Beijing Design Week with Herbert Wright

Herbert Wright explores the vast, varied world of Beijing Design Week, from courtyard housing inspired by the traditional Chinese hutong to a vast design park sited on disused power plant complex

23 September - 7 October 2016

Review by: Herbert Wright

Beijing Design Week (BJDW) 2016 was so diverse, and distributed across such a vast city, it wasn’t easy getting the whole picture. Dipping into hutongs, a vast design park, and several places semi-detached from BJDW including art institutes, a property company, shopping centre and even an art hotel, as I did, revealed as much about what design and Beijing are doing to each other generally, as they did about the event’s platform. That platform is wide, strong on urban renewal but also showcasing product design and art.

BJDW is hosted by the Ministry of Culture and Beijing’s municipal government, but what were we to make of Beatrice Leanza, the locally based creative director and driving force since 2013, suddenly becoming instead director of BJDW’s overseas shows and communications? ‘Transformations are subtle and not always readable,’ she said enigmatically. Her stamp is still very much in there, notably in two core historic areas, Dashilar and Baitasi. A hutong is an alley in the dense traditional northern Chinese neighbourhoods.

A tool from the portable Shanghai Type kit designed by Li Zhiqian and Xia Shijun on show at Dashilar. Image: Beijing Design Week

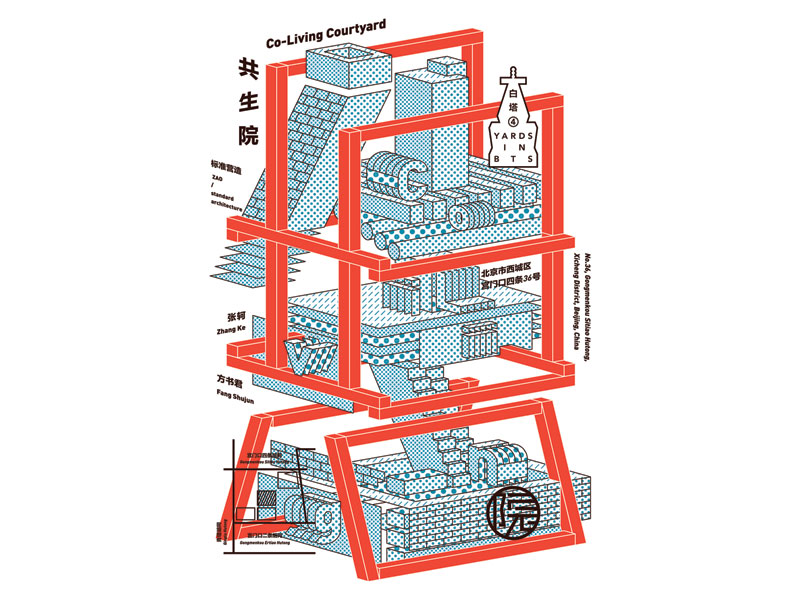

For Baitasi Remade, four Chinese architects were asked to rethink the use of hutong courtyard houses, to ‘elicit new modalities of reconstruction and accommodation of contemporary life and community needs’. Leanza also commissioned a poster for each of the built projects from prolific graphic designer Liu Zhizhi. One hutong remake was from Zhang Ke, ZAO/standard architecture head, who reconfigured a 150 sq m da-za-yuan (messy courtyard) site into one with three courtyards, shared by two properties - a minimal living unit and a whole 84 sq m of exhibition area.

Crucial to his Co-Living Courtyard is a service core with services that hutongs haven’t traditionally had: kitchen, bathroom and laundry. That element could spread across the hutongs. Zhang is a master of hutong projects, and near Tiananmen Square in Dashilar, another was one of this year’s six Aga Khan Award winners. The Children’s Library and Art Centre has transformed spaces around another da-za-yuan for the community’s children, and climbing a central structure around a tree allegedly 600 years old the sense of peace and joy is powerful.

Neon trails led to various parts of Baitasi Remade at Global School

Elsewhere, one hutong courtyard had been converted by French architect Benjamin Beller of local practice BaOi into the magical open-air BAITA cinema with wooden terraces facing a hanging screen. Practices such as reMIX Studio and People’s Architecture Office have actually relocated into repurposed Dashilar hutong properties. During BJDW, the hutongs seem to have been overrun with design. The Design Hop trail filled ubiquitously grey-brick-clad houses with cool ideas from tea and coffee houses to art-book displays and artworks.

Hip products abounded, from Yusoidea’s range of fun animal furniture called Yuso Farm, while designers Li Zhiqian and Xia Shijun showed a portable printing kit from their Shanghai Type project, made to revive interest in simple type technology. In another house, The Road Home project was resident. It had swapped three ceramic artists from Delft and three from Jingdezhen to learn the other town’s historic ceramic skills. David Derksen had patterned plates with lines traced by a pendulum, which he said referenced Spirograph (a Sixties’ geometric drawing toy) and Russian sculptor Naum Gabo.

Zhang Ke’s Co-Living Courtyard, one of the Baitasi Remade hutong projects

But it wasn’t all in the hutongs - the Dashilar Design Community (the umbrella covering all the creatives on show there) staged theme exhibitions in larger venues. The New Quanyechang, originally a neo-classical 1905 building with great internal atria reminiscent of Whiteley’s in London, hosted Open Heart Design and I AM WE on three floors, filled with cute works from a full-sized Meditating Buddha made of sugar (by galleria) to displays of gift-wrapping.

Next door, the mirror-clad Urban Pavilion had more serious urbanism exhibitions. Nearby, pop-up shops had colonised a large floor. The sparse Vanished Hospital, for example, had few clothes to offer, but offered ‘treatment for the young patients who have demands and symptoms about lifestyle and taste’. Back in Baitasi, there was also more than hutong projects. The Food Market, closed in 2015, was transformed into the Global School, a hub which for two weeks accommodated exhibitions, seminars, workshops and more.

Quanyechang (white building) and Urban Pavilion (reflective facade) hosted BJDW events. Image: Herbert Wright

Trails of different coloured neon hung through the building to provide navigation to various parts. One was Data Alley, an exhibition by LAVA Beijing that collected micro data on the neighbourhood. The Global School’s rooftop hang-out commanded great views of the nearby White Dagoba Buddhist Temple. Out on the north-eastern side of the city, the Central Academy of Fine Arts’ impressive new curvy Art Museum (designed by Arata Isozaki) was staging part of an Ethics of Technology show.

Its works involving VR headsets were not the only sources of dizziness and confusion - the show was in the BJDW calendar but actually part of the Beijing Media Art Biennale. Even further out is 751D-Park, an ex-power plant complex now given over to design. Among the paths and huge overhead pipes, Audi has plonked down a six-storey corporate block to house its Asia R&D design unit. 751D director Miranda Yan admits she is ‘still puzzled about how to contribute’ to BJDW, but this year, there was plenty of it. Dutch designer Dan Roosegaarde had erected his Smog Free tower, which looked like a polygonal office block shrunk down to just 7m tall.

It sucks in 30,000 cu m of air an hour, and removes particles by ionisation. Potentially good news for smoggy Beijing. Roosegarde’s gimmick was selling Smog Free rings with compressed soot instead of diamonds - ‘It’s emotional’, he said. But 751D’s biggest attraction was the great 79 Tank, once a gasometer, which showcased Korean capital Seoul, the 2016 design Guest City. In the dark interior, under huge seductive lampshades as big as yurts, Korean companies showed their wares. LG’s latest flatscreen television screens and Phiaton headphones indicated a big corporate presence.

There were two excellent design exhibitions at the Ullens Center for Contemporary Art (UCCA) in the famous ex-industrial 798 Art Zone, adjacent to 751D. Unconnected to BJDW but running until the end of it, A Finer Quotidian - Beyond Vision showed furniture of five international designers including Kengo Kuma and Luca Nichetto, but with dreamlike installations for each that took you into their creating minds. And Accommodating Reform: International Hotels and Architecture in China, 1978–1990, brilliantly documented key buildings with displays and models, from the time when China was opening to the world.

These exceptional shows (and a stunning retrospective of artist Zeng Fanzhi) mark the UCCA as world-class. This sampling of BJDW spot-lit two phenomena. First, that product design in China is now about looking trendy. BJDW did not have the industrial dimension of Ole Bouman and the V&A’s design project at Shekou, Shenzhen, but it did have a lot of immediacy in pop-ups. Second, the iconic hutongs, built up over centuries without architects, have lost much of their old communities (at least in Beijing) to be replaced by new middle-class residents… including architects.

BJDW’s continued efforts to bring community gain to them through design seems genuine, and a way forward. But overall, from de-za-yuans to dishes, the tension between function and lifestyle as the driver for design sees the latter blooming, like a thousand flowers.