California dreaming: exploring the visions of the SCI-Arc graduates

As a juror at the Southern California Institute of Architecture’s Graduate Thesis Weekend, Herbert Wright got an insight into the future of architecture as seen by its would-be practitioners

Words by Herbert Wright

There seems to be something about the name SCI-Arc that invites wordplay. Maybe it implies reaching out into the blue like a sky-arc, or a vessel for minds that is floating into the unknown like a psy-ark, and is it just coincidence that ‘sci’ is usually followed by ‘-fi’, and all its voyages of imagination?

The name actually stands for Southern California Institute of Architecture, but there’s some truth in all of those flights of fancy — when it was founded as a non-profit school in 1972 with a faculty including Thom Mayne (who would go on to win the 2005 Pritzker Prize), it was with a radical pedagogy, a ‘college without walls’ to nurture free thinking and challenge the system. Since then, alumni include another Pritzker-winner, Shigeru Ban, and its undergraduate and graduate programmes are still ranking top five in DesignIntelligence’s 2017 surveys. But does it still have that radical edge of its past? Every September, SCI-Arc stages a Graduate Thesis Weekend, and this year, I was a juror. That gave me a chance to see for myself.

Since 2001, SCI-Arc has occupied an extraordinary building just a block from the Los Angeles River in an industrial area now regenerated as the Art District. Its converted 1907 rail warehouse home was one of California’s pioneering reinforced structures, designed by Harrison Albright. It stretches almost 400m along Santa Fe Avenue, a linear box on a vast scale enclosing an industrial volume well-lit by a long stretch of clerestory windows, and it proclaims its name boldly in steel letters mounted on the roof, just like a lot of pre-war American downtown buildings did. The Graduate Thesis Weekend jurors consisted of faculty and invited distinguished academics, architects, and wild cards. I was one of the wild cards.

A view from above SCI-Arc's Graduate Thesis Weekend. Photo Herbert Wright

A view from above SCI-Arc's Graduate Thesis Weekend. Photo Herbert Wright

Still, the welcome from SCI-Arc faculty was warm when we gathered for coffee just before the first jury sessions. It’s strange that architects and mourners are the two types of people that gather wearing all black, and there was no shortage of that amongst my fellow jurors. But this was far from a funeral — it was about the future, of architecture and its would-be practitioners. Their models and visualisations seemed to fill half the ground floor.

The first two presentations I saw were puzzling, centred on harvesting urban data without any clear idea about what the data would be. Later, Vincent Ho showed his design for a Music Centre at the Museum of London site by the Barbican. It visibly expressed its 3D-printed construction — it looked like a case of form following fabrication rather than function, but it was imaginative.

After the first day, jurors were driven out into the setting sun along the Santa Monica Freeway, a luminous experience which conjured up the exhilaration that British critic Reyner Banham found driving in Los Angeles in the 1970s, when he coined the name Autopia to apply to what Lewis Mumford had called the ‘anti-city’.

The next day, my first juries were led by Peter Trummer, Amsterdam-based architect, head of the Urban Design Institute at University of Innsbruck, Austria and visiting faculty at SCI-Arc. Omar Baqazi presented a seductive, lyrical project in which Facade Gestures intervene in Georgian buildings in London, which in reality of course would be listed, meaning protected by law from the slightest alteration.

Javier Cardiel showed us his intervention in a Downtown LA site. It looked good — but his building was a car park, and that carries baggage. City centres around the world are on the rebound, but it’s people, not cars, that are bringing back life — and Downtown LA is a brilliant example. In London, we build massive buildings (such as the Shard or the new Bloomberg HQ) with five or fewer parking spaces! Jan Gehl should be recommended urbanism reading at SCI-Arc. Despite the spell Banham had cast on me, I’m the only juror who spells out the new reality: ‘cars are the enemy of the city’, I tell Javier.

For me at least, the star of that morning was Po-Hsien, who in Stages had imagined a block cut with a tight, slightly disrupted 4x16 grid of alleys and courtyards, in which events from a manga-like comic-book story animated its surfaces. Clearly the model he presented had roots in a traditional urban vernacular of the hutong, and in interplay with a contemporary graphic culture, it felt reborn in a new millennium, and super-charged.

Jacob Waas presents Eh, That’ll Do. Photo Herbert Wright

Jacob Waas presents Eh, That’ll Do. Photo Herbert Wright

That afternoon we considered some memorable projects. There was a devil-may-care confidence to Jacob Waas and the title of his project, Eh, That’ll Do. He had created a vast structure of modules like building blocks in columns, all knocked askew and splaying out in lines across the water’s edge, suggesting the figure of a slumped man. Striking and original, it provoked much analytical discussion.

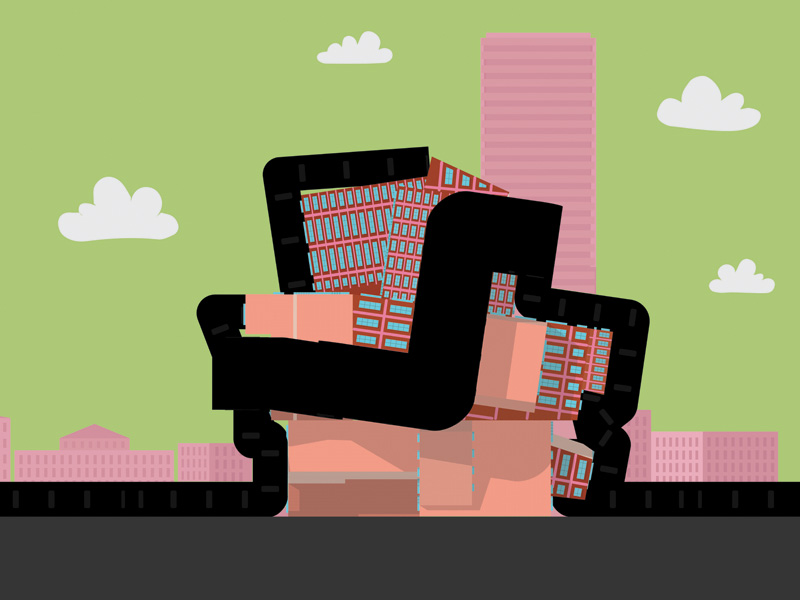

Another confident young man Conor Covey presented The Promiscuous Line [see main image], in which a thick black circulation passage wandering madly around the envelope of a partially deconstructed modernist volume. This looked fun, and engineerable, but imagine wandering through windowless tubes to reach anywhere — why not clad them in dark, Miesian glass?

Meenakshi Dravid’s Borderline Madness visualised a fascinating multilevel quarter that put me in mind of the Metabolists, but with day-glo colours. Zeinap Cinar had let blue organic patches infiltrate inside and out of a Hollywood vernacular block. The last of the day’s projects gave a very different respect to local LA vernacular and changed the mood in an extraordinary way. At the heart of Keith Marks’ work were three large photos of suburban houses, banal yet uncanny. I could feel the silence of standing there in the street before them, and a sense of mystery about what was behind those facades. That mood is something architectural representation rarely creates — it explicates the visual intent of the architect, rather than implicate the lives of the users of architecture.

The next morning saw the last round of juries. Mine was headed by Andrew Zago, LA architect and head of the faculty’s Design Studio. The following week in Chicago I would be dazzled by his own project, exhibited at the Chicago Architecture Biennial — huge overlapping grid panels with a sort of digital sheen made by physically separating metallic layers of colour.

At SCI-Arc, Jiali Carrie Li’s New Dagwood was a stacked composition of building sections differentiated by colour and function, then distorted to super-Gehry extremes. Saba Samiel’s urban plan of an entire quarter of Milan, Democratic Cohesion, was so seriously designed and executed, that it felt unnecessary to include the landmark element of a volume curving up from the horizontal with the energy of a horse rearing up on its back legs. Another meticulous effort was Palak Mandhana’s The Added Dimension, with a model of a mid-rise block that was a lot of podium and not much tower, but its PoMO facades had something of Michael Graves, and that may be timely.

Saba Samiel's Milan urban quarter in his project Democratic Cohesion. Photo: courtesy SCI-Arc

Saba Samiel's Milan urban quarter in his project Democratic Cohesion. Photo: courtesy SCI-Arc

I had several take-aways from the Graduate Thesis Weekend. The first was that there was a lot of talent being nurtured here— whether or not projects had grounding in basic issues of structure, function or context, by intent or otherwise. These students were from countries across the globe, but many seemed to have been infected with a particular California attitude — optimistic, individualist, un-hung up on convention, and often ‘stoked’ just talking about their ideas. The juries reminded me that academic language or concerns can be obtuse and arcane. If that was also the case when guiding students, some straight talk could have cut to the flaws in some projects before they became dominant. Getting real is not the antithesis of free thinking.

What I didn’t see was much political agenda. The radical spirit of architecture schools was alive worldwide in the 1970s, from the shake-up of the AA in London under Alvin Boyarsky to the professorial style (as well as the architecture) of Vilanova Artigas at FAU, São Paulo… and to SCI-Arc’s foundation. It followed from the revolutionary spirit of the 1960s, but times have changed. Today, the agenda of the US’ administration includes trashing the EPA and the Paris Agreement and walling off Mexico. My biggest message to SCI-Arc and its students is this: there is plenty of politics for a would-be architect to respond to, right now.

SCI-Arc demands imagination at the undergraduate level, and clearly, the graduates delivered it — diverse and vibrant, sometimes naive, but alive. That chimes with the founding principles of the college.