Review: Inside the Matrix: The Radical Designs of Ken Isaacs

Matthew Ponsford reviews Inside the Matrix: The Radical Designs of Ken Isaacs, by Susan Snodgrass

Review by Matthew Ponsford

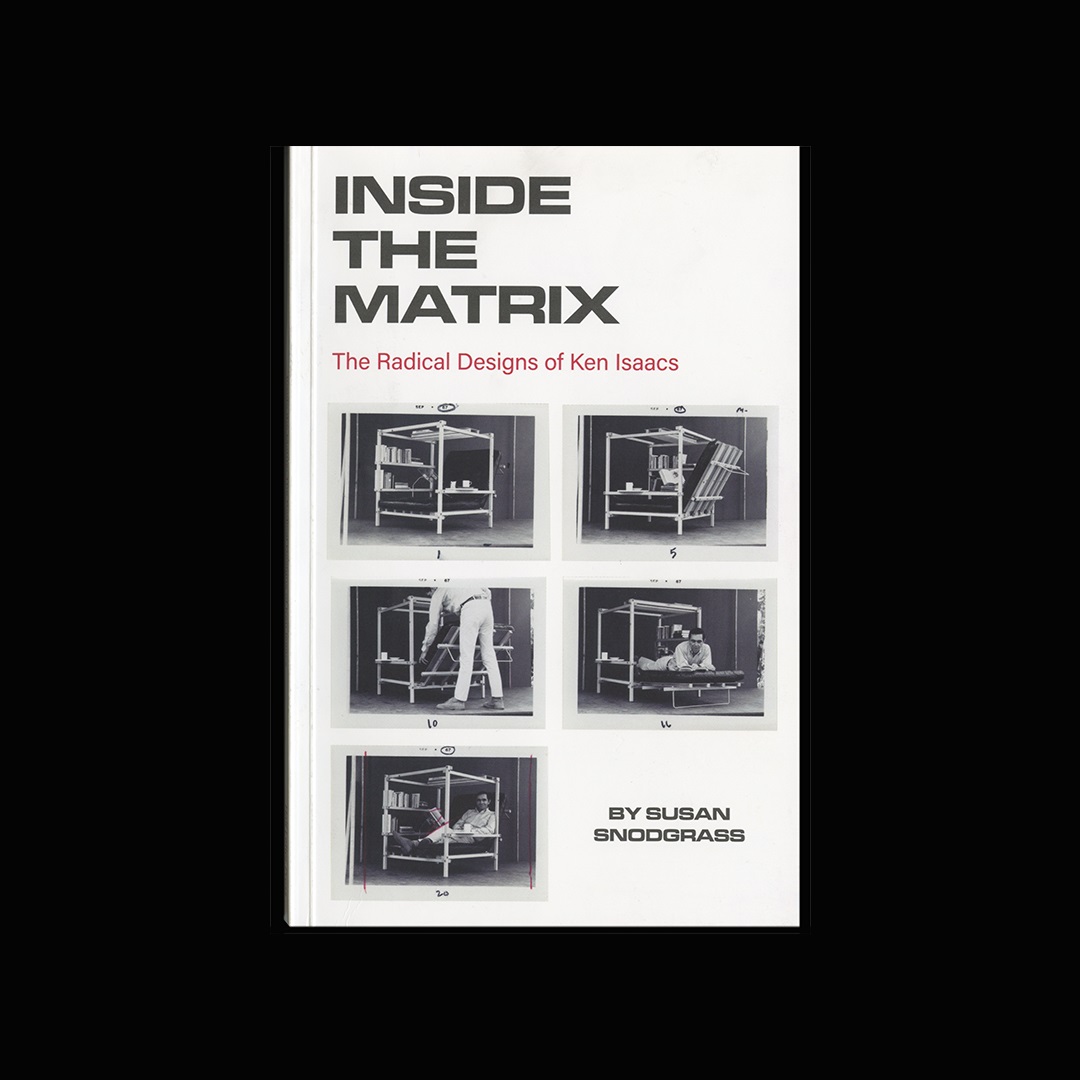

Radical designer Ken Isaacs (1927 – 2016) loved to spin a yarn. How to Build Your Own Living Structures (1974), his best-known book, is a collection of self-build instructions, personal anecdotes, and spaced-out philosophical meditations. The clarity of his structures -- self-assembly houses and multi-purpose furniture built from two-by-two beams in a Matrix grid -- could barely be further from the haphazard stories alongside them. Altogether, the guide ‘offers an intimate view of a design practice truly lived’, according to Inside the Matrix: The Radical Designs of Ken Isaacs, a new account by Chicago-based critic Susan Snodgrass.

Between the early 50s and 70s, Isaacs set himself the task of overhauling the disjointed furniture littering the postwar family home, replacing it with a system of adaptable, evolving ‘Living Structures’, like his famous 1955 Superchair. Yet, sandwiched between DIY guides to drilling and joining, his handbook offered advice on maintaining friendships and shared his befuddled learnings as a novice husband and father. His words dawdle in an endearingly digressive hippie drawl that chimes with his own meandering path from Midwestern tenant farmer, growing up during the Great Depression, gaining an education in toolmakers and military service, before architecture school.

Designing one structure, an activity station for his newborn son, he marvels at his boy's miraculous growth ‘like God is blowing up a balloon’. The finished structure is two 36-inch cubes separated with a splintery sheet of plywood with a circular hole cut in. It is an imperfect reflection of his idiosyncratic concerns -- to share an occasional meal down at his son’s table -- as much as it is a paradigm of economy and elegance. In true early 70s spirit, Isaacs concludes that the most important building process is ‘head-tooling’, his own neologism for radically rethinking the designer’s questions from the ground up.

It is odd, then, that accounts of his work tend to tease apart his minimal designs and his messy life. In spotlighting his Matrix grid system, Susan Snodgrass’ new book follows Victor Margolin’s chapter on his friend and colleague Isaacs in The Politics of the Artificial: Essays on Design and Design Studies (2002) -- the best account so far to take Isaacs seriously as an unfulfilled revolutionary of domestic design.

Snodgrass recounts how this system evolves from its first prototype in 1954, an 8-foot-tall ‘home in a cube’ designed to transform the studio apartment he shared with his wife, Jo, into a sort of two-storey house, with quarters for living, sleeping, dining and reading. The Matrix later structured Isaacs’ living furniture, some of it sold as pre-IKEA flatpack kits, and his 1960s Microhouses. Snodgrass firmly sets out to show what we can learn today, as public interest has swung back toward this strange moment of DIY, eco-focused, counter-cultural, nomadic idealism, roughly marking the intertidal-zone (from the 1960s to the 70s) between modernism and postmodernism.

Snodgrass is best when describing this intellectual flux and how Isaac’s autodidactic simplicity cut a path across the modernists. He arrived as a student at Cranbook Academy in 1952, a decade after its heyday, when founding director Eileel Saarinenen taught Florence Knoll and the Eameses (as well as his own son Eero). Isaacs learned ‘simplicity’ from his homesteading parents and considered the modernists’ furniture a phony success: a kind of “visual cleaning-up of existing artifacts” that encouraged further wasteful cycles of consumerist accumulation.

Isaacs' provocative structures were celebrated in mass-market magazines like Life and, from 1968, he published build-at-home instructions in Popular Science magazine. By the early 70s, the world had caught up with Isaacs and his How To guides were self-published alongside Whole Earth Catalog (1968-72) and Ant Farm’s Inflatocoobook (1971).

Snodgrass biggest achievement is to create a portal to a world which shared contemporary concerns with living light on the land, dematerialising, degrowth, and open-sourcing. Sometimes, though, straight lines are drawn where wonkier ones belong, such as from Isaacs’ Microhomes to the post-2008 vogue for tiny houses. Microhouses were ‘culture breakers’ designed to ‘beat the system’ by supporting a freewheeling nomadic existence. Isaacs himself resisted cultural parallels in interviews in the years before his death in 2016: tiny houses are more like the old-style home Isaacs damns ‘a pathetic replica of the palace’, reflecting residents’ ever more desperate position trapped inside the system he hated.

Following Isaacs’ career is a joy but Snodgrass avoids getting intimate -- a shame for such an engaging subject. Snodgrass expounds the dialectic between his personal experience and design philosophy, but rarely offers much detail on the personal, leaving the reader to look longingly at the book's beautiful colour photographs of Isaacs family, who look like they’re whose lives loom large against the backdrop of the matrix grid.

Cutting away Isaacs' messy, fun emotional being to leave the sensible Matrix System also ends up at odds with Snodgrass’ goal of excavating what he shows us that is relevant today. Isaacs urged designers to learn from his processes of head-tooling, not necessarily his precise design methods. ‘It sounds olympian, but the real worth of that stuff is some young person picking up on it and causing them to do something -- but not that thing!” said Isaacs in an interview with Dwell in 2008. “It can be something else. And that’s what’s important to me.’