Museums and mindfulness

How do museums engage people with the three-dimensional, physical relics of human civilisation in the age of ubiquitous two-dimensional digital distraction? Veronica Simpson searches for curatorial solutions.

Words by Veronica Simpson

A thing of simple, utilitarian beauty has appeared on a slag heap in northern France. An outpost of the Louvre Museum in Paris, that the Louvre Lens is there at all is remarkable; a symbol of the most optimistic belief in arts-led regeneration.

The conical black towers of coalmining refuse appear on the horizon long before the train from Lille shudders into Lens station. SANAA, the Japanese architecture practice, wanted the building to celebrate the region's industrial heritage, not ignore it.

And its intervention perches lightly on the once blasted earth, looking much like a translucent, elongated aircraft hangar, with interiors of poured concrete and silvery light diffused through the exterior of glass and polished aluminium panels.

A benevolent calm pervades the building. Its multiple reflective and curving surfaces transform the other occupants into blurred beings who shimmer vaguely as if perceived through fog, ether or sleep. It's an other-worldly space: like entering the antechambers of heaven (or hell?); the contemplative quiet of a futuristic funeral parlour merging with the hum of a modern-day Apple store.

Of course the Louvre Lens would have to be something very different to drag people to this neglected corner of northern France, away from the delights of historic Lille or the First World War graveyards and memorials over the Belgian border. But the real drama comes in the main gallery, the 120m-long Galerie du Temps, where 4,000 years of art and antiquities, from ancient Syrian sculptures to Delacroix's Liberty Leading the People, is displayed with delicious irreverence for time-honoured curating traditions. Paintings, statues, carvings, rugs, mosaics and gilded reliquaries appear to float freely in one vast, narrow space, though in fact they are placed strictly chronologically, their date of origin matched to a timeline etched into the far wall.

This curatorial approach is radical, but it works. Freed from the need to pace obediently around one topic/continent-specific room or section after another, plodding from text to object, these glorious items appear more vivid, the connection with them more direct, as you get up close and personal. The freedom to cherry-pick your route -- with the entire landscape of the gallery, from start to finish, visible in one generous sweep of the eye -- is empowering, emphasising both choice and responsibility.

We visitors feel like engaging more, not less. And it makes us more aware of the others in the room, the journey they are on, the conversations they are having, both with each other and with the artefacts. It becomes a more collective experience. And all without an iPad or touchscreen in sight.

For the Galerie du Temps, the Louvre Lens has opted to be screen free. There are, of course, hand-held devices available. There is very little in the way of text in the main Galerie: captions and explanatory panels are brief, and placed at shin height, so it's the artefacts that fill the visitor's field of vision. This smorgasbord of civilisation, offered in such an informal way, is exhilarating, especially to the young: here is a naturally ventilated space filled with filtered daylight and so very different from the oppressive grandeur of a great, 'civic' building. It allows them to roam and dwell as they wish -- free-range culture lovers rather than battery farmed.

Behind its programming is a huge amount of thought about the key dilemma for the 21st-century museum: at a time when everything people might want to know is available to them at the click of a mouse, how do museums make their collections and knowledge meaningful and vital? How do they use technology and design to enhance the physical and intellectual experience rather than distract? How do they expand their audience against so much online, on-demand competition?

Ten years ago most museums thought they were pretty progressive if they offered a couple of screens for archive investigations, a handheld audio guide, and an interactive or two for the young. Now, the connections between visitor and object are being mediated in a far more complex and fascinating, often multilayered, dialogue, involving a wide range of technology -- or, as with the main Louvre Lens gallery, barely any technology at all.

James Peto, senior curator at London's Wellcome Collection, says: 'I think people have latched on to that having lots of things to fiddle and play with doesn't add anything to the visitor's understanding. Usually the button pushing is about demonstrating "This is how it works". We try not to demonstrate but inform by provoking people's interest, to get them to ask questions.' To this end, the Wellcome Collection -- which began its much-admired series of exhibitions dedicated to exploring medicine and the human condition only in the past decade -- tends to work with artists who use film, installation or sound (see case study). For example, in the current exhibition on consciousness, States of Mind, Belgian artist Ann Veronica Janssens creates a cloud-filled room to demonstrate how easily the senses can be cloaked and confused.

Meanwhile, one of the UK's oldest institutions, the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, is exploring all the interesting margins of technological engagement. An online blog has been offering downloadable sound-files of spoken word, ambient recordings and music, linked to specific exhibits in the Fitzwilliam and several other museums run by Cambridge University (see The Seven Heads of Gog Magog case study).

David Scruton, the Fitzwilliam's documentation manager, in charge of digital programming, agrees that audio content can provide a powerfully immersive experience to heighten the visitor's connection with the artefacts themselves. 'We are trying to engage people with objects in a different way than you would normally expect. The intention [of the blog and soundfiles] was that people would download the files and bring them into the gallery. But it also works independently of that.'

Scruton is currently steering the Fitzwilliam through to the next phase of digital engagement, having recently removed the multimedia guides introduced 10 years ago. Says Scruton: 'The idea of the guides was to introduce information that would be difficult to offer otherwise with a limited amount of room in the gallery -- so, it was primarily the interpretation of the object.'

It performed that task moderately well, though there were drawbacks: 'Our first experience of the first mobile guide was that it was difficult to use; people were spending time just learning how to use it rather than accessing the content.

You have to see digital technology as part of a range of techniques for interpretation. Its real value is not just interpretation, but what you can do beyond just providing information.' Lucy Theobald, head of press at the Fitzwilliam, says: 'There is no substitute for looking at a physical object. Our digital platforms team has made a strategic decision not to have too much of our collection online. When we have an exhibition website, we will choose a select number of objects to tell the story.

Large high-resolution images don't currently exist on our online platform. Instead, we are trying to think about the experience that people are having when they come through the door, creating intelligent connections between objects in a gallery, rather than telling one straight story.' The exhibition Treasured Possessions earlier this year was a case in point. A meditation on early forms of consumer culture, it was about, says Theobalds 'creating a real and human connection between the objects and their owners, looking at who they belonged to, how they were used...You were being asked to have a personal connection to the way things were acquired in the past. There were digital interfaces but only to tell the stories that cannot be otherwise told in the gallery - for example, objects that cannot be opened or that have secret compartments, like a travelling knife-and-spoon set, will be shown being undone in a video so you can see the spoons and how they were twisted together'.

Experimental projects such as The Seven Heads of Gog Magog are all about targeting a different, younger audience, active on social media, in the hope of tearing them away from Facebook and into a museum on a Saturday afternoon. But social media is also being used by museums to encourage hands-on engagement of an entirely different magnitude -- harnessing existing and latent communities in the design and creation of exhibitions from the outset.

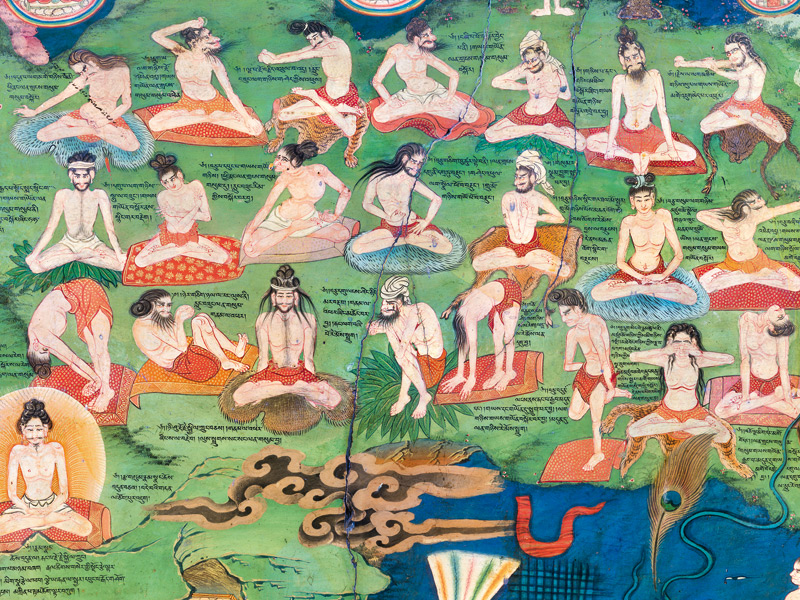

Feature image: photo of Tibetan Mural, © Thomas Laird, 2012

Case Study

True Rotterdamers: Can we make it? Museum Rotterdam

Currently without a permanent base, Museum Rotterdam for the past two years has adopted a socially interactive model of exhibition creation -- inviting people to participate in devising exhibitions and being part of them.

In the same warehouse space used for Echte Rotterdammers, the latest exhibition on crafting and making was co-created by the museum with a group of around 150 small-scale makers. Via workshops it devised an exhibition that explored the 'connecting force' of making. Says curator Nicole van Dijk: 'Our interest was not reserved for unique, creative or cutting-edge activities, but also for how working with the hands can help connect city dwellers.'

Putting makers into four categories -- textile, food, wood and metal, assembly and repair -- displays on these were placed at the perimeter of the exhibition, while the centre was formed by four 5m-long maker tables, supplied with all the materials and tools needed for visitors. Says van Dijk: 'The idea was that, through offering such a variety of making experiences, people would come back and gradually explore the exhibits around the edges of the making space.' A/V screens are part of the exhibition, 'but mainly they are there to provide information or show a film about a technique. The only really interactive thing is doing the work yourself with your hands and the materials on the table. And that is the whole point.'

Client Museum Rotterdam

Curator Nicole van Dijk

Design Museum Rotterdam, Ron Breugelmans

Area 1,250 sq m

Cost €200,000 (building, design and workshops during exhibition)

Dates October 2014 - March 2015