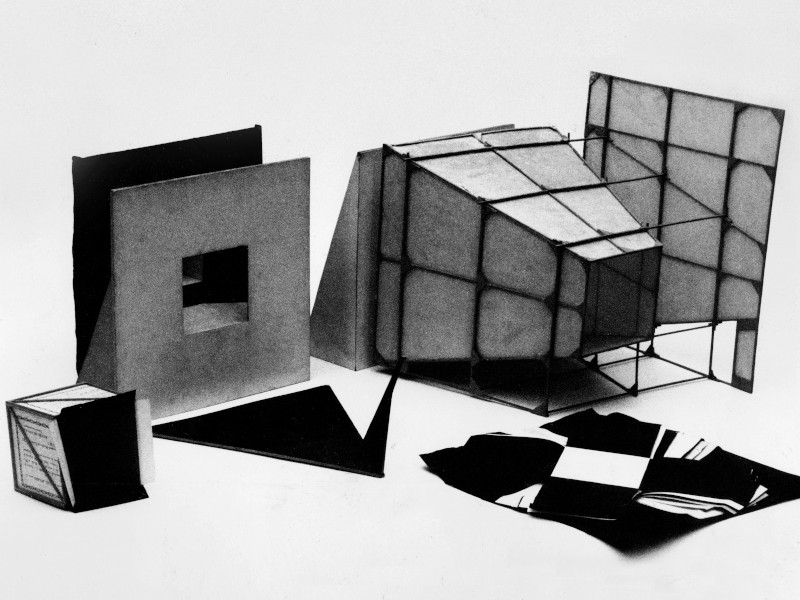

The mixed-use development is the culmination of an eight-year research project led by Allford, Simon Silver and Paul Williams – directors of developer Derwent London – working in collaboration with engineering firms AKT II and Arup. The research analysed why 19th-century warehouses and factory buildings have enjoyed such longevity, and how these structures could inform and inspire a sustainable development.

It identified five key elements: high ceilings, deep plans, simple passive facades, concrete structure, and smart servicing, all to become the driving principles behind White Collar Factory. The building design draws its inspiration from the work of French designer Jean Prouvé, whose design ethos is led by logic, balance and purity.

Running track on the roof of the White Collar Factory

Running track on the roof of the White Collar Factory

And while it was deemed necessary to demolish the pre-existing, low-rise building to make way for this higher rise version, critics may be keen to point out its much more profitable status in a part of London currently seeing a surge in tall buildings. Are we not demolishing too many low-rise buildings in favour of high-rises?

‘I don’t think we are demolishing a huge amount of building in London,’ counters Allford. ‘We are reusing or reinventing a certain amount of building stock, but there is another thing going on, where we are building a large number of tall buildings and I haven’t really got a problem with that: if they’re tall, they are seen by more people; if they’re residential, they last longer as they’re almost impossible to demolish, whereas an office can come and go; therefore, they need to be of better quality.

In my opinion the issue is quality, not height.’ And not just quality. Allford is keen to ensure buildings, such as the much-adored 19th-century warehouses, are loved within a streetscape both now and in years to come, as discussed during his FX Talks address when he spoke of ‘the world of the everyday buildings’. An AHMM ethos is to ‘achieve delight’ in these buildings for the people using them and by incorporating them into the streetscape, blurring the lines between what is public and private space. The White Collar Factory building features public areas, such as gardens, encouraging people to come, sit and use. But this is on private, Derwent-owned, land, so how does an architect encourage a client to let Joe Public on to its property?

‘If you make a build “of the city”, and by that I mean the place, you connect it with the public realm and open it up. Without anyone even knowing, it becomes a building that is engaged in a much more positive way,’ says Allford. ‘There’s always been a public and private interface, but the reality is if a hotel can feel more public and have security at the lifts, why can’t an office?’

Lobby space at the White Collar Factory: how easily can the public walk in and use it

Lobby space at the White Collar Factory: how easily can the public walk in and use it

As with museums, parks and libraries, these spaces are typically privately owned yet often viewed as public space, but purposefully designed to be used like this; each has incorporated a long lifespan into their original blueprint. And it’s this, Allford says, where architecture today falls down.

‘If there is an average, then half of the architecture produced is below-average. The reality is there isn’t perhaps enough commitment to long-term quality,’ he says. ‘We tend to work with clients who build, retain and own their buildings and so have a view of the longer term. If a building is well built and lasts well into the future it can flex from being residential to office, so we really have to think much more intelligently about providing better and more generous buildings.

‘The trouble is that people, including the Government, look at the outturn cost [to produce a building]; we really have to be looking at the cost of the building in 100 years’ time. If you look at this cost over a longer period then the likelihood is you’ll spend more at the beginning to get it right and less in the future maintaining it, which is the right way to go.’