Process – The making of Wolfgang Buttress’ UK Pavilion

By Cate St Hill

For the Milan Expo this year, artist Wolfgang Buttress has created a multimedia Hive inspired by the British Bumblebee. Cate St Hill met manufacturer Stage One at its workshop in Yorkshire before the complex structure was taken to Milan.

In the depths of rural North Yorkshire, unbeknown to many, a team of some 100 people have been beavering away creating this year's UK Pavilion for the Milan Expo 2015. Here, three aircraft hangars are home to Stage One, the design and engineering company that has helped bring to life some of the greatest feats of design in recent years, from multiple Serpentine Pavilions to Heatherwick Studio's kinetic Olympic cauldron.

Since September it has been piecing together the complex jigsaw puzzle that is Wolfgang Buttress' pavilion -- a beehive-inspired, 14m cuboid lattice that looks on to a 40m-long meadow and orchard. It's the result of five months of intense on-site build and an overall design process that started before Buttress' competition entry was even chosen. (Rather unusually for such a project, Stage One undertook the contract to build the pavilion without setting eyes on the designs and was invited to help choose the winning scheme from the shortlist of entries.)

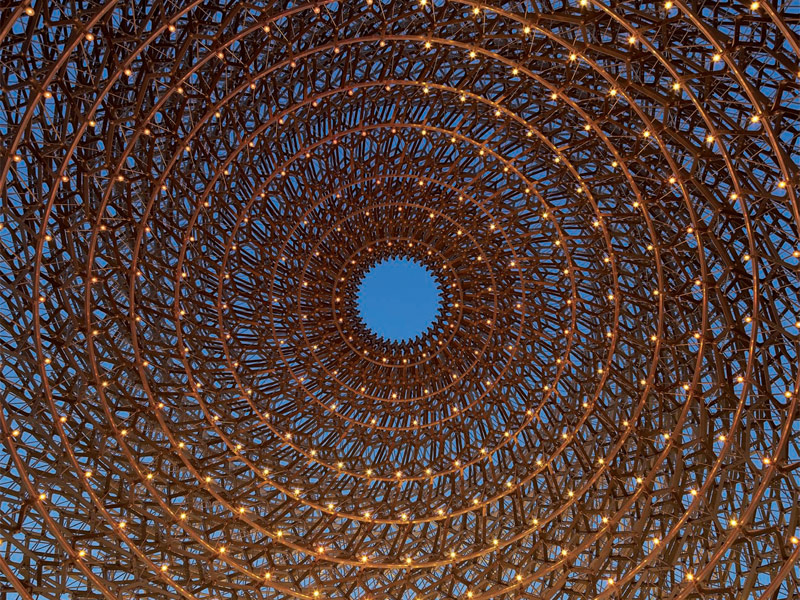

'We're very keen to say we're makers, we're good at complex -- innovation runs through everything we do,' says Stage One's sales and marketing director, Tim Leigh. 'We undertake projects without knowing at the start how on earth we're going to achieve them. We like working with young, ambitious practices that come up with hare-brained schemes; we learn from them and they learn from us.' The Hive, of 32 layers and 115,000 aluminium components, is effectively a 'giant Meccano set' that has been bolted together on site.

More than 30,000 nodes connect the cuboid lattice of the Hive. Photo: stage one

'We came up with a very clever way of taking the design and making sure it could be built on site without any welding. There was always quite a nice creative bashing of heads in terms of how Wolfgang saw the pavilion coming together and how we anticipated it working.

Each part is numbered ready for loading. Photo: stage one

Working in an environment which has 160-odd countries present means that it's a very busy site. Although we're used to working on sites with lots of overlay, such as the Olympic Park and so forth, it's tricky. Is it similar in construction terms to anything else we've done? No, absolutely not.'

The Hive is effectively a 'giant Meccano set' made up of 32 layers. Photo: Cate St Hill

Work started on site in Milan in November. The first task was to prepare the site, removing 300 tonnes of water and replacing it with 200 tonnes of aggregate. 'When you think of Milan, it's sunny and great, but actually during the winter it's not really, it's grim. What you've got to remember is that this Hive is pretty heavy, it's about 50 tonnes, so we had to make sure that the groundwork was in good order.'

The parts were transported to Milan as individual components and assembled on site. Photo: stage one

Then the steelwork went in for the 'accommodation block' behind the Hive that features an auditorium space for conferences and one-off events. Meanwhile, back in Tockwith, Yorkshire, fabrication was well under way for the various parts, from mirrored, louvred panels that form the perimeter of the pavilion to the 30,000 nodes that bolt the Hive together.

The spacers that connect the nodes. Photo: stage one

Each layer of the Hive has different lengths of rod and cords, which all required different manufacturing techniques, to form a 9m-wide spherical void for visitors to enter in the centre. The parts were transported to Milan as individual components, each numbered to describe exactly where they should be positioned. 'You can have two different nodes that essentially look the same, the only thing that differentiates them is their number.

Milling the nodes. Photo: stage one

Given that there are 115,000 pieces it was really important the truck got there and we didn't find a piece missing!' says Leigh. Once inside the pavilion, there's more than 1,000 LEDs that 'buzz and pulsate' -- they're activated by accelerometers that monitor vibrational activity of bees in real UK beehives, part of research work by Dr Martin Bencsik at Nottingham Trent University.

Paths and routes weave through the meadow to the Hive. Photo: Hufton+Crow

The last thing to go in was the orchard of British fruit trees and the meadow planted with native British floral species. Paths and routes, referencing the 'bee's dance', run through the meadow leading to the Hive, itself raised to create a sheltered area underneath for visitors to pause in. 'The idea is that the visitor is at a bee's eye level within the meadow so it really feels like they're in among it, so that it's not just one of many pavilions,' says Leigh.