All that glisters – OMA galleries in Milan and Moscow

Garage Museum of Contemporary Art Moscow

Garage Gorky Park

While OMA has created a new art campus in Milan, the practice was also working on another new privately funded contemporary art space in Moscow, this time at the behest of Dasha Zhukova. With strong women involved and matching architectural references, there are similarities in the two projects - but the impact of the Garage in Gorky Park and the institution it houses is significantly different, says Shumi Bose

A city staking a claim for contemporary art; material mash-ups across historic and new buildings; a privately owned art institution, with a strong and glamorous woman at the helm; tantalisingly unmentioned wads of cash and shiny new buildings by OMA, with Rem Koolhaas as chief overseer. The resonances between the twin birth of new premises, for the Fondazione Prada and the Garage Museum of Contemporary Art, are loud enough that they cannot be ignored. Nor should they be, when the cocktail of feisty women, seductive architecture and a reconfigured world order heralds no less than a new chapter in the private patronage and public presentation of contemporary art.

Let's start with the architecture. In most expedient terms, OMA's architectural gesture in Moscow is exceedingly simple: a shimmering, polycarbonate box - used at this scale as a facade for the first time - wraps around the bleached concrete bones of an historic, post-war building. The existing structure inside comprises the restored remains of the Vremena Goda ('Seasons of the Year') restaurant, built in 1968 as a public canteen. In typical Russian scale, this spartan, yet monumental space, was designed to feed more than 1,200 people at a time.

So, to return to comparisons: experimental, tantalising materials? Present at both Prada and Garage. Mirrored auditoriums? Check. References to mid-century nostalgic design - or in this case, 'nostalgic', referring to the particularly bittersweet ache for Soviet-era aesthetics? Yes indeed. And an overarching rhetoric of 'preservation', of architectural confrontation between old and new? Check and check. Yet while these lists tally on paper, the embodied meaning and impact of the two buildings, and of the institutions they host, diverge in significant ways.

First, there is the budget. Admittedly incomplete at the time of going to press, the new home for Garage is clearly constructed on a relative shoestring, compared to brazenly gilded finery of the Fondazione Prada campus: the plastic facade, the minimal intervention inside, the use of deliberately basic, workaday materials. Certainly from the experience of Russian oligarchy in London and from the presumably unlimited coffers available to Garage, one might well ask: 'why so scrappy?'

In order to untangle that question, one needs to understand both the institution and the personalities behind it, including both client and architect. There are those who disdain Dasha Zhukova's position in the art world on account of her fabulous, oil-derived wealth - magnified many times over by that of her husband Roman Abramovitch, that owner of yachts and high-profile football clubs - as well as because of her youth, beauty and other things that tend to govern popularity in the playground. This view seems wilfully myopic in light of the California-raised socialite's concerted move towards art-based philanthropy, especially in her native land - where overt misogyny and political oppression remain as tangible problems.

While at night, the building services 'ghost' through the translucent cladding, like bones in an x-ray. Photo Credit: John Paul Pacelli

In 2008, having dipped into modelling, couture design and editorial work, Zhukova initiated the non-profit IRIS Foundation and the Garage CCC - at the time Moscow's biggest exhibition venue for modern art - both of which seek to advance the 'understanding and development of contemporary culture'.

One can hardly overstate the need for such support in a place like Russia, where culture has endured - some would argue continues to endure - an historic repression. At its inception, Garage occupied the Bakhmetevsky Bus Garage, designed in 1926 by constructivist architect Konstantin Melnikov. Famously, Zhukova invited Amy Winehouse to perform at the opening party.

It then went on to host exhibitions by heavyweight art-stars like Christian Marclay, Mark Rothko, James Turrell, and Marina Abramovic (no relation).

When the lease for Melnikov's bus depot ran out in 2011, Garage moved into temporary digs in Gorky Park. Again, the siting of a challenging contemporary arts institution in a highly central, public park is an intentional statement, and a bold move for the museum. The park itself, named for one of the founders of literary socialist realism - imposed as a chokehold on all Soviet artistic production for decades - was in a sorry condition after the Nineties; a regeneration programme also begun in 2011 (led by LDA, the UK firm responsible for landscaping London's 2012 Olympic Park and the development around the Battersea Power Station) has transformed it into a much-loved destination.

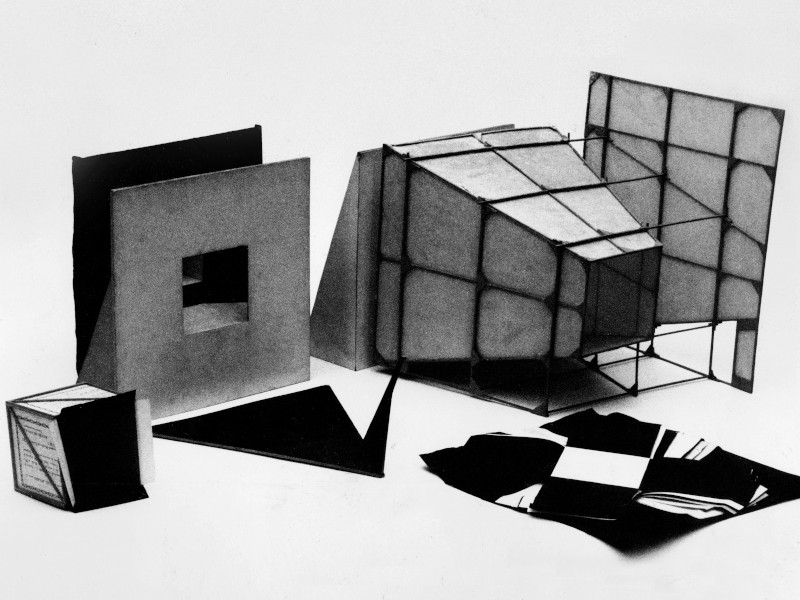

The cardboard tubes of Shigeru Ban's temporary Garage Pavilion echo the packing boxes that we all encounter, transitioning between one home and the next, while heralding the museum's permanent arrival in the park. In the meantime, Garage acquired two more historic sites in the park: the ruins of the Vremena Goda Restaurant, now the site of OMA's new building, and an adjacent site still under survey, comprising the surviving relics of the All-Russian Agricultural and Handicraft Industries Exhibition from 1923 (including Ivan Zholtovsky's Hexahedron Pavilion, one of the oldest surviving structures in the park). As with the Melnikov bus garage, the occupation of a radical but almost derelict building is already a statement: a desire to reclaim something of Russian history and identity, while imbricating itself with the cream of contemporary cultural production. The new building's rude material palette, eschewing the bling and glitz found all too easily among Moscow's elite set, is likewise an ideological move as much as a practical one.

At one point, the new building was also intended as a temporary home for Garage; as costs increased, the ethos of the project synthesised into something more to do with porosity and the invitation of everyday life into the building. Polycarbonate, concrete, tile and plywood - the 'public loop' of the gallery, between cafe, bookshop and ground floor is lined in locally sourced birch-ply - are not forbidding or imposing materials. A large area of hardscaping in concrete and cobble, combined with the dual entrances on either side of the ground level, mean that the Garage programme can spill seamlessly on to the groundplane of the park itself. Passers-by who may not ordinarily venture into an art space will, it is hoped, be enticed to pass through.

Otherwise subtle, the OMA building's most 'iconic' gesture are the 11m rising 'garage doors', operated in much the same way as that of an American suburban home. Two mechanical doors, one on either side of the building, can be raised above the silhouette of the otherwise crisp, rectilinear shed, visually signalling a public invitation to engage with what's inside. The placement of the doors, between two structural cores, also allow for a triple-height space suitable for large, specially commissioned artworks: currently these spaces house the largest paintings made in Russia, by artist EriK Bulatov.

The opalescent, mirror effect of the double-wall polycarbonate recalls the soft-polished aluminium of the Louvre Lens by SANAA, reflecting the midsummer sunset with breathtaking beauty. But the material's translucency allows for delicious, enticing games. The polycarbonate was installed in just three weeks; raised just above 2m off the ground, it forms a clean, continuous skin that betrays just enough of the inner workings, most of which are contained between a cavity wall. Mid-interview, Koolhaas jumps up to show me his favourite bit of servicing: the silhouette of which 'ghosts' through the semi-transparent plastic. A 600mm gap between the two walls allows for ventilation and heating systems and all possible servicing; gangways will also allow for workmen to inhabit the cavity while maintaining and installing all services.

The simple box volume is an unassuming, reflective shell around a protected piece of historic architecture inside. Photo Credit:: YuriPalmin, Garage Museum Of Contemporary Art

Despite its pearly allure on the outside, and following Koolhaas' current rhetoric on preservation, inside the new architecture has enough modesty to step off, letting the impressive 'floating' terrazzo staircase and concrete slab-and-post construction of the Vremena Goda speak the language of decayed, Soviet monumentality. The ground level is left largely open in plan: enclosed by a glass ribbon, it remains visually and physically accessible to the public, while special exhibitions will take place largely on the second level. The carefully enshrined crudeness of the concrete slabs contrast poetically with a large restored mosaic of 'Autumn', personified as a soaring, quasicubist woman in orange and blue, and several surfaces laid with traditional but quotidien green tiles, polished but still redolent of a time now lost. An ironic chapter in the history of Russian cultural progress is embodied on this half-new, half-old site; from grand socialist gesture in sanctioned circumstances to privately-funded artistic freedoms and cultural consumption.

In some ways, the display spaces at Garage follow in what can be called a tradition of turning former industrial architecture into spectacular caverns for contemporary art: take Tate Modern, MoMA PS1, the Hangar Bicocca, the FRAC in Dunkerque. In such spaces, curators and artists are offered a range of spaces in which to exhibit, responding to the particular conditions of the existing. At Garage, there is little in the way of the universal white-cube space common to most contemporary art spaces. A few sub-galleries around the eastern and western cores of the building offer smooth, solid walls, but elsewhere a slightly ad-hoc system of double-hinged wall-panels that can be pulled over the restored masonry and tilework as necessary.

Of course, a Sixties' building in Moscow has a special and personal resonance for Rem Koolhaas, who admits to finding his professional calling in this city. 'Soviet architecture has a scale, in terms of receiving the public, that we just don't do anymore,' he says, pensively. Koolhaas visited the city in 1965, and it was while living off Mars bars in the Brezhnev era, nourishing himself on the radical potentials of constructivist drawings, that he made the decisive transition from journalism to architecture. Before his studies at London's swinging AA, before the lurid postmodernity of Delirious New York, it was in Moscow as a young man that he realised the possibilities in architecture to 'transform and reorganise life, from the structure of the family to the city'. But at this stage in his career Koolhaas is wary - perhaps even weary - of making flashy formal gestures, preferring a complexity to emerge from the juxtaposition of old and new.

With most glamorous art-fashion-money hybrids, one might predict the obligatory presence of works by the favoured stars of the art market to dominate: a few Jeff Koons (who attended a special dinner launching the new building), for example, or Louise Bourgeois (whose work will feature in the first major show at Garage, opening in September). As consumers of freely available cultural content, we might well believe the world has enough shiny new art museums. But with a history of sanctioned expression and extreme insularity, enlightened institutions are more than necessary to introduce a broader artistic discourse, as well as to give an abundance of emergent Russian practitioners a platform to operate on a level with international peers.

Simple wood cladding wraps around the end of the rectilinear volume containing the 'public loop' & bookshop. Photo Credit: YuriPalmin, Garage Museum of Contemporary Art.

Garage recently modified its name, from Garage Center for Contemporary Culture to the Garage Museum of Contemporary Art. However, it could also be seen as a more a European model of kunsthalle, in that it does not, and does not intend to, accrue a permanent collection of artworks - commissioned works on display will remain the intellectual and material property either of the artist or their representative gallery. Garage has instead decided to focus on the collection of archives available between 1950 and 1990, specifically targeting underground and avantgarde output before Perestroika. The nominal sidestep is perhaps an attempt to gain more gravitas or weight as an institution, an act consolidated by the move to a major new architectural space - one that will be further reinforced with the development of the Gorky Park campus. OMA will continue to work on the recently acquired Pavilion, no doubt following the same course of 'modest' reinvention, and bringing yet another era of Russian history and historic architecture into institutional assemblage. Curatorial and programmatic intentions are currently confidential.

This agenda is telling in terms of the double-pronged aim of Garage as a cultural institution: one that seeks to introduce internationally renowned art to the Russian public, but also that seeks to present Russian art and culture to the world. The current exhibitions typify this dual mission. On one hand, prominent international artists continue to act as an important draw: two dazzling, immersive 'Infinity Rooms' contain the first works to be displayed in Russia by Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama, while the central exhibition foyer on the second floor is taken over by a sprawling, interactive installation from Rirkrit Tiravanija, presently adored in the Obrist-led, discursive and polyphonic garden of artistic production. Here, the brutal space is animated by persistent tick-tock of table-tennis games, played out between members of the public and the Moscow Ping Pong Club (PPCM). Players are sustained by steaming bowls of pelmeni (Russian dumplings), which are constantly prepared and doled out in an echo of the building's communal past, and clad in live-screen printed T-shirts bearing metaphysical quandaries in Cyrillic: How Soon Is Now?, What Else Is There? And the installation's eponymous statement, This is Tomorrow. It's a festival of engagement; playful, part-performance and, for a potentially unprimed public, hugely accessible.

Exhibitions & Projects Research & Education

On the other hand, the reflective output of the Garage Field Research programme occupies several of the major gallery spaces with a more native narrative, including Saving Bruce Lee: African and Arab Cinema in the Era of Soviet Cultural Diplomacy, and most interesting to a wide audience, Face to Face: The American National Pavilion in Moscow 1959/2015. Produced in collaboration with the MoAA in Berlin, Face to Face charts the impact of mid-century American art and culture had on Russia - think Charles and Ray Eames, Pepsi Cola, Jackson Pollock, Fuller domes and consumer goods - based on the titular American exhibition held in Moscow in 1959. These exchanges anticipated the famous kitchen debate between Krushchev and Nixon in a fascinating display of cross-pollination and encounter. Unfortunately it's constrained to a smaller area than it needs - such is the slightly unforgiving nature of the divisible and available gallery space.

There is also a display on Russian Cosmism, curated by acclaimed Moscow-born, New York-based artist Anton Vidokle, and centred around his film This is Cosmos! that explores the 19th-century philosophy about the future of mankind. This is juxtaposed with two displays curated by Sasha Obukhova, head of the Garage Archive Collection: Insider, which uses the documentary photographs of avant-gardist George Kiesewalter, to discuss Russia's underground art scene in the Seventies and Eighties, and (in the plywood 'public loop'), a snapshot of the attempted Family Tree of Russian Art - a long-term research initiative which seeks to map the creative networks of non-conformist art from the mid-20th century onwards.

Garage reflects not only its surrounds, but on the place of contemporary art in Russia, and the place of Russia in the art world too. Photo Credit: Yuri Palmin, Garage museum of Contemporary art

Which past to enshrine? The conflict between troubled past and present narratives brings to mind Hans Haacke's Germania Pavilion at the Venice Biennale of Art in 1993, where the artist took up the marble floor laid by the Nazi Party in 1938 and smashed it to pieces. In Moscow, the tension is not down to an unfaceable past, but one where an idea of nationhood and internationality - of unique history and nascent identity - are still in flux. At Garage, the building's mix of present and past is simultaneously more crude and confrontational than at Milan's Fondazione Prada - there is nothing elegant about the way that paint is slapped on the restored concrete, or about the material connotations of the 'plastic' facade. Yet it is also more discreet, more reverent: walls are not resurfaced, gilded, knocked through or otherwise transformed. The erstwhile canteen and its architecture was uncherished, open to the elements for decades, but now the opalescent shell, with its visible life-support systems, encases the Vremena Goda's concrete skeleton like a fetish object in a shimmering vitrine.

But from the present installations, despite their sketchy, compressed feel, the goal to expose fragile, reluctant and unknown archives, the contribution that Garage seeks to make in supporting, indeed composing, the very narrative of Russian contemporary art is clear. One hopes that private support and the sheen of international prestige can liberate the institution and the artworks it hosts to a broader and evermore engaged audience.