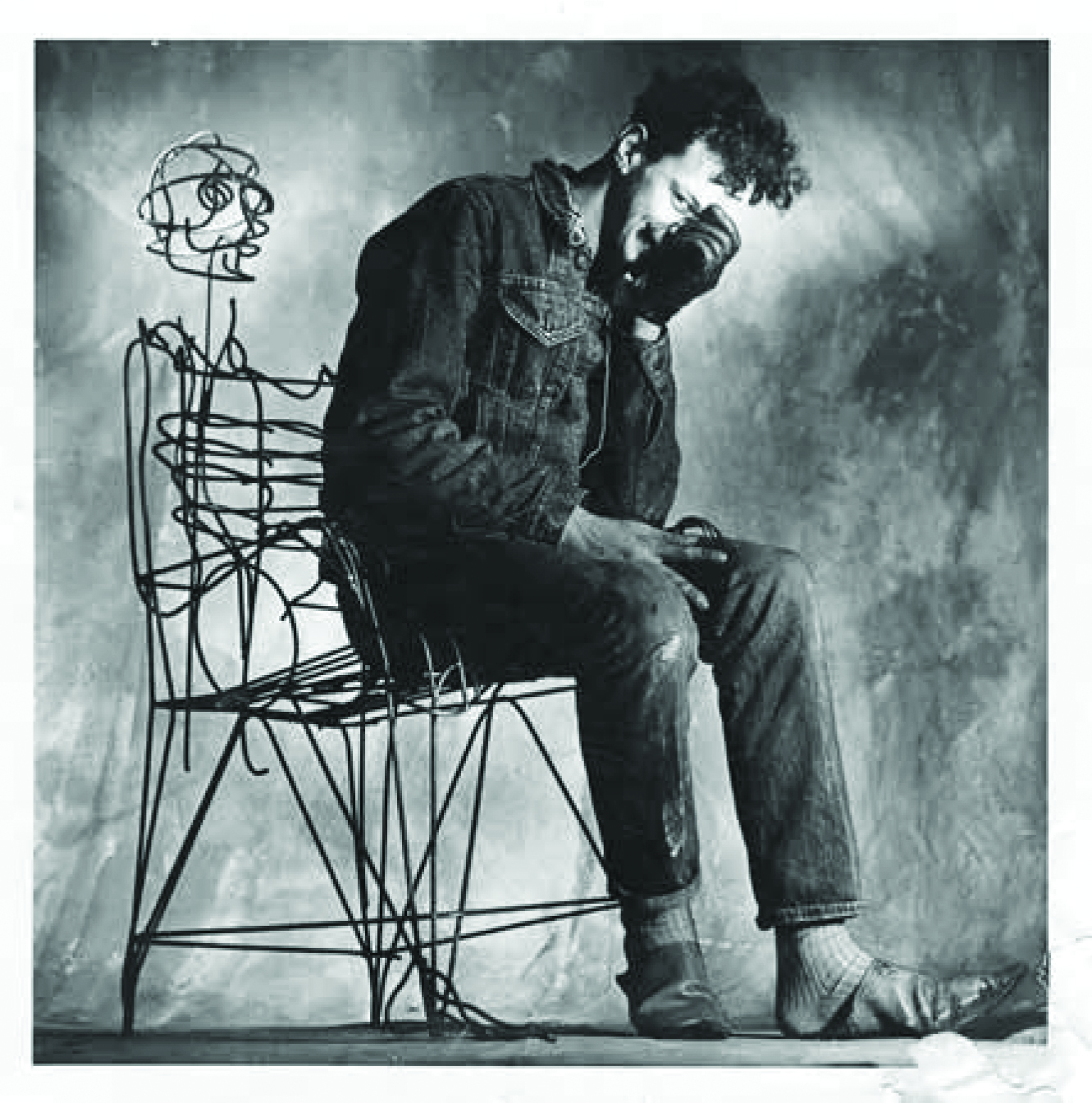

Profile: Tom Dixon

The road less travelled — From metal-bashing artist to design doyen, Tom Dixon has taken a unique path through the design industry, that has included everything from playing in a band and running nightclubs, to being the creative head of high-street design stalwart Habitat

Tom Dixon’s design career has two very dramatic defining moments: two motorcycle crashes, both ending in broken limbs. The first happened when he was part way through a foundation course. He’d left school with one pottery A-level and still wasn’t enjoying the regimented learning life. After recovering from a broken leg — two weeks in hospital — he never went back to education, instead deciding to journey down a road that has led to now, albeit circuitously and serendipitously. ‘That was fortuitous, I think,’ he reminisces as we tuck into a sharing plate at his Coal Office restaurant in King’s Cross.

The second bike smash happened just a few years later, when he was the bass player in a band called Funkapolitan, which had signed to a major label and seen action supporting the likes of The Clash and Simple Minds. He broke his arm a week before the band was due to tour. They replaced him and… he never went back. It’s a pattern of dramatic change and seeking out new and personally meaningful opportunities, that is a hallmark of the unique route Dixon has taken through the design industry, to become the leading figure he now is.

When Blueprint decided to do a materials issue, it seemed like the perfect opportunity to profile Dixon. Materiality is an important part of his work. Among other things, he’s single-handedly made brass a current staple of interiors and a glance around his Coal Office showroom-cum-office-cum-restaurant, reveals glass, cork, raffia, marble, terrazzo, copper, resin and plenty of metal — his first love. But in actuality, while materials are a vital part of his work, what emerges in a lengthy chat with him is that he has been very process driven, very hands on and always looking around for the next thing — even if this latter part was more down to his personality than any real career intent.

Our conversation goes on a chronological journey of how he arrived at this current point in his ‘career’, through a scattergun set of circumstances. So, to pick up the story after the first crash: ‘I went out and got the first job I saw advertised,’ he says, which was as a technician in the machine shop at Chelsea School of Art, where he got to use the equipment when the students weren’t around. From there, aged 21, he went to a printer’s, where he learned about offset lithography while cleaning the machines, before going on to hand-colour animation film frames in Soho.

It was around this time in the London post-punk scene, that the band he was in started getting serious attention: ‘I learnt — in terms of communication, making posters, doing branding, doing record sleeves, creating our identity as a group of people. It’s entrepreneurial being in a band. It’s your own expression, it’s your own business so you make money from it and organise yourself as a band of vaguely like-minded individuals to kind of sell your creativity.’

Then the band was signed by PolyGram: ‘So the other part of the music analogy is, we get bought by a company, which is sort of what has happened to me now in a way, because I’m now owned by private equity. It goes from being really fun, self-propelled and amazing, because we were playing at the roller disco in Hammersmith, The Wimpy Bar in Notting Hill Gate and the Royal College of Art — then as soon as you sign a record deal you’re suddenly in a machine. We go from being the kings of west London to the losers that were supporting Simple Minds in Helsinki or Ziggy Marley in the south of France, or The Clash in New York — in principle amazing, but the reality is, we’re disco and then we’re put in a reggae context or a rock context or a punk context. They threw bottles at us.’

The seeds of discontent were clearly there and the second bike smash meant a new path: nightclubs, with some like-minded individuals. The clubbing weekenders saw him making enough money to be free during the week and he took to welding — a natural extension of his motorbike and car tinkering. ‘The nightclubs ended up again being quite an entrepreneurial business,’ he recalls, ‘which put me in touch with a lot of people that were in different types of creativity in London at the time — the fashion people, Katharine Hamnett, Vivienne Westwood, or all the hairdressers, the photographers… I think the advantage of the club business is you end up with a vast network of people and when I started making things, they became my natural clientele, because everybody needed a theatre set or a shop window, or racking for their shops.

‘I’d done woodwork at Chelsea School of Art, but it requires a lot of planning, a lot of waiting for glue to dry. Metal — welding — gave me the ability to speed up. Maybe I’m borderline ADHD, I get bored so easily, so it suited my impatience, basically. It suddenly became a thing — the fire and the melting metal — the ability to make big or small structures quickly and then rip them apart and remake them and make things that people would then buy. It went really very quickly from hobby to profession, because people wanted the stuff and I still don’t really know why, because they were ugly, they were brutal, they were dangerous and they were misformed, but they just weren’t like anything else that people were doing at the time I guess.’

.jpg)

The early Eighties saw him scouring London’s scrap metal yards and turning out his art/design objets with, as he puts it, ‘no real intent to be a designer’. He was just doing his own thing and, in the process, building up his own metalwork business, which saw the likes of Thomas Heatherwick, Michael Young and Michael Anastassiades put in stints early in their design lives.

That rampant decade saw him hone his skills, bring in new tools and start to concentrate more on refining forms. In 1989 he created the S-Chair — a long way removed from his earlier ‘brutal’ constructions — and with it, came the attention of the Italian furniture industry. ‘I got better at welding and I moved away from using just found objects,’ says Dixon. ‘I picked up a couple of tools and started understanding metal work a bit better. I was making more and more things that had to function. Initially I hadn’t cared if the thing was sharp or dangerous, but when you were in a hairdressing salon or in a fashion store, you had to kind of round off the edges.

‘The things were decorative, not because I was naturally baroque — they were that way because of the nature of the objects that I picked up. I got better at putting them together and getting a sense of proportion, a sense of functionality.’ One of the most forward-looking of Italian furniture manufacturers, Giulio Cappellini, visited him while he was showing at a gallery in Milan: ‘Cappellini was always a bit of an odd ball. He said you should put one of these chairs into production. Then he used to pass by the studio and just wander round it and say, “Let’s do that one.” The S-Chair wasn’t designed for Cappellini, but, of course, it was kind of amazing seeing something done by Italian craftsmen, these people knew how to do it better than I did.

‘I hadn’t really been exposed to a lot of proper design or global distribution or proper manufacturing actually because we were making it up as we went along. We didn’t really know about the real furniture business. The collaboration with Cappellini was kind of joyful because these are family companies. I’d always been very keen on Italy, and Italians just generally, and there was something that felt like a homecoming almost — about being in a place where they recognised you as a designer and also as a person that could add value to what they did. They all had an opinion, from the metalworker to the grandma of Cappellini. It was discussed and celebrated in a way that just didn’t exist in the UK.’

That said, working for multiple brands in the way, say, contemporary design icons like Philippe Starck were doing at the time, wasn’t to prove to be the way forward for Dixon. Royalties take a while to come through and he had a workshop to feed. He says he just wasn’t cut out for this role: ‘I wasn’t particularly prolific in that way. I couldn’t design to a brief really, and I still can’t very much!’

During the Nineties, he did work with other brands, but also moved his own work forward, branching out in to lighting and using different materials, in particular with his polypropylene Jack Lights. Then, towards the end of the decade, something dramatic happened: not another bike crash, but something that looked like an extremely dramatic U-turn nonetheless. He went from being a maverick artist/maker/designer to joining IKEA-owned Habitat as head of design. He had in the meanwhile also set up another company, Space.

‘I was a serial entrepreneur,’ says Dixon, ‘but I had no idea about the basics of finance, marketing, HR, all the stuff you need to be quite good at. Then there was one point where we were doing some metal work for a nightclub in the west end and the client didn’t pay and it was a big bill. I started feeling really shaky at that point and by then I was a father. I had a friend who was just leaving Habitat who had a kind of product developer role and said, “You should go in and see these people, my job’s going.” I was interested in change so I went to see them and there was a bigger, better job available.’

Dixon joined Habitat in 1998 in what, at the time, appeared like a very incongruous move for both parties. I ask whether he wanted a safety net given his Space experience and familial situation. He bristles: ‘No, it was a really risky move in terms of integrity. A lot of people were saying you don’t want to go and work for a corporation. It’s not you, you can’t do it. Some people were super negative about it, but for me, I was feeling, wouldn’t it be nice to not have all of this, not have to deal with a load of greasy workers and machines and oxyacetylene bottles and insurance. It had become a kind of burden rather than what it was before, which was a joy to make things.’

Talking about his Habitat time now, you understand it was an essential move along the path to setting up his current eponymous company. But his initial expectation of going in as a designer was quickly thwarted: the role was much more managerial than that. He found himself looking after a design team and the massive churn of retail items that required constantly refreshing and updating. Dixon threw himself into this steep learning curve (no motorbike involved): ‘I was learning about SKUs, learning about shipping containers, and really going around the world inspecting manufacturing and getting knowledge in umpteen domestic categories from art prints to flowers, toys and Christmas decorations, textiles to tableware. For me it was like an Aladdin’s cave of possibilities, it was so abundant in possibilities. It was an amazing way to learn about what people really buy rather than what you think they buy.’

Dixon was at Habitat for a decade in varying roles. He says he also used that time to ‘teach myself properly about design’. He created the Living Legends range with the likes of Achille Castiglioni (see page 196) and Ettore Sottsass, commissioned pieces for the store such as the Simon Pengelly-designed Radius range of furniture, which has been one of the store’s biggest sellers and even, on the 40th anniversary of Habitat, went out and commissioned a raft of products from unlikely sources including Daft Punk (a disco table) and Buzz Aldrin (a moon light). Conversations with Mikhail Gorbachev and Imelda Marcos, perhaps luckily, came to nought.

And of course, we can’t talk about Habitat without drawing design and entrepreneurial (and even restaurateur) parallels between its founder, Terence Conran, and Dixon. They have both sought their own particular ways to bring design to the fore. ‘Terence wasn’t just doing a design brand with Habitat,’ says Dixon. ‘That’s what was misunderstood. He was kind of a merchant, bringing the best of the world in.’

Dixon clearly enjoyed his time on the high street, but returning to the idea of not being the holder of your own destiny, adds: ‘Habitat should never really have been in the grip of IKEA, which was like a really successful older brother that you always felt slightly inferior to, because you didn’t make any money.’

He set up Tom Dixon in 2002 while still on the board of Habitat and quickly managed to grow it to a million pound business, through a mixture of wholesale and interiors, before attracting investment from a company called Proventus. This was done on the proviso that Dixon also manage the £20m Finnish furniture business Artek in a ‘reverse takeover’. Artek was sold to Vitra after half a decade. ‘Eventually we were happy to see Artek float off into a golden future, while we concentrated on our thing — and now more recently we’ve been bought up by another private equity company [Neo in 2015],’ he says with that same air, or ruefulness, that appeared at the beginning of the conversation when we were talking about Funkapolitan signing to a major label.

Are those feet beginning to itch a little again? In any case he’s certainly got plenty of new moves afoot. Dixon moved his operation from Ladbroke Grove to King’s Cross in 2018 and more recently added restaurants to his empire. Last year, instead of a show during Milan’s design week, he opened the permanent restaurant The Manzoni on Via Manzoni. Again, the parallels with Conran spring to mind, but the Coal Office and The Manzoni are not really stand-alone eateries, they are holistically part of the brand — and are used to road test new products such as the FAT dining chair which appeared in the Coal Office last year for eight months before going into full production. ‘I think of it as an early warning system that also allows us to have confidence in our things,’ Dixon says. ‘It becomes a laboratory — a way of testing our decoration ideas.’

Tom Dixon is now big business and 2,000 people a week pass through the doors of his deeply characterful industrial premises in Coal Drops Yard — fittingly, in what used to be an old nightclub. The company now has a broad and ‘almost complete’ range of products from furniture and lighting, through to interior accessories and fragrances (something he thought he’d never do until he realised how much smell affects the perception of an interior) and Tom Dixon can be bought in more than 90 countries around the world. And of course, there is the interior design side of the business — Design Research Studio — spanning everything from residential, through hospitality and retail, to corporate spaces including architecture.

So, having reached the here and now in the Tom Dixon journey, I finally turn my attention back to materials: ‘You must come and see the cork furniture we’re launching in Milan [the cancelled 2020 event],’ he says, jumping up and heading for the stairs. But we never make it there, because by the time we reach the showroom, he’s moved on to something new that has captured his attention and imagination.