The Jungle Block: Marina One by Ingenhoven Architects and Gustafson Porter + Bowman

Under an equatorial sun, a new wave of Singaporean buildings is blooming with vegetation. At Marina One, a vast complex designed by Ingenhoven Architects and landscaped by Gustafson Porter + Bowman, the big innovation is to integrate a jungle into the heart of the complex

Words by Herbert Wright

In Singapore, trees sprout on the city skyline, terraces brim with vegetation, and walls vanish behind spreading leaves. It’s not as if the city has been abandoned to nature — this is deliberate. The buildings where plants have taken hold are all recent, in use and in prime condition. This is more than the emerging trend to festoon skyscrapers with plants — which has gone global, from One Central Park (2013) by Ateliers Jean Nouvel, Foster + Partners and PTW Architects in Sydney to Stefano Boeri’s Bosco Verticale (2014) in Milan. Building regulations issued by Singapore’s Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA) in 2009, aptly named LUSH, require greenery lost to downtown development to be replaced on site. Kathryn Gustafson, founding partner at landscape architecture practice Gustafson Porter + Bowman (GP+B), calls it ‘one of the most progressive urban planning laws in the world’.

Now, a new mixed-use high-rise development called Marina One, designed by Ingenhoven Architects and landscaped by GP+B, changes the game. Rather than dress the concrete jungle with greenery, it effectively integrates a tropical jungle into the very heart of a massive complex — and exceeds that requirement to replace landscape by a quarter.

Introducing vegetation to a building is more than a cosmetic exercise — it makes it greener in the sustainable sense, notably in terms of thermal performance and absorption of CO2. Ingenhoven Architects, founded by Christoph Ingenhoven in 1985, has been a key player in sustainable high-rise design since its earliest days, when ventilation was a prime ‘green’ tool and greenery hardly on the agenda. In 1991, the Dusseldorf-based practice came second to Foster + Partners in the architecture competition for a Commerzbank headquarters that radical local Green Party politician Daniel Cohn-Bendit insisted set new standards in sustainability. Nevertheless, as Foster’s design was rising over Frankfurt, so was another sustainable tower in Essen. The 127m-high RWE headquarters was the first built design by Ingenhoven, and in 1996 it beat Foster’s by mere months to become Europe’s first naturally ventilated skyscraper. Its reduced energy consumption was down to a breathing double-skin of glass.

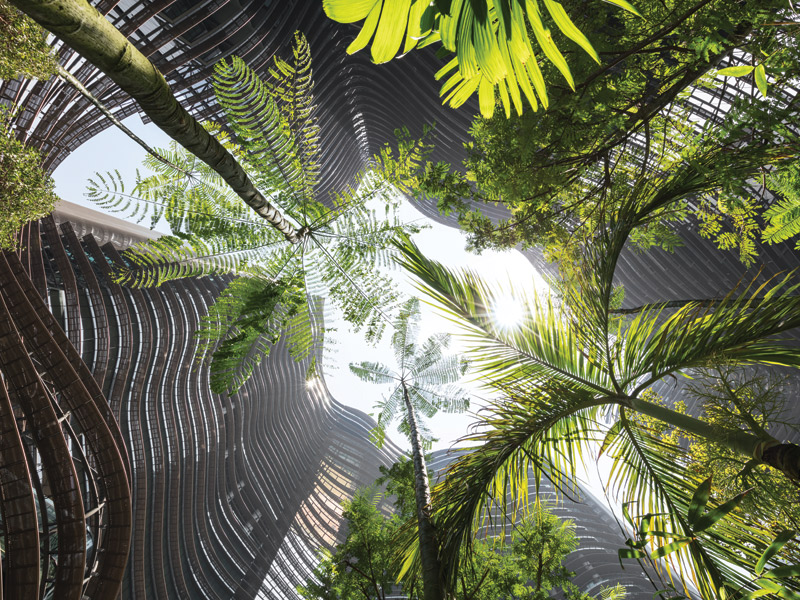

Horizontal louvres curve over the gardens of the ground floor and levels 3 and 4, then hug the contours of the office towers. Image Credit: Ingenhoven Architects / HG Esch

Horizontal louvres curve over the gardens of the ground floor and levels 3 and 4, then hug the contours of the office towers. Image Credit: Ingenhoven Architects / HG Esch

Such facades are now commonplace, but Olaf Kluge, Ingenhoven’s director in Singapore, says they are not so relevant to the tropics. ‘People don’t love fresh air here,’ he says, ‘because it’s hot and humid’. Worse, forest and peat burning in adjacent Indonesia fills the air with smoke every August. Noone wants a permeable facade then.

In 2011, Ingenhoven won the architecture competition for Marina One, and GP+B — with tropical landscaping experience from its design of Singapore’s Bay East (2009) — won the landscaping competition. But the story of the project goes back to 1965. The island state of Singapore had just separated from Malaysia, leaving some awkward arrangements. Malaysian railways crossed Singapore to its southern port area at Tanjong Pagar, on territory that remained Malaysian. It was a crazy situation, for example it gave Singaporean suspects the chance to dodge the police by simply jumping on the tracks. In 2010, Malaysia accepted a land-swap of scattered plots, to be developed jointly by Malaysia and Singapore, in exchange for the railway land.

Looking east from the oce towers, the iconic structures of Gardens by the Bay are visible. Image Credit: Ingenhoven Architects / HG Esch

Looking east from the oce towers, the iconic structures of Gardens by the Bay are visible. Image Credit: Ingenhoven Architects / HG Esch

Marina One’s plot lies on a swathe of land reclaimed from Marina Bay. It stretches from the Singapore Strait, dotted with ships outside the harbour, towards the nearby dense cluster of skyscrapers in the city’s northern financial district. Although most of the plots are yet to be developed, the location is prime and there’s already a new Metro stop there called Downtown, just a block from Marina One. The term ‘landscape replacement’ is not quite accurate here, because there was no land, but Christoph Ingenhoven knew that if there had been, it would be jungle. ‘Maybe we could restore a bit of it,’ he recalls thinking.

At first sight, Marina One looks more like a vast, massy citadel rather than a green haven. It’s so big that piling was driven 120m deep to support it. Vast stretches of glass with horizontal louvres face out on three sides, reaching a 200m-high roof level with glass service cores on the corners and outcrops up to 234m high. These are the two L-plan commercial towers, linked and together containing 175,000 sq m of office space. Below them, along the fourth side of the plot, are two further towers rising to 145m, with facades characterised by box balconies — and housing no less than 1,042 apartments. Including retail and other usages, Marina One’s gross floor area is a staggering 400,000 sq m — more than the Freedom Tower in New York and more than 15 times bigger than Ingenhoven’s original skyscraper.

That’s not a traditional waterfall beside a winding tree walk, but a cluster of 13m-long mylar strips down which water flows quietly. Image Credit: Dale Tan

That’s not a traditional waterfall beside a winding tree walk, but a cluster of 13m-long mylar strips down which water flows quietly. Image Credit: Dale Tan

So, where is all the greenery? From the outside, it can be spotted as a fringe of trees on the roofline, and plants are visible in two distinct horizontal gaps in the glass facades, but that is just a hint of its extent. To understand the scale and innovation of the landscaping, we must enter the public realm that lies between the four volumes: Marina One’s ‘Green Heart’. It is an extraordinary, tropical garden that takes root in multiple levels, through which is woven a network of looping aluminium louvre ribbons that appear to be suspended in the void, but at higher levels become snaking strips that hug the towers. The louvres extend up into the skyline. The Green Heart feels like a big-budget, sci-fi film set.

At ground level, a path runs through the gap of the mighty office towers, while a traverse road called Union Lane crosses the site, dividing the offices from the residential volumes and providing service access. They lead into a public garden, planned by Gustafson: a flowing composition which mixes vegetation with water and stone features. There are black stone reflective pools — not deep enough for water plants, and which are left fish-free to prevent fish theft — as well as a 13m-high waterfall that seems to disappear into the water (not a real waterfall, which would be noisy, but instead parallel tensioned mylar strips down which water flows). The hardsurfaced walkways incorporate gneiss stone and porto rosa granite on the central north–south path, and the benches are of polished marble.

On the Green Heart’s ground floor is a mix of hard surfaces, plantation and water pools. Image Credit: HG Esch

On the Green Heart’s ground floor is a mix of hard surfaces, plantation and water pools. Image Credit: HG Esch

Boardwalk paths spiral up through the foliage, and escalators reach level 3, which with level 4 hosts the ‘Green Valley’ skygardens in a four-storey gap in the office towers. These gardens are like a continuum with the plantings below. Higher still, at level 15, there is another realm of skygardens, the ‘Cloud Forest’, in spaces two storeys high. The skygardens lie beneath office floors, within a matrix of concrete support columns, and these gaps in the towers radically affect the air flow of the whole complex, bringing breezes into the central void. This freshens the air but brings other challenges, such as the horizontal rains that Singapore can experience, which require umbrella-like structures in places. The top layer of plantation is the ‘Mountain Top’ roof crown. Despite the Green Heart effectively occupying a well because it is surrounded by buildings, it receives plenty of light — the equatorial sun passes directly overhead like an immense heat-lamp, which is why the 33km of louvres are angled horizontally.

The jungle’s base is in the ground level’s wide 1.2m-deep beds of soil, made from excavations mixed with composted Singapore cuttings and aggregates. Henry Steed, director of ICN Design International, GP+B’s local partner, says that for the roots, ‘lateral spread is more important than depth’. In these beds, drainage is crucial — Singapore gets flooding monsoons from China as well as humid Indian monsoons. The vegetation is partially irrigated by rainwater — the entire roof runoff is harvested and stored.

Bronze-tinted steel is deployed on the undersides of solid build in the Green Heart. Image Credit: Ingenhoven Architects / HG Esch

Bronze-tinted steel is deployed on the undersides of solid build in the Green Heart. Image Credit: Ingenhoven Architects / HG Esch

From the beds emerges a range of pan-tropic vegetation from understorey plants to trees. With 42 different tree species, some of which will grow as high as 15m, 271 shrub species and a further 36 species in the green wall, the jungle feels diverse — but not quite in the way of the natural world, where biodiversity is mainly at the jungle’s edge. Nor is it abuzz with insect life, which Steed says can be good or bad. Across all levels, there are 717 trees. Even more greenery was planned, such as air-root plants for the louvres, but not everything was approved by the client.

The gardens cool the air in Marina One by 1.5°C, reduce surface temperatures from between 12°C at the centre to 23°C on the roof, filter out at least a tenth of airborne particulates, absorb CO2 and generate enough oxygen for around 550 people. But like any exercise in innovation, hard lessons are being learned as the project goes (literally) live. For example, low light levels challenge potential growth in the deepest plant beds, which lie in narrow ledges cut into the stratified granite walls of smooth cavernous openings into which escalators descend to underground car parking. The same is true in interior recesses of the skygarden levels. Over the green walls on level 4, gro-lights have had to be installed.

The contrast in facades between residential (left) and office (right), with an exterior stair core on the latter’s sid. Image Credit: Ingenhoven Architects / HG Esch

The contrast in facades between residential (left) and office (right), with an exterior stair core on the latter’s sid. Image Credit: Ingenhoven Architects / HG Esch

Despite their sheer outward facades, the forms of the 34-storey office towers are organic where they face into the Green Heart. The inside of each one’s L-plan is a waving, curving surface that recedes with height to make the blocks thinner, but above 150m bulges gently out. With similar inward curves on the residential towers, the whole central void has something of the shape of a deep bowl or vase.

Entering an office tower from the side facing the established downtown core, you ascend escalators two storeys to the double-height lobby on level 3 (Singapore uses the American floor numbering system where ground is 1). Above them hang champagne-coloured steel sculpture constellations of wavy, curly forms by Malaysian artist Grace Tan, called Planes (East Tower) and Currents (West Tower) — these are two of the five art commissions from local artists. Beside a 9m-high curtain of titanium-coated stainless steel, the West Tower lobby accesses a 300-capacity auditorium perforated with a great window.

Grace Tan’s floating sculptural installation Planes animates the level 3 reception in the East Tower. Image Credit: Ingenhoven Architects / HG Esch

Grace Tan’s floating sculptural installation Planes animates the level 3 reception in the East Tower. Image Credit: Ingenhoven Architects / HG Esch

But perhaps the best thing about the lobbies is that they open into the skygardens, which connect the towers on level 3. On level 4, where the towers are separated, the gardens extend right across the floorplate to the edges, under bronze-tinted steel ceilings. This finish reflects the vegetation and bounces light on to it. The gardens here are more formal than the jungle, with rectangular water features, and where there is solid building, it is lined with green walls. Where level 4 faces inwards, restaurant modules — futuristic glass boxes with curved edges — cantilever their corners over the jungle below. They create the thrill of being beyond a cliff edge.

Floorplates in each tower are huge, on average 4,500 sq m, but levels 28 and 29 are even larger. These are the high-density bridge floors that extend 170m right across the two volumes, and one is already occupied by Facebook. These levels can host 2,000 workers and command panoramic views from above the jungle. The bridge is a triumph of engineering, built for up to 500mm movement in wind.

It’s louvre-ly in the Green Heart garden. Image Credit: Ingenhoven Architects / HG Esch

It’s louvre-ly in the Green Heart garden. Image Credit: Ingenhoven Architects / HG Esch

The residential blocks have the same floor count as the offices but rise to just 145m, including plant. Their facades are a lot more varied, a typical apartment having a glazed, unitised curtain wall, but in a mixed field of aluminium panels and expanded mesh that creates balcony boxes protected from the elements.

A multistorey, rectangular frame composition makes the skyline look jumbled. The blocks have a clear view to the Singapore Strait, until more reclaimed land is developed. There is no high-level bridge between the residential blocks, but at level 3 they are connected by an amenity floor, housing a spa and a 50m-long pool open to the Green Heart. Porthole-like windows in the bottom of the pool cast shimmering light on to a walkway bridge below. Of all the tranquil green immersive spaces of the Green Heart, this is one of the most enchanting.

The Ingenhoven agenda has always been green — despite the violent demonstrations at Stuttgart in 2010 against its Stuttgart 21 project to rebuild the main station, because 25 trees had to be cut down for it. The new station there will be zero-energy. In Singapore, there is clearly a big tree gain, and sustainability literally reaches new heights. It should set a model for big projects in other tropical cities, which are expanding fast economically and in population, and play an evermore important role in our impact on the planet.

Behind the residential towers (foreground), the office towers are linked with a skybridge. Image Credit: Ingenhoven Architects / HG Esch

Behind the residential towers (foreground), the office towers are linked with a skybridge. Image Credit: Ingenhoven Architects / HG Esch

In an echo of Marc Augé’s supermodernity concept of bland ‘non-places’, Ingenhoven notes ‘something is still missing’ in big projects in such cities, and goes as far as to say that ‘architects can’t really generate authenticity’. But, he says, ‘they can create the long-term conditions for it’. The Green Heart he and Gustafson have created may be an artificial, high-maintenance garden, but ‘it’s not a flowerbed with white tulips in front of a hedge,’ he says. Marina One’s platinum-rated sustainability, its idyllic greenery, complexity, breathtaking drama of scale and organic geometries make it an extraordinary achievement, but Ingenhoven also expresses a hope for Marina One that is much simpler — that it ‘should bring people pleasure, they should want to spend time there’.