Profile: Victoria Broackes, director of the London Design Biennale

Victoria Broackes, director of the London Design Biennale, on the importance of design

Words by Sophie Tolhurst

Speaking to Victoria Broackes over Zoom, I can see a map covered in pins on the wall of her office, and all around it different images of pavilions for the London Design Biennale (LDB), the international design event that Broackes is currently director of. But they aren’t images of this year’s pavilions, she admits. ‘We haven’t got any time to redecorate my wall at the moment,’ she says, laughing. ‘We’ll have to go with the ones we’ve had up for a while.’

With the interview taking place just before the biennale opened (it ran 1–27 June), Broackes is, naturally, rather busy. She’s at the helm of an event that needs a lot of coordination and communication any given year, let alone the current one, with Covid-19’s constantly shifting boundaries and varying restrictions – different, of course, in each country. Despite these issues, it is coming together. ‘People have been absolutely amazing, [and] the countries have been amazing about working through those things,’ Broackes says. ‘Along with everything else, the countries, cities and territories need a pat on the back for being able to do this at all.’

Broackes is a curator by training. She studied the History of Design course at the Royal College of Art, London, before starting her curation career as a freelance researcher in the 20th Century Design gallery at the V&A. That gallery was what had been the Boilerhouse Gallery, run by Terence Conran’s team as a temporary project in a basement of the V&A – later evolving to become the Design Museum at Shad Thames (before its Kensington relocation in 2016). It was an exciting place for a young curator, where projects included working with influential graphic designer Neville Brody (around the time of The Face magazine), and where they could experiment with ‘theatrical’ displays for exhibitions, such as one on fashion and surrealism. ‘We were doing fun, different exhibitions; we thought we were doing the coolest exhibitions in London,’ Broackes says, adding, ‘[but] probably lots of other people thought that too.’

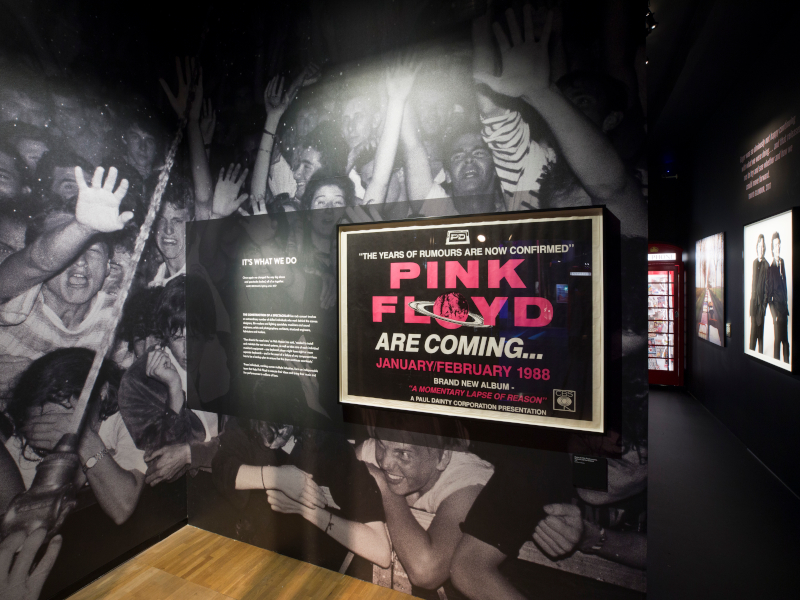

After having children, Broackes returned to the V&A, moving ‘almost by accident’ to the theatre and performance department (then the Theatre Museum in Covent Garden). Broackes has since worked on ‘Kylie: The Exhibition’ (2007), ‘The Story of The Supremes’ (2008), ‘The House of Annie Lennox’ (2011–12), ‘David Bowie is’ (2013), ‘You Say You Want a Revolution? Records and Rebels, 1966–70’ (2016–17) and ‘Pink Floyd, Their Mortal Remains’ (2017). ‘David Bowie is’ was then the most visited touring exhibition the V&A ever had, receiving more than two million visitors by 2018.

The V&A is uniquely well-positioned to do these shows, Broackes explains, having had the foresight to collect items from music and performance since the 1960s. Collected with a design lens, there are items like posters by Hapshash and the Coloured Coat, garments from influential 60s boutique Granny Takes a Trip, or particular costumes worn by musicians. These music-related objects had been ‘underused’, however, until Broackes saw the opportunity to use it as material for exhibitions.

Broackes sees music as the art form that people can relate most directly with, in contrast to art and design, about which, she explains, ‘people are quite nervous. They think they have to be highly educated to take part in [it]. Which I always think is a great shame, because, of course, it’s actually not true.’ With music, though, ‘people just sort of get it… it really couldn’t be better as a way of engaging with heart and soul and the brain.’

Broackes is director of London Design Biennale, following on from her role as head of the London Design Festival at the V&A

Broackes has also been able to take this understanding of visitor engagement to the other side of what she does at the V&A: the London Design Festival, which she worked on from 2008 to 2019. She describes that work as having been ‘really, really fun’: a refreshing change to the long lead times and meticulous plans usually required by exhibitions in a large museum. ‘If you are doing an exhibition, it’s two years minimum – probably more. To be working on something like a festival, where it might be two months... [it’s] a whole different dimension and I enjoyed that – the energy of it and the immediacy, and the feeling that it very much speaks of the moment.’

Another source of excitement was the chance to place new temporary interventions in and around the V&A’s storied collection and building, but this was an unexpected bonus when the festival was first being set up. ‘The first year I did it I was looking for empty galleries – which isn’t a thing that is easy to find – and because there weren’t any, that’s why we started to use the galleries [that were] full of things already, and then realised that was really the point. That was where the energy and excitement was coming from.’ Such juxtapositions can be productive, Broackes believes.

Ini Archibong’s Pavilion of the African Diaspora, shown at this year’s biennale. Image Credit: ED REEVE

Returning to the present, and to LDB 2021, Broackes tells me one of the aspects she was most looking forward to is Forest for Change, by the biennale’s artistic director Es Devlin. With 400 trees dropped into the courtyard of Somerset House, it broke an 18th Century rule against planting trees in the space. ‘You’ve got Somerset House, a very age-of- Enlightenment building, telling you that Man is the measure of all things, and then you’ve got a forest saying, “Actually that’s no longer the case... we now know we have to live in harmony with nature or we’re in serious trouble.” The forest will educate people about the UN sustainability goals, but it will also be somewhere for visitors to enjoy the scents of the forest and birdsong – from a soundtrack recorded by Brian Eno – as they wander through.’

On the institution’s other, river-facing side was the Pavilion of the African Diaspora, by designer Ini Archibong. This was another highlight for Broackes. ‘It’s such a good and important thing to have a pavilion that speaks not just to one aspect of the diaspora, but speaks to the voices of many, and this is very much a participative and performative space that will and can be used in lots of different ways – and we’re very fortunate to have that up there.’

Ross Lovegrove’s Transmission, from 2017’s London Design Festival, which Broackes curated. Image Credit: VICTORIA AND ALBERT MUSEUM, LONDON

Other highlights for Broackes had environmental issues at their core: from the Polish pavilion, which looked at the efficient use of fabrics in Polish architecture to keep cool in summer and warm in winter, to the Canadian pavilion, which forced visitors to walk around a very large ‘but rather beautiful air conditioning unit, in order to say, “Look, notice this, we are forcing ourselves to build this into our buildings; things that we may not need if we built better and in different ways.”’

From the 2013 exhibition ‘David Bowie is’ at the V&A, its most popular ever show. Image Credit: VICTORIA AND ALBERT MUSEUM, LONDON

And while there were fewer pavilions than in past years – 30 rather than 45 – that meant new opportunities could be found in the gaps: universities and art colleges were invited to participate, while Broackes curated an additional exhibition called ‘Design in an Age of Crisis’. Set up in partnership with think tank Chatham House, its global open call invited a wider audience to enter a conversation on design in response to the critical issues of the present, attracting 500 submissions from over 50 countries across six continents. Its conceit was to give radical design ideas the platform to influence spheres beyond the design sector, in areas such as policy or academia. The idea that design has something to offer policy makers, Broackes explains, has been a part of her design outlook since her days at the Royal College of Art, where her professor Christopher Frayling believed that ‘the conversations about design weren’t necessarily happening in the right places’.

Covid may have provided plenty of challenges in the running of this year’s LDB, but Broackes feels there is the potential for it to have left a lasting impact. ‘This is a sort of watershed moment. I’m excited by the level of participation in something like Design in an Age of Crisis. In having those conversations, I think design has a really important role to play when we’re looking at things like social inequality, environmentalism and the very big issues of the moment.’