Brief Encounters: Indus by Shneel Malik is a biodesign project to depollute water

Shneel Malik tells Veronica Simpson how her biodesign project Indus can depollute water across the globe

Words by Veronica Simpson

A decade ago, I might have called myself an advocate – or even evangelist – for multidisciplinary, collaborative design, having come across this phenomenon in its early days, as fascinating projects cooked up by artists, architects and designers fused their lateral-thinking and aesthetic talents with biologists, chemical engineers or IT disruptors. Together, they threw up genuinely new materials, forms and ideas; some of which we thought might help save the planet. I recall interviewing former GP-turned-biodesigner Rachel Armstrong for this very magazine back in 2010 about her proposal to support the sinking structures of Venice with an underwater scaffold made of bioengineered coral. She even gave a TED Talk about it – TED being the obvious portal into so much of this cross-disciplinary creativity.

Nothing came of that, sadly (though Armstrong is now professor of experimental architecture at Newcastle University). Indeed, nothing came of so many of the ideas that seemed so exciting back in the day, stymied perhaps by lack of funding, lack of buy-in, difficulties in distribution, or just too many organisations having vested interests in preserving the carbon-guzzling, consumerist status quo. While the field of speculative art and design has blossomed, with several recent exhibitions dedicated to this burgeoning arena – including 2019–20’s Eco-Visionaries exhibition at the Royal Academy in London – most of the work they show is either nostalgic and utopian, downright fantastical or strictly dystopian, as if planetary annihilation was a done deal (and even Bill Gates thinks we have a fighting chance of preventing that, judging by his new book How To Avoid A Climate Disaster).

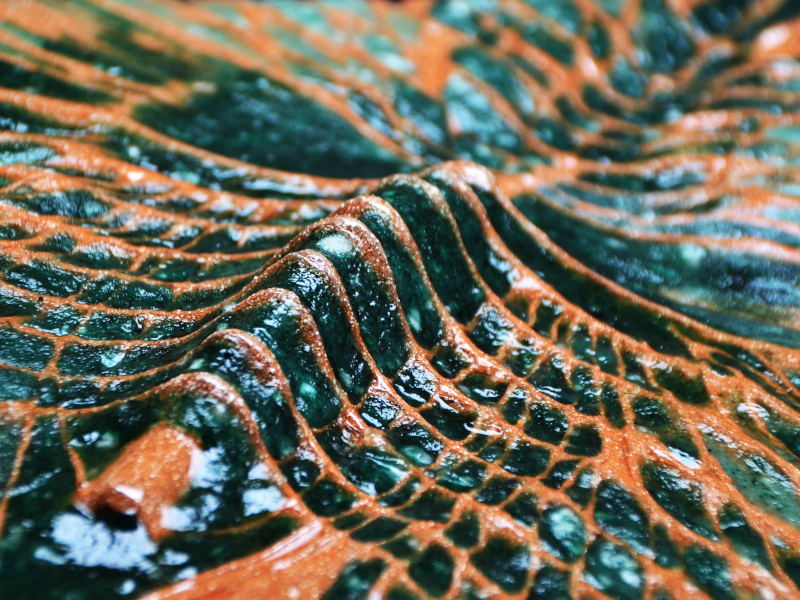

Shneel Malik's bio tiles are meant to be easily replicable for local artisans, but also bespoke for each region’s climate and pollution variance

Shneel Malik's bio tiles are meant to be easily replicable for local artisans, but also bespoke for each region’s climate and pollution variance

But then I heard about architect and biodesigner Shneel Malik, whose new invention, Indus, could represent a genuine breakthrough for small-scale manufacturers in developing countries. It was recently selected for an Arts Foundation Futures Award (£10,000 for each of the five recipients).

As the judges saw, Indus is biodesign at its best: the patterns in Malik’s elegantly crenellated ceramic tiles are inspired by the veins of a leaf – nature’s super-efficient design to speed water to where it’s needed most – and are both attractive and easily made by local artisans using local materials (although kiln firing is not the most planet-friendly technology, alternatives are being explored). Produced using a mould devised by the Indus team’s algorithms so that it is tailored to suit the scale and type of pollution for each site, the tiles are then affixed to a simple frame that is mounted on one exterior wall. The grooves in the tiles are injected with a seaweed-based hydrogel containing microalgae that can remove pollutants – even heavy metal ones such as cadmium – from waste water as it pours down the frame from outlets placed along the top of the wall. The water can then be recirculated within the factory. Although the tiles will need cleaning and refilling with algae every few months, there is nothing too expensive or technically challenging about any of it, judging by trials Malik has conducted on test sites in India – all of them textile processing factories. Malik says the tailored, small-scale approach is perfectly suited to this sector, and responds to emerging pressure from its big brand customers (like H&M), who want their suppliers to be more sustainable, coupled with local authorities’ tendency to fine factories for polluting their water sources – while offering no alternative solutions.

Malik found her niche between science and architecture

I chatted with Malik on Zoom in February to find out how she made this switch from architecture to biodesign. Having attained a BA in Architecture at Amity University, India, her desire to explore more sustainable practices inspired her to head to London in 2013 to join a new master’s programme at The Bartlett, investigating potential alliances between architecture, chemical engineering and biology. Called BiotA, it was founded by Professor Marcos Cruz, and now runs as the Bio- Integrated Design Lab in conjunction with Dr Brenda Parker, professor of biochemical engineering. The inspiration for Indus came about directly from Malik’s PhD research, with support from her course leaders.

Although interested in science, she says ‘I never knew how to bridge it with architecture. When I saw that little door slip open, I jammed my foot in it and thought: this is my spot. Terms such as bio-integrated design or biocompatible are not used within architecture. They are used within science way more. When we are talking about sustainability or green building design, these terms have been abused and haven’t been defined well enough. That’s why, as an academic and now as a potential social entrepreneur, it becomes very important to me to clearly define the remits and the ambition, plus the limitations, of what we are trying to do when it comes to biodesign.’

That social entrepreneur label is the next step. ‘UCL Innovation and Enterprise and Bio-Integrated Design Lab and The Bartlett are helping me do this,’ she says. ‘It’s a creative design-model challenge. It lets me do the design and research and development, but also lets me make it happen. For someone who comes with the vision and belief, it’s important for me to demonstrate how circular economy models and bioeconomic models can be executed.’

But there is still one problem that needs resolving: getting clients and users to understand that the material that is benefitting their water supply is a living entity and needs caring for. ‘Anything that’s living as a prototype needs to be maintained,’ Malik continues. ‘These cells need to be hydrated; they need to be gardened; they need their nutrients every now and then.’ The solution is something very analogue: that old fashioned skill of storytelling. ‘It’s important for us to tell them a story of how they really can use design in setting new standards not just for themselves but for future generations.’