Light + Tech

Jill Entwistle takes us through some of last year’s award-winning lighting installations.

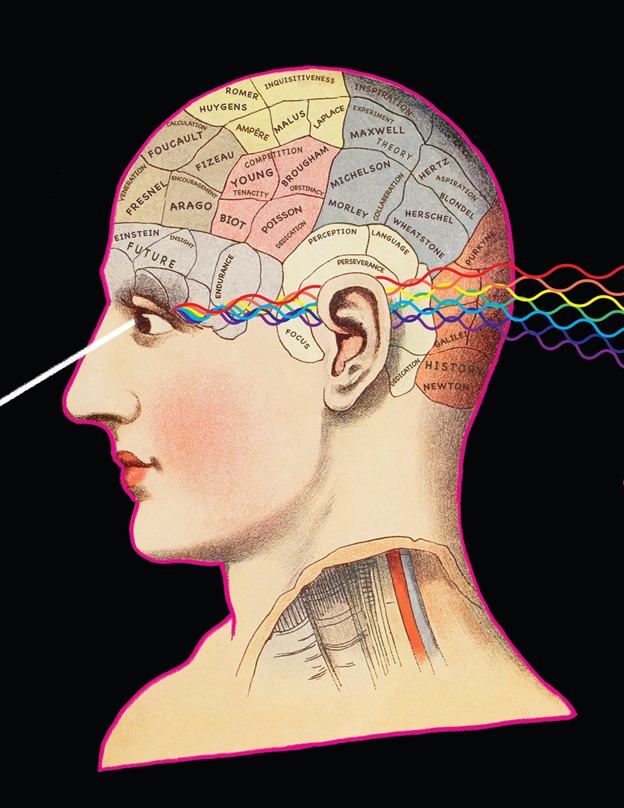

‘IS THERE ANYONE who doesn’t love a rainbow?’ asks Michael Grubb. ‘As a lighting designer, rainbows seem to me to encompass everything about light: science, magic, art, joy.’ That’s why these natural phenomena are the starting point for Stories with Light, written with Francis Pearce and published to celebrate Michael Grubb Studio’s 10th anniversary.

The quest to capture and master light has led to numerous inventions and bright ideas from some of history’s leading thinkers

‘As the title implies, it’s a collection of stories and facts that aims to cover at least part of that spectrum but not in an academic or technical way and not as a “how to” book, either,’ he explains. ‘The hope is that the characters, incidents and ideas about light we’ve uncovered will give readers a new appreciation of the connections we all have with natural and artificial light. People have been wondering about light, how it works, what it is, how best to make use of it, for as long as they’ve been asking questions – but we’re also amazingly complacent about it.’

Light serves as a foundational experience not just for humans, but even for animals who operate either diurnally or nocturnally

The stories range from the crafty and sometimes fatal reactions of the French, early forms of street lighting and Isaac Newton’s chilling self-experiments (probing the nature of colour, he stuck a bodkin in his eye socket) and the pilot whose life was saved by bioluminescence. Real-life characters in the book include William Murdoch, who is credited with inventing gas lighting and developed a kind of bagpipes-blow torch hybrid to light his way across the Cornish countryside; the humble and unsung Scottish inventor of electric lighting, James Bowman Lindsay; and Iraqi Arab medieval polymath Ibn al-Haytham (Latinised as Alhazen), who wrote the most important book on light in history more than 1,000 years ago while in hiding from the ‘Mad Caliph’ of Fatimid Cairo.

Until relatively recently attempts to understand light mainly centred on vision, but as Rudolf Arheim wrote in Art and Visual Perception, ‘light is more than just the physical cause of what we see. Even psychologically it remains one of the most fundamental and powerful of human experiences.’

In the past few decades, we’ve found out much more about perception, learnt a great deal about what light does to and with our bodies, and we’re beginning to discover what this might mean for our health and wellbeing. Added to this, new technologies are being developed that take the use of light beyond illumination into areas of medicine, computing and communications.

Stories with Light also looks at some bizarre ideas such as extramission, the oddly persistent belief that light issues from the eye, and puzzles such as the strange case of Patient M, who was shot through the head and as a result saw the world upside down. Then there’s the scientist who grew eyes on the legs of a fly and the man who made music with street lamps.

Although it’s intended as a light read, the book also makes a serious point by emphasising the value of darkness and its role in our evolution.

Wembley Stadium’s changing rooms were given a light design that encourages teamwork, energy, diversity and, if the happy need arises, celebration. Image Credit: Wembley Changing Rooms: Tom Bird Photography

When we began to control light, it was through firelight or the dim glow of a rudimentary oil lamp, technologies that may even pre-date homo sapiens, but certainly arrived long before the window, our earliest means of manipulating natural light.

But, in the space of just four human lifetimes, we’ve come to experience thousands of times more lighting in our daily and nightly lives than any of our ancestors.

Around 250 years ago, the Great Illumination brought an astonishing increase in our consumption of ‘artificial’ light. Roger Fouquet and Peter Pearson of Imperial College, London, calculated that by the year 2000 total lighting consumption in the UK was 25,000 times higher than in 1800. Put another way, we were using 2.5 million percent more light.

The Chimney Lift visitor experience at the newly regenerated Battersea Power Station. Image Credit: Battersea Power Station: Ralph Appelbaum Associates/ Andrew Lee

It wasn’t until after the First World War that electric lighting began to dominate, largely because governments of every stripe pushed for greater use of energy. The more resources we could burn up, the better, they said, because using energy promoted economic growth, increased productivity and boosted consumption.

Efforts to promote and exploit new lighting technologies have been hairraising at times, including offering the hire of an electric light girl: a human luminaire to light the hallways of the rich. Lighting rivalries produced early examples of fake news, trolling and influencers. Light became a propaganda tool, a weapon of war and a means of social control.

As it gathered momentum, the Great Illumination was viewed with just as much suspicion, fatefulness and fascination as today’s digital revolution. Instantaneous in historical terms but not fast enough for some at the time, its arrival, like that of smart tech, was accompanied by concerns over health, privacy and safety. It created a technological divide between town and country; radically altered work patterns; spread ideas, shaped trade and boosted consumption, all at a massive cost to the environment.

The BBC Earth Experience at London’s Earls Court. Image Credit: BBC Earth Experience: Mike Massaro

One of the lessons that emerges from the book is that the future of lighting design lies in planning, moulding and tempering our use of illumination to enhance places and spaces creatively and responsibly, says Grubb. Above all, our lit environment should be, as the urban planner Kevin Lynch put it, ‘made by art, shaped for human purposes’. In other words, lighting should serve our every interest, including pleasure. ‘When we look at a project, one of the first questions we ask,’ says Grubb, ‘is “where’s the joy?” Whatever the setting, it has to have magic.’

MICHAEL GRUBB STUDIO THE STORY SO FAR

When Michael Grubb set up Michael Grubb Studio in 2013, he did so with 15 years’ experience, awards including Lighting Designer of the Year, and the role of 2012 Olympics Learning Legacy Ambassador for Lighting under his belt.

Grubb positioned the new practice in the space between architectural lighting design and light art. An ethos revolving around community, communication and creativity was evident in early projects, including the creation of Bournemouth’s Gardens of Light festival, and Re:Lit – a long-running initiative that puts otherwise perfect lighting equipment destined for landill to use in community projects.

In typically contrarian fashion, Grubb successfully built the consultancy in Bournemouth when the conventional wisdom was that London was the place to be, but set up a second studio in the capital as remote working became mainstream.

Clients such as the Guinness Store House in Dublin and the ethical cosmetics irm Lush were key to the consultancy’s development. Many MGS schemes reach beyond lighting into narrative, particularly where it feeds into a brand or the story of a place. Story-telling and brand reinforcement were at the nub of the Guinness scheme, while at Lush Liverpool, the spa lighting works in harmony with music based on research into the pre-sleep hypnogogic state.

At Wembley Stadium Changing Facilities, the studio tapped into the skills and specialisms of the England Performance team to create lighting that aids focus, inclusivity, calming and even celebration in the event of a victory.

While Michael Grubb Studio also has large-scale projects for multibillion-pound developments, such as London’s Silver Town and Brent Cross Town, the practice

still tells more intimate but involving stories through interior lighting at locations such as Ad Gefrin, the new museum and distillery in Northumbria; the BBC Earth Experience in London’s Earls Court, and the Chimney Lift visitor experience at Battersea Power Station.

Looking back, Grubb says that from the start the practice wanted light to create a big impact in its projects. ‘It wasn’t that I don’t believe that if a scheme’s done well, you shouldn’t notice the lighting. It’s more that I don’t think there’s anything wrong with people thinking “wow, the lighting’s amazing in this place” either,’ he says.

But while straddling the architecture/ art divide helped set the practice apart, ‘the biggest difference between then and now,’ he adds, is that clients and design partners alike have a greater appreciation of the role lighting design plays in enhancing place and space. ‘Today people genuinely want to learn about light.’