Man Machine: the visionary work of Dr Fritz Kahn

After looking at the graphic visualisations of the human body and its organs as devised by German scientist, gynaecologist and author Dr Fritz Kahn as a way to explain complex functions, it may not be possible to think of them in any other way again

Words: Steven Heller

How often have you imagined that little humanoids control our every move in the multi-leveled factory that comprises the human body?For those, like me, who are confused by the language of science, simplification through metaphor and analogy are common in order to comprehend the complex mechanics of everyday human existence. This is how the rediscovered visionary, Dr Fritz Kahn (1888-1968), a German scientist, gynaecologist and author, tapped directly into our collective conscious and subconscious.

'In the plate "Man as Industrial Palace", an attempt was made to depict the most important processes of life, which can never be observed directly, in the form of familiar technical processes so as to provide an overall picture of the human body's inner life' (1926) All images taken from the Fritz Kahn Monograph Published By Taschen

'When we are awake' and 'When we are asleep' (both 1939) All images taken from the Fritz Kahn Monograph Published By Taschen

While the notion he adopted was admittedly absurd, even naïve, his work then developed it into an effective learning tool - and an iconic, copyrighted graphic system that brought this metaphor to virtual life. If Kahn is remembered for any single accomplishment during his formidable and storied career, it will be as author of the subversively comical yet decidedly resolute diagrammatic wall poster titled Der mensch als industriepalast (Man as Industrial Palace, 1926), where he graphically transformed a human body into the mechanised factory we often imagine it should be.

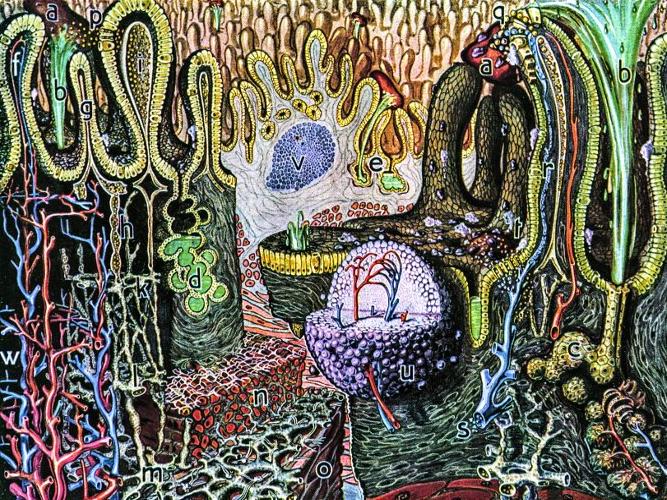

'Entering a gland cave. Ideal landscape picture of the microscopic structure of a man's body' (1924) All images taken from the Fritz Kahn Monograph Published By Taschen

Kahn found an eye for visualising data decades before data visualisation became a recognised method for processing and interpreting information. His 'Industriepalast' poster, a surreal rendering (as precise as any Dalí and as ironic as any Duchamp) of a schematic, cut-away human head and armless torso, exposed mazes of intersecting apparatus housed in compartments and bound to one another by the efforts of specialised homunculi (those little humanoids), each a patently skilled labourer wearing a lab coat, work clothes or business suit, depending on their respective hierarchical or class status within the body. These 'individuals' ensure the smooth progression of all the bodily functions as though they were working a normal shift with any industrial manufacturer. In fact, these meticulous machine-age wonders are the body's organs, muscles and nerves, better understood in their anthropomorphic forms.

'Travel experiences of wandering cell: on top of the nasal conchae inside the nose' (1924) All images taken from the Fritz Kahn Monograph Published By Taschen

'Travel experiences of wandering cell: in the dust storm of the windpipe' (1924) All images taken from the Fritz Kahn Monograph Published By Taschen

Every part of the body had its own avatar (before such a thing was coined) - the eye is a bellows camera, the lung is made of copper tubes, the stomach and intestines are fast-moving conveyor belts doused with pressurised hydraulics. The poster further reveals the left and right parts of the top of the brain where studious homunculi are seen busily reading, drawing and conversing. Lower down, once food is consumed, it slides directly towards the bowels, where workers physically break it down into sugars and starches and other components to be conveyed along the disassembly line into nearby digesting-rooms. Although I wouldn't want any physician of mine to have this on his examining-room wall in place of a Gray's Anatomy chart, Kahn was such a master of his métier and pioneer of information graphics that a viewer could not help but be entertained as well as informed by what would otherwise be cold, clinical information. This and other diagrams were so profoundly and widely appealing that Kahn's influence spread throughout the world during his lifetime and is clearly manifest in various media today, long after he died, even if his name has been forgotten.

The cycle of matter and energy. All images taken from the Fritz Kahn Monograph Published By Taschen

'The number of bacteria in the air in a metropolis. People recognise the exceptional importance of watering the streets to keep down the dust and of disinfecting the air, as well as the health hazards accompanying all large crowds' (1926) All images taken from the Fritz Kahn Monograph Published By Taschen

A once-ubiquitous US TV commercial in the Fifties and Sixties advertising Bufferin showed the painful image of a sledge-hammer torturously pounding away inside an X-rayed head to approximate the feeling of a headache. It was a Kahn rip-off. Yet in Kahn's universe, the intricacies and subtleties of human bodily functions were more fascinating than the facile attempts of Bufferin's ad agency to reduce a complex medical problem to the mere pounding of a cudgel. His primary mission was to remove the mystery from biology and pathology by presenting it through words and pictures that most people could comprehend - and even enjoy. Paradoxically, his own words were a bit more obtuse: 'The cell state is a republic under the hereditary hegemony of the mind's aristocracy,' Kahn wrote using the arcane terminology of socio-political language, 'its economic system is a strict communism.'

'What goes on in our heads when we see a car and say "car"' (1939) All images taken from the Fritz Kahn Monograph Published By Taschen

'The lifting capacity of a man's skin is so great that a strip of skin 3cm wide is capable of bearing the weight of the whole body' (1929) All images taken from the Fritz Kahn Monograph Published By Taschen

Kahn and the visual linguist Otto Neurath, founder of isotype (International System of Typographic Picture Education), were two halves of the same pie chart. Although it is probable the two never met, each passionately sought to devise a distinct graphic design language to replace jargon and lay waste to an ever-growing Tower of Babel. Neurath, a philosopher, scientist, sociologist and political economist, could not actually make the signs and symbols he was known for. Kahn was not an artist either yet he compensated nicely through his powers of logic. He also hired professionals to follow his dictates and expand his tastes. His graphic-design preferences were eclectic and included such methods as photo-collage, painting and drawing and styles such as comic, surrealist, dada and more. The art of analogy was Kahn's forte (sometimes to the extreme): he might compare an ear with a car or a feather with railroad tracks, all meant to explain ever more impenetrable phenomena by means that triggered the viewer's imagination. Kahn employed whatever visual tricks he could cobble together for the end result: popular comprehension.

Fritz Kahn demonstrates the functions of the cerebral cortex (1929) All images taken from the Fritz Kahn Monograph Published By Taschen

The 'Industriepalast' poster may be Kahn's most emblematic work - it has certainly up until now been the most visible - but it is not the only noteworthy piece in an extensive oeuvre. Some of his work was more cartoon than diagram and more narrative than didactic. The incredible and fantastical tableau of the lone female homunculus riding on the cell while surfing the gland cave is reminiscent of Max Ernst's later works, while there are also cellular landscapes that rival any science-fiction illustration where biological patterning is a leitmotif for visual storytelling.

'In 70 years, a man eats 1,400 times his own weight' (1926) All images taken from the Fritz Kahn Monograph Published By Taschen

Kahn also embraced modernism and those responsible for it and his own followers included the Bauhauslers Herbert Bayer and Walter Gropius. He avidly employed new technologies as visualisation tools for explaining the invisible physical world, such as the senses of smell and sight. One of his most illuminating diagrams, among the many, was 'What goes on in our heads when we see a car and say "car"', a complex orchestration of functions starting with the eye, imprinting a message on a film-strip that leads to a projection booth, inhabited by a homunculus projecting a photo of the car on to a screen that relays this image to a second screen that displays the word 'car'. The message subsequently is broadcast to a pipe-organ which then toots out the word. If only it really worked this way... Nonetheless, Kahn saw the process operating in this way and made his viewers see it the same.

'Iris diagnosis, or the art of identifying illnesses from the appearance of the eye, using an "iris key". Changes in the iris are thought to be associated with illnesses in the various organs, as shown in their corresponding positions in the picture above' (1931) All images taken from the Fritz Kahn Monograph Published By Taschen

The legacy of Kahn's work has resonance now and this will continue into the future. The assembly of his little-known and lesser-known images in this book is nothing less than a treasure of conceptual thinking. After seeing the connections Kahn had made, it may be impossible to look at the human body or any similar composite structure in quite the same way again.