Architecture and Film: Munio Weinraub and Amos Gitai

[caption id="attachment_3999" align="alignnone" width="504" caption="Munio Weinraub and Al. Mansfeld’s T-Block Building, Ramat Hadar, Haifa, 1958-63"] [/caption]

The dialogue between two generations and two art forms, architecture and film, examined in this vast and fascinating exhibition, informs an ongoing debate that continues to divide opinion within Israel. It emerges from the work of Munio Weinraub and his son Amos Gitai. Weinraub, who emigrated from Silesia, Germany in 1934, to the northern worker city of Haifa in Israel is widely considered to be the father of the Israeli modernist movement.

His buildings and urban planning laid the foundations of the modern Israeli state, appropriating the progressive modernist design idiom to symbolise the birth of a nation.Inspired by his teacher and mentor, Mies Van Der Rohe, Weinraub’s functional design was based on the needs of its users.

Typically, his developments – kibbutzim, industrial plants and private dwellings – were characterized by the integration of space and materials to create a feeling of security and wholeness. A socialist at heart, the designs for his community neighbourhood centres were based on the British working men’s clubs of the 1900s, which were built as a counterbalance to the exclusive clubs for the upper classes. His multifunctional halls rejected all forms of bourgeois representation.

Weinraub was familiar with Soviet worker’s clubs and designed cooperative settlements as well as his famous cubic workers’ homes in Haifa, known to this day as the Jewish worker city. He chose to live in Haifa because it suited his pronounced social awareness and, under the British mandate, Haifa soon developed into the country’s industrial centre.

His son Amos Gitai (the family changed its name to Gitai, the Hebrew translation of the German name Weinraub) initially followed in his father’s footsteps, training to become an architect, but when the Yom Kippur War interrupted his studies in 1973 he joined the army. During the war he started filming with a Super-8 camera given to him by his mother. On his 23rd birthday, his helicopter was shot down by a Syrian missile. Although he survived, this traumatic experience forced him to quit architecture altogether and move to filmmaking. He made a documentary about the incident and his fellow survivors, Kippur: War Memory in 1993, then a fictional recreation, Kippur, in 2000.

Often revered as one of Israel’s most important filmmakers, Gitai’s work represents the mindset of the self-critical second generation, one that is more willing to examine a multitude of experiences: Israeli and Palestinian, European and Middle Eastern.

Through incisive humour, poetry and music, his documentaries and feature films use homes and buildings as metaphors for Israeli and Middle Eastern society, while exploring how the relationships between family members and individuals can mirror the relationship between citizens and the state.

[caption id="attachment_4000" align="alignnone" width="560" caption="Still from Amos Gitai’s 2004 film, Promised Land"]

[/caption]

The dialogue between two generations and two art forms, architecture and film, examined in this vast and fascinating exhibition, informs an ongoing debate that continues to divide opinion within Israel. It emerges from the work of Munio Weinraub and his son Amos Gitai. Weinraub, who emigrated from Silesia, Germany in 1934, to the northern worker city of Haifa in Israel is widely considered to be the father of the Israeli modernist movement.

His buildings and urban planning laid the foundations of the modern Israeli state, appropriating the progressive modernist design idiom to symbolise the birth of a nation.Inspired by his teacher and mentor, Mies Van Der Rohe, Weinraub’s functional design was based on the needs of its users.

Typically, his developments – kibbutzim, industrial plants and private dwellings – were characterized by the integration of space and materials to create a feeling of security and wholeness. A socialist at heart, the designs for his community neighbourhood centres were based on the British working men’s clubs of the 1900s, which were built as a counterbalance to the exclusive clubs for the upper classes. His multifunctional halls rejected all forms of bourgeois representation.

Weinraub was familiar with Soviet worker’s clubs and designed cooperative settlements as well as his famous cubic workers’ homes in Haifa, known to this day as the Jewish worker city. He chose to live in Haifa because it suited his pronounced social awareness and, under the British mandate, Haifa soon developed into the country’s industrial centre.

His son Amos Gitai (the family changed its name to Gitai, the Hebrew translation of the German name Weinraub) initially followed in his father’s footsteps, training to become an architect, but when the Yom Kippur War interrupted his studies in 1973 he joined the army. During the war he started filming with a Super-8 camera given to him by his mother. On his 23rd birthday, his helicopter was shot down by a Syrian missile. Although he survived, this traumatic experience forced him to quit architecture altogether and move to filmmaking. He made a documentary about the incident and his fellow survivors, Kippur: War Memory in 1993, then a fictional recreation, Kippur, in 2000.

Often revered as one of Israel’s most important filmmakers, Gitai’s work represents the mindset of the self-critical second generation, one that is more willing to examine a multitude of experiences: Israeli and Palestinian, European and Middle Eastern.

Through incisive humour, poetry and music, his documentaries and feature films use homes and buildings as metaphors for Israeli and Middle Eastern society, while exploring how the relationships between family members and individuals can mirror the relationship between citizens and the state.

[caption id="attachment_4000" align="alignnone" width="560" caption="Still from Amos Gitai’s 2004 film, Promised Land"] [/caption]

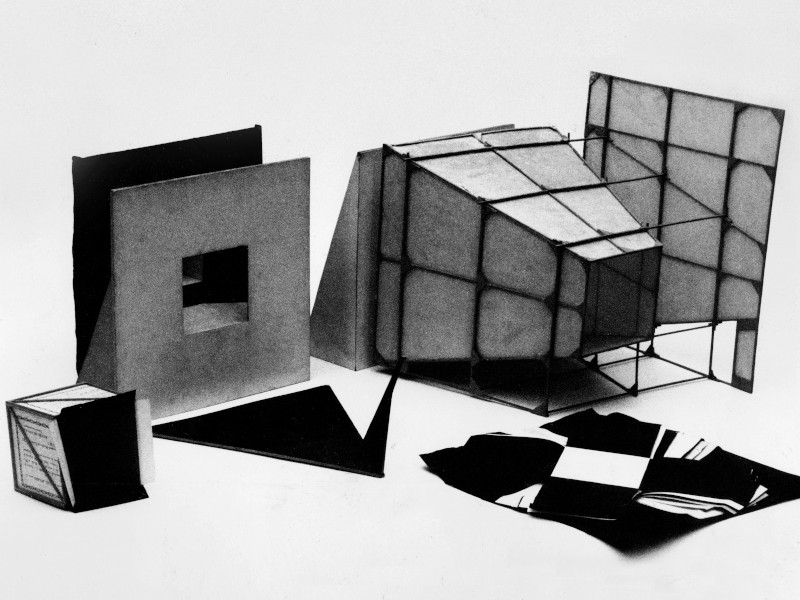

Walking through the display of Weinraub’s architectural models and documents, including original letters of acceptance from the Bauhaus school as well as beautifully detailed plans for his worker homes, the disturbing wail of voices from Gitai’s projected work adds an almost ghostly, dissonant note to the historic and turbulent project of modern Israel.

In the past, some Israelis have dismissed Weinraub’s Bauhausinspired architecture because of its associations with austerity. With its clean and simple lines, the architecture represented the rational foundation of the state. Yet since Tel Aviv was designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2003, attitudes are changing once again.

Celebrating the city’s centenary this year, the reappropriation of the White City – thus named for its proliferation of Bauhaus-style buildings – is considered by some to be a historically revisionist project. In his book White City Black City, left-wing architect and lecturer Sharon Rotbard argues that there is more than simple praise for the Bauhaus legacy at play here.

Rotbard implies that the current focus on the White City is partly a smokescreen for the elimination of Arab heritage in Jaffa, out of which Tel Aviv originally grew. After the 1948 War of Independence many Arabs fled or were removed from the area when they were attacked by insurgents from neighbouring states. In the 1960s when Jaffa was redeveloped as an artist’s enclave its previous residents were apparently not invited to return.

Although Rotbard’s particular concerns are not represented in the show, there is much here to inform and provoke in this marvelous and exhaustive exhibition. Weinraub (who was born in 1909, coincidentally the same year that Tel Aviv was founded) has left behind a cultural legacy that his son explores today. As Israel continues to define and redefine its complex identity it seems a fitting moment in the country’s history to show how both father and son have been key players in this process.

Munio Weinraub And Amos Gitai: Architecture And Film In Israel

Tel Aviv Museum of Art 27 May-5 September

[/caption]

Walking through the display of Weinraub’s architectural models and documents, including original letters of acceptance from the Bauhaus school as well as beautifully detailed plans for his worker homes, the disturbing wail of voices from Gitai’s projected work adds an almost ghostly, dissonant note to the historic and turbulent project of modern Israel.

In the past, some Israelis have dismissed Weinraub’s Bauhausinspired architecture because of its associations with austerity. With its clean and simple lines, the architecture represented the rational foundation of the state. Yet since Tel Aviv was designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2003, attitudes are changing once again.

Celebrating the city’s centenary this year, the reappropriation of the White City – thus named for its proliferation of Bauhaus-style buildings – is considered by some to be a historically revisionist project. In his book White City Black City, left-wing architect and lecturer Sharon Rotbard argues that there is more than simple praise for the Bauhaus legacy at play here.

Rotbard implies that the current focus on the White City is partly a smokescreen for the elimination of Arab heritage in Jaffa, out of which Tel Aviv originally grew. After the 1948 War of Independence many Arabs fled or were removed from the area when they were attacked by insurgents from neighbouring states. In the 1960s when Jaffa was redeveloped as an artist’s enclave its previous residents were apparently not invited to return.

Although Rotbard’s particular concerns are not represented in the show, there is much here to inform and provoke in this marvelous and exhaustive exhibition. Weinraub (who was born in 1909, coincidentally the same year that Tel Aviv was founded) has left behind a cultural legacy that his son explores today. As Israel continues to define and redefine its complex identity it seems a fitting moment in the country’s history to show how both father and son have been key players in this process.

Munio Weinraub And Amos Gitai: Architecture And Film In Israel

Tel Aviv Museum of Art 27 May-5 September