Writing wrongs: the National Memorial for Peace and Justice

Created by the Equal Justice Initiative, the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama, solemnly remembers the black victims of lynching in the USA

Words by Adina Solomon

Progressing through the National Memorial for Peace and Justice feels like a journey. The summer day’s heat has just started to get thick, and a gravel path leads visitors to the first of many statues — a group of partially clothed slaves struggling in chains, created by Ghanaian artist Kwame Akoto-Bamfo. The man in the front of the group stands upright and looks ahead, as if facing his fate.

On the other side of the path, a precast, shuttered concrete wall bears placards with facts about the history of black people in the United States. More than 4,400 lynchings of African Americans have been documented; only 1% of lynchings committed after 1900 led to a criminal conviction. The dark grey wall, reaching 3.6m at its highest point, surrounds the entire memorial grounds.

Set on a hill in Montgomery, Alabama, not far from the Maya Lin-designed Civil Rights Memorial (1989), the 2,800 sq m National Memorial for Peace and Justice — a square, open-air pavilion in landscaped grounds, which opened in April — sits solemnly. Its location in the South near the church where Martin Luther King Jr served as pastor is fitting.

‘[Montgomery] has such a history of civil rights that we thought it important to embed this history of lynching in that deeply historical city,’ explains Sia Sanneh, senior attorney at the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI), the Alabama-based, non-profit, legal organisation that created the memorial. ‘What’s more, the history of the city is deeply shaped by the domestic slave trade. Montgomery was once one of the most active domestic slave-trading spaces in America.’

The first thing visitors see on entering the memorial is a sculpture by Ghanaian artist Kwame Akoto-Bamfo, depicting a group of slaves struggling in chains Image Credit: Adina Solomon

The first thing visitors see on entering the memorial is a sculpture by Ghanaian artist Kwame Akoto-Bamfo, depicting a group of slaves struggling in chains Image Credit: Adina Solomon

The memorial is dedicated to remembering black victims of lynching in the USA. But the first step in remembering is education. ‘Most people did not have and still do not have an accurate understanding of what lynching is,’ says Sanneh. ‘People, if they know anything about it, think it was a sort of frontier justice or vigilante violence. And we try at the memorial to get people to understand that this was really systematic — it was designed to systematically oppress people of colour economically, socially, politically.’ The memorial also explains how lynching created mass migration: because of the constant threat, six million black people left the South between 1910 and 1970.

The National Memorial serves as a companion piece to another project founded by EJI, the nearby Legacy Museum, which opened on the same day as the memorial and is dedicated to the history of slavery and racism in the USA. The museum is housed in an existing two-storey, brick building on the site of a former warehouse where enslaved black people were imprisoned.

The memorial is linked to the nearby Legacy Museum, housed in a building on the site of a former warehouse where enslaved black people were imprisoned. Image Credit: Equal Justice Initiative

The memorial is linked to the nearby Legacy Museum, housed in a building on the site of a former warehouse where enslaved black people were imprisoned. Image Credit: Equal Justice Initiative

The two projects cost a total of $15m (£11.4m) to build, raised from private donations. The land on which they are built belonged to the City of Montgomery, which ‘wholeheartedly’ approved the sale to EJI in 2015, according to Montgomery’s senior development manager Lois Cortell. ‘We are truly proud of the Memorial and the part we played in helping ensure it was built,’ she adds over email.

To create the memorial, EJI — led by executive director Bryan Stevenson — spent almost seven years researching lynchings in the USA. ‘The memorial is the physical manifestation of historical research by EJI staff, to try to document the way that racial terrorism has shaped the landscape of the American South and beyond,’ explains Sanneh. ‘There are dozens of current and former EJI staff, including lawyers, justice fellows, social workers, interns, law students and more, who worked tirelessly to gather the data that forms the basis of the site.’

EJI partnered with Boston-based MASS Design Group and several artists — Akoto-Bamfo, Hank Willis Thomas and Dana King — to realise the project. Interestingly, MASS declined to speak publically about its involvement with the project. ‘We’re honoured to have collaborated with EJI,’ the firm told Blueprint in a statement. ‘It is important to think about how the story of the project is told, however, and keep the focus on a narrative of racial injustice. This is best communicated by EJI and as such we fully support them serving as the voice of the project.’

Eight hundred 1.8m-long rectangular corten steel monuments drop down from the roof of the memorial square, one for every American county where a lynching took place. Image Credit: Adina Solomon

Eight hundred 1.8m-long rectangular corten steel monuments drop down from the roof of the memorial square, one for every American county where a lynching took place. Image Credit: Adina Solomon

Sanneh elaborated on this, explaining why EJI, also, was hesitant to discuss the memorial’s design: ‘For decades, people have looked for ways to avoid confronting the history of lynching and racial terrorism, and to engage instead with topics that are more comfortable; we are all still working hard to avoid that even as people are moved to respond to the physical elements of the site, including the design and artistry involved in creating it.’ To the suggestion that one can speak about how design communicates educational and historic messages without undermining the meaning of a project, EJI declined to comment.

The history of slavery and lynching is indeed woven into the memorial. The design is stripped-back, leaving room for people to inject their own thoughts and come to their own understanding as they progress through the site. ‘It’s that simple way of design that makes you think,’ Sophia Shikwambi, a visitor from San Antonio, Texas, said on my visit.

The memorial’s simplicity also serves to render it a place of dignity for victims, Sanneh explains. Lynchings were usually public spectacles where spectators brought their children, so EJI avoided this sensationalising of death by not using graphic imagery.

Each monument bears the victims’ names from the county it represents. Image Credit: Equal Justice Initiative

Each monument bears the victims’ names from the county it represents. Image Credit: Equal Justice Initiative

The memorial starts with that sculpture of slaves by Akoto-Bamfo, reminding the visitor of how slavery and lynching are intertwined (when the USA abolished slavery in 1865, it didn’t stamp out the way of thinking that provoked lynchings for many years to come). After the sculpture, the gravel path snakes up to the memorial square, a minimal, open-air, peristyle-like structure on a grassy hill. From the top, visitors can spot the state capitol building and the Alabama River.

A total of 800 1.8m-long rectangular corten steel monuments hang from the black roof of the memorial square structure, one for every American county where a lynching took place. Each one bears the victims’ names. On entering, visitors confront the suspended corten monuments at eye level. The Kebony wood floor then descends lower into the structure’s concrete base, creating the effect of the steel slabs slowly rising over your head. Suddenly, it becomes apparent just how many monuments this memorial has. Sophia, the visitor from San Antonio, said it felt nerve-wracking to step underneath these hundreds of hanging monuments. They felt too much like suspended people.

As the floor descends, the steel slabs appear to slowly rise over the visitor's head. Image Credit: Equal Justice Initiative

As the floor descends, the steel slabs appear to slowly rise over the visitor's head. Image Credit: Equal Justice Initiative

The walkway continues to lead you around the square, beneath the sea of suspended monuments, inviting you to reflect on the thousands of victims’ names. One side of the memorial square has epitaphs on the concrete wall with the names of victims and why they were lynched. The reasons include eloping with a white woman and ‘standing around’ in a white neighbourhood. ‘They’re telling you these one-lines about people that are very provocative but we thought really helpful for people to learn, to understand why people were lynched, just how minor these social transgressions were that prompted people to lynch,’ says Sanneh. At this point, if visitors need a moment, there is a place to sit and reflect.

The final side of the square on the visitor’s journey has a wall with water streaming down, a peaceful sound, with a movement that recalls tears. A clear box perched in the middle of the hallway contains soil from more than two dozen lynching sites around the country. The green grass of the open space in the memorial’s central courtyard represents the courthouse lawns where lynchings often occurred.

The memorial square — a minimal, peristyle-like structure — sits on a grassy hill overlooking the city. Image Credit: Equal Justice Initiative

The memorial square — a minimal, peristyle-like structure — sits on a grassy hill overlooking the city. Image Credit: Equal Justice Initiative

Exit the memorial square, the rushing sound of water still ringing, and duplicates of the hanging monuments lie flat on the ground, one after the other. The 800 monuments are arranged in the shape of one of the massive ships that brought slaves from Africa to the USA. Each county’s duplicate monument is available for that county to take and erect locally. None have been formally claimed yet, but quite a few counties have reached out, Sanneh explains. If counties start claiming their monuments, the ship will disappear over time.

The sheer number of monuments, their crusted corten hulks laying like caskets, feels overwhelming. I seek out the Atlanta county where I grew up, Fulton, and see its monument lists 35 lynching victims, many of them unknown, from 1889 to 1936. A glimmer of progress awaits visitors after they leave the expanse of monuments. There’s a sculpture by Dana King of women during the Montgomery Bus Boycott, a civil rights protest in 1955 and 1956 against segregated seating on city buses. ‘Seeing that sculpture after leaving the memorial, it just hit me for the first time that these women — who launched one of the most successful people’s movements in history and effort of community organising — they grew up in a period when people of colour were dragged through the streets and set on fire and burned for things like not stepping off the sidewalk when a white person was passing,’ says Sanneh.

The nearby Legacy Museum, another EJI project, is dedicated to the history of slavery and racism in the USA. Image credit: Equal Justice Initiative

The nearby Legacy Museum, another EJI project, is dedicated to the history of slavery and racism in the USA. Image credit: Equal Justice Initiative

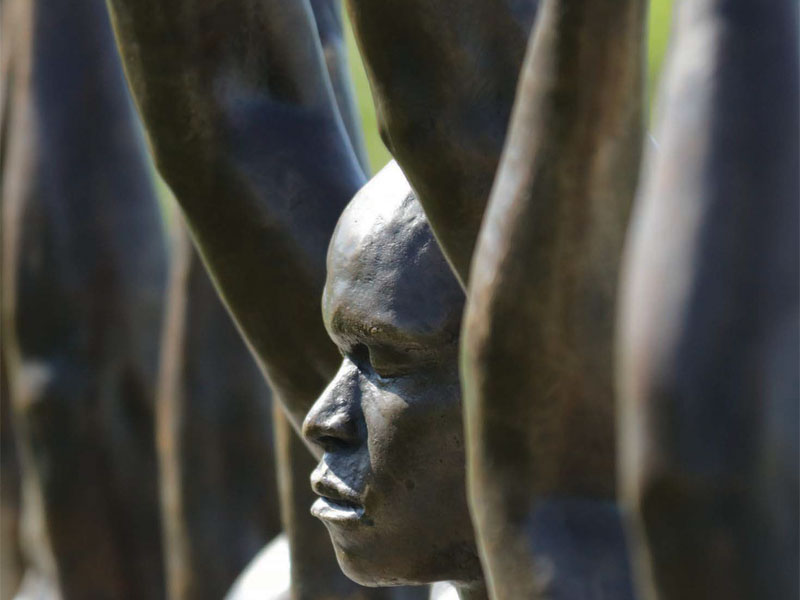

Continuing down the hill, there is a more abstract sculpture by Hank Willis Thomas, inspired by the image of people in police custody lined up [see main picture]. The figures raise their hands in the air. The Montgomery memorial draws influence from others around the world — the Kigali Genocide Memorial Centre in Rwanda, the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe in Berlin and the Apartheid Museum in Johannesburg. Shamani Shikwambi, Sophia’s uncle, lives in Macon, Georgia, but he grew up in Namibia under apartheid. He says the Apartheid Museum and the National Memorial for Peace and Justice share similarities. ‘It’s a sacred space,’ he says.

The memorial design also inspires understanding and conversation. Shamani teaches, saying he plans to talk with his students about people’s responsibility today for the issues raised by the memorial. ‘These things are going on still,’ he says. ‘Lynching still continues in 2018, but in a different format — police brutality that we see every day, the incarceration of people of colour, this prison pipeline that has been created particularly for young black men in this country. What does that mean and what is our role as neighbours, as citizens? When we have politics that are so polarising day by day, how does that play out of ourselves?’