Brief Encounters

Veronica Simpson discovers an innovative prototype for compact, zero-waste living in Bristol.

IT’S AMAZING how far a really gripping idea can get you. Seven years ago, Bristol based artists Ella Good and Nicki Kent were pondering what the act of envisaging living in a house on Mars could teach us about how little you might need to live well, while managing on very limited resources. The question intrigued them as much for the pleasurable leaps of imagination its answers might generate as for the obvious lessons we could learn about our stewardship of the overheating planet we’re already on. And somehow – thanks to an Arts Council grant – they found themselves turning that into a research trip to the US, where they visited the Mars Desert Research Station in Utah, as well as the Biosphere 2 in Arizona, the only closed loop biospheric system ever built.

This journey only whetted their appetite for the subject. Says Kent, ‘When we visited Biosphere 2 it became really exciting to see how you’d need to really think about everything – power, water, all the systems, as well as how do you replace things. How do you replace your toothpaste and soap? What happens when they go in the water and recirculate? It was like having a box of questions and every time we opened it we’d find 10 more questions.’

Hugh Broughton Architects helped to design the living quarters based off their experiences building harsh climate structures. Image Credit: LUKE O'DONOVAN

Well, seven years later, that never-ending box of questions turned into a fascinating and eye-catching, two-storey Martian House, sitting outside Bristol’s MShed museum. And here it sat until the end of October 2022 as a base for workshops and conversations with anyone who’s willing to take their imagination for a ride into total self-sufficiency in a hostile environment. It’s not just some casual mockup, either. This is a semi-serious prototype, thanks to all the expertise and enthusiasm the duo’s quest generated along the way.

Their self-appointed mission came to the attention of Pippa Goldfinger – yes, she is the granddaughter of the famous architect Erno Goldfinger, but also a civil engineer and architect in her own right, and head of design at Design West. She suggested they talk to Hugh Broughton of Hugh Broughton Architects (HBA), famed for the extreme environment structures they have built to survive the Antarctic’s hostile conditions. Broughton and one of his young architects Owen Guy Pearce – now set up on his own as Pearce+, and still very involved in the project – came on board in 2018. They joined in with the extensive co-design workshops the artists staged with Bristol schoolchildren and various community groups, as part of the visualization process. In this, the participants were aided and abetted by talented cartoonist Andy Council, who was able to capture the key questions and issues raised at every stage, which then informed Broughton and Pearce’s concept designs.

The upper level of the structure will also include a hydroponic farm. Image Credit: LUKE O'DONOVAN

Around the same time, some science and engineering expertise arrived from Bristol University, in the form of Professor James Norman, Dr Robert Myhill and Professor Lucy Berthoud, who between them had experience of the Mars Rover project as well as space habitat research. So the design became seriously informed by the known conditions and constraints of the Mars environment.

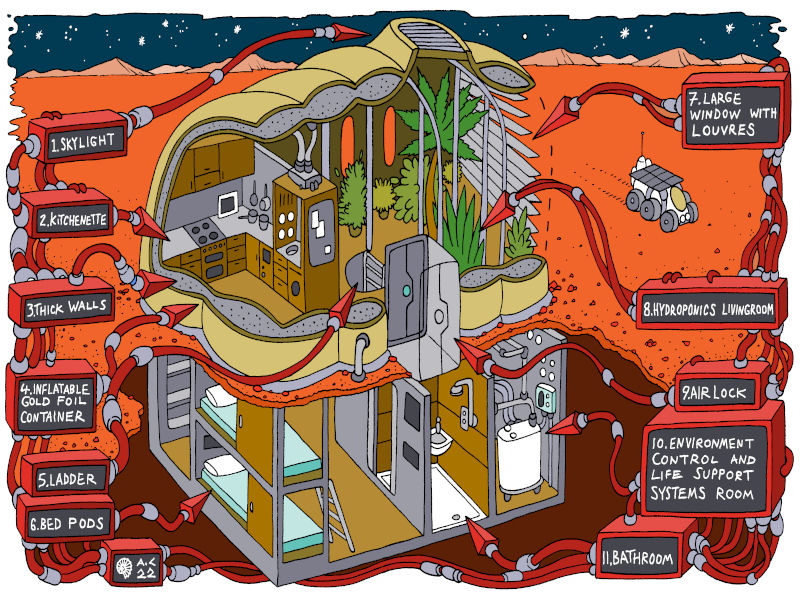

Says Broughton: ‘The scientists’ input was crucial – because of the thinner atmosphere on Mars, the much higher impact of solar and cosmic radiation, the need to protect yourself is much greater than on earth. The geology of Mars is volcanic, and they told us of these volcanic lava tubes which are quite close to the surface. So we realised we could situate the building underground in these tubes, but we knew from our polar work that buildings underground are not conducive to wellbeing – they are often smelly and gloomy. Yet above ground you have to protect yourself from solar radiation. One way to do that is to make a kind of concrete using the crust on the surface of the planet, which is called regolith. We thought you could do an inflatable structure above ground that you could fill with this concrete and use the inflatable element as formwork.’ The workshops showed that windows and vistas were considered vital for wellbeing, Broughton says. ‘So to resolve the problems of windows letting in solar radiation, we decided you can triple glaze them and have a layer of water in between, both as a way of storing water but also water acts as a filter. So you can use the upper level for growing fruit and veg, and have the living space upstairs but use the lava tubes for bedrooms and bathroom.’

The design concept for living on Mars involves an inflatable structure filled with regolith to protect from solar radiation. Image Credit: LUKE O'DONOVAN

And this is pretty much what you see on the Bristol harbourside – albeit without the lava tubes, obviously. Instead, the ground floor is created out of two containers, offering an airlock space (which is being used as a workshop), housing for all the environmental control systems including life support systems, two small sleeping pods stacked on top of each other (each pod with a restorative light box ‘view’ that can be adapted according to occupant), a loo, sink and shower unit, and a staircase to the upper storey. This upper structure is made of pressurised inflatable gold-coated foil created by specialists Inflate, and contains the hydroponic growing space, plus a ‘living room’, with roof light and windows. Pretty much all of the materials, as well as the labour, have been donated, sourced through the Southern Construction Framework. Duravit contributed the low-water, paper-free loo, drawing on their expertise from winning the NASA Lunar Loo competition. Lighting is by Whitecroft Lighting. But the project would never have got to this stage without a vital £50,000 grant from the Edward Marshall Trust. The key concepts and aims of the initiative are illustrated by cartoonist Council around the vivid red ground floor exterior and hoardings.

Over the course of its two-month stay on the Bristol harbourside, much more was expected to be designed and created, thanks to a group of volunteers the artists have recruited, who will help run workshops to explore what kinds of furniture or small essentials – or simply fun items like wallpapers or clothing – can be created which meet the aspirations of the project to be multi-functional and zero waste. Artist Dr Katy Connor, who has devised the hydroponic aspect, will be running workshops to teach about hydroponic systems, and host meditations and tea-drinking ceremonies.

‘The Martian House provides a lens for sustainable living,’ says Broughton. ‘It’s a flight of fancy, but it’s grounded in truth’. And it’s a nice counterpart to the pie in the sky, money-no- object, proposals of the tech billionaires, or the insular schemes funded by national research institutions. Triggering these conversations with the general public is far more important, as the artists declared at the press launch. Good said: ‘We are all experts in living well. The future isn’t for experts to decide for us. Usually the idea of living on Mars is born of an apocalyptic scenario. They are unhelpful and turn people off.’

Kent concluded: ‘The future should be built not just by billionaires. It’s for all of us to take part in.’

Details of this ongoing scheme are on the website: www.buildingamartianhouse.com