Blueprint innovation: 16 interviews with international architects

Fuensanta Nieto & Enrique Sobejano

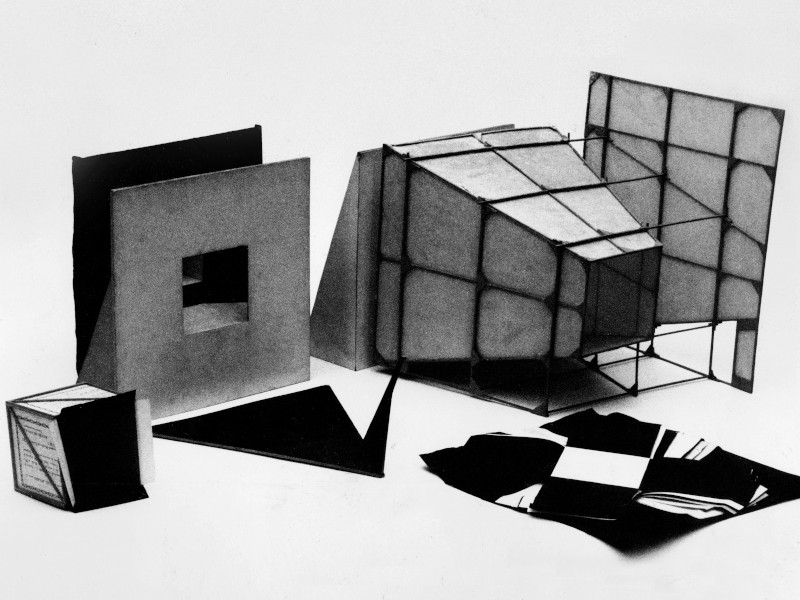

Fuensanta Nieto & Enrique Sobejano. Photo: L Sevillano

Fuensanta Nieto and Enrique Sobejano (Nieto Sobejano Arquitectos) believe that invention cannot be separated from memory. Winner of the 2015 Alvar Aalto Medal, the Madrid-based duo has gained further recognition by winning the international competition to design a study centre for composer Arvo Pärt in the middle of an Estonian forest. Inspired by literature, film, philosophy and Spain’s Islamic past, they experiment with geometric pattern sequences and visual associations, often adopting an interdisciplinary approach.

Although the Latin etymology ‘innovatio’ stands for the act of creating something new, in Spanish ‘innovación’ is defined as the creation or modification of a product. In that sense, ‘modification’ seems to be closer to how we understand it in architectural terms.

Innovation in architecture often means to transform the existent into something completely new. In our work we are interested in innovation in two aspects. One is more linked to the discipline - trying to conceive projects as a result of a different approach to something that previously existed. The other aspect refers to materiality and technology. In this sense we like to investigate new possibilities for materials and techniques from different points of view, for example working not only with manufacturing companies but also with artists who have a diverse vision.

We would like to think that architecture and science go hand in hand, but usually it is not so. Scientific and technological innovations tend to emerge in other fields first. Often new materials are originated in the aerospace, military, nautical or biological industries, etc. Architecture incorporates such inventions later, and transforms them into new building features.

In some cases, these appropriations illuminate new ways of expression. Steel and concrete are well-known examples of the Industrial Revolution and its influence on modern architecture. Today, advances that are related to energy consumption, reduction and sustainability may break ground for the next architecture.

The responsibility of the architect has many facets. In the first place it refers to the inhabitants, the city and the landscape. But it should essentially aim to improve the conditions of life, the conservation of the environment as well as respect for history. The possibility of truly inventing in the field of new materials is exceptional, and rarely does an architect manage to achieve it. Our work focuses rather on modifying materials, in other words, using them in unexpected ways.

For us, innovation is not an end per se. Some traditional materials and techniques - lost or forgotten - can be paradoxically innovative, since they can recover their value in our contemporary context. For example, in a museum project in Marrakech, we are investigating walls of rammed earth in unusual dimensions. In another project, for a visitors’ centre in India, we are proposing a large flat roof using the local Delhi red stone, carved digitally. Working with artists has helped us to discover new possibilities of expression. In San Telmo Museum, in San Sebastián, the interaction with the sculptors Ferrán and Otero resulted in a facade that we would probably not have imagined alone - a cross between architecture, a piece of art and nature. It is made from cast aluminium panels with elliptical perforations that are combined in multiple ways and allow for the growth of vegetation.

For the Córdoba Contemporary Art Centre, working with realities: united [realU], we have designed and built a dynamic facade that hides any technical element [lighting fixtures, glass, etc]. ‘Magically’, the white prefabricated concrete facade glows at night. In the city of Guangzhou, in China, we are currently planning a science museum that combines two different technologies: ceramic, belonging to the Chinese tradition, and a contemporary industrialised concrete system reinforced with glass.

Architecture, art and nature come together in the facade of San Telmo Museum, in San Sebastián, Spain. Photo: Roland Halbe

Finally, in the Arvo Pärt Centre in Estonia, the connection with art is different: the project respects the landscape, preserving the existing large pine trees, and proposes a sequence of pentagonal courtyards in a series that evokes certain musical pieces - variations on a single theme - to generate a conversation between music and architecture.

In certain cases we have described our work as a balance between memory and invention. This last term - invention - may be associated with innovation, but with an added meaning. In Spanish, ‘invención’ means invention, but also fiction. Since we are not interested in repeating the past - that would not make any sense - the concept of invention can be assimilated to the fiction of something that we perceive as new, but which in fact already existed used differently in the past.

Being honest, real innovation occurs only rarely. It develops slowly from project to project, and sometimes happens unexpectedly, recalling the famous Picasso quote: ‘We do not search for innovation, but we sometimes find it.' CF