If you build it: the rise and rise of self-build

Self-build, custom-build, collective custom-build - we’ve always been a nation of DIY lovers, and now the British housing crisis is spurring on several do-it-yourself alternatives to the hegemony of the volume housebuilder. Blueprint has assembled a panel of architects, developers, researchers and strategists to share their perspectives on this emergent field

Words: Shumi Bose

It will come as no surprise to most readers that the UK is in a severe housing crisis - so scream the daily headlines. TheGovernment's financial policies, intended to boost the market, will succeed in pushing up house prices further and, in any case, do nothing for those excluded from the housing ladder. At the same time, development policies have undergone chaotic changes in the past few years, from neighbourhood planning frameworks to reckless conversions of purpose. Viewed together with struggling market conditions, volume house builders have not been incentivised to get on with providing the numbers that we need.

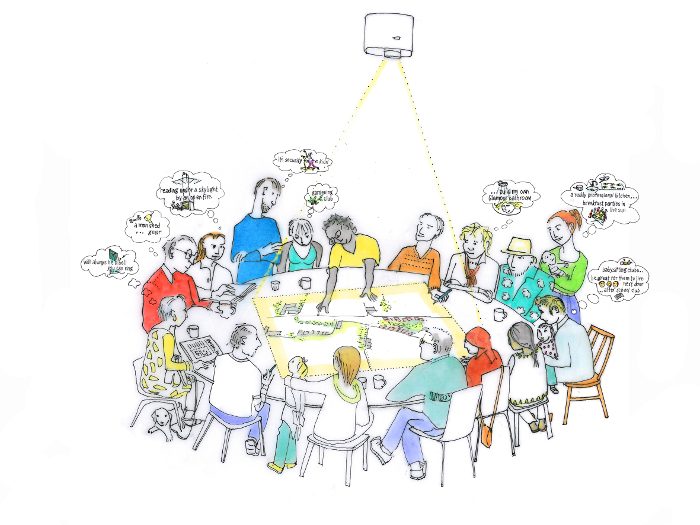

Cartoons illustrating the multiple desires of a collective building group, drawn by Cany Ash Courtesy Ash Sakula

While this knotted situation tightens, there is an emerging yet distinct current of do-it-yourself energy complicit between the construction professions and imaginative clients: a way out of the bind is sought through innovative models of self-build and its nascent offspring, collective custombuild (see Infographic, page 25). These terms can conjure flawed preconceptions: hippyish commune dwelling for the latter or private dream housing for the former. There are myriad definitions and interpretations, but what self-build and collective custom-build initiatives do have in common are the offer of side-stepping the large volume housebuilder, providing a greater degree of choice to the consumer, and a freedom from the banality of the minimum-standard designs which tend to be rolled out en masse. Other benefits - particularly in the case of collective build - include a greater sense of community, shared responsibility and neighbourhood interaction.

Across the Channel in Europe, particularly in Austria and Germany, self-build models such as Berlin's Baugruppen (see Listen, page 17) make up a major proportion of new-build housing provision. Further afield, the 'fideicomiso' collective building contracts common in Buenos Aires were featured in the British Pavilion at the 2012 Venice Architecture Biennale, as an idea we might learn from. However self-build is not new to Britain: witness Walter Segal's much studied efforts to develop self-build models in the 1970s - conceived during another period of economic duress, but still valuable today. Despite the complexity of legal and planning issues in this country, increasing numbers of architects, researchers and even developers are looking into new ways of working, and they are backed by the Government's urgency to provide more housing; there is a definite building of momentum. For this special feature, Blueprint has invited a cast of players in the self, collective and custom-build field to share in their own words their thoughts and experiences.

Solidspace

Gus and Roger Zogolovitch

Solidspace is on a mission to build 'homes to love', geared towards modern living without compromising on quality, efficiency or style. The designs are characterised by a split section form, allowing for a flexibility of function and maximal use of plots. Headed by father and son team of architect-turned-developer Roger and Gus Zogolovitch, Solidspace combines Roger's design and development experience - built over a career spanning four decades - with Gus' business acumen and enthusiasm for self-build.

Gus Zogolovitch: Eric Pickles has recently (Oct 2013) announced more governmental support for the idea of self-build. There seems to be a political and professional force behind self-build; with our company Solidspace, it is one of the key areas that we want to look into.

To rewind a little, I did my own self-build house several years ago - anyone who has done their own project is usually converted to the process. I wear another related hat, as a committee member of National Self Builders Association (NaSBA). According to NaSBA research, approximately one million Britons are actively looking how to do self-build now; the number of people who actually do it, is more like 10,000, a 99% drop off. We produce the least self-build as a percentage of new builds, as compared with places like Germany and Austria.

Gus Zogolovitch's own Zog House uses the split section to maximise use of space Photo credit: James Brittain, Courtesy Solidspace

Incentivising the home owner

Gus: In basic terms, what self-build does is take the incentives away from the volume housebuilder and puts them back into the homeowner. A volume housebuilder is profit-driven; they pay for a piece of land and set house prices based on comparables, rather than the cost of producing units. So you can imagine what happens: units are often built as cheaply as possible or to maximise their number. When land is a scarce resource, and profit is the motivation, ultimately the thing that suffers is the house itself.

A self builder doesn't necessarily need a profit, or to build in terms of local competitive value. Mostly they're saying, 'I'm building something for myself, I want it to last, I'm going to spend what it takes.' There's a statistic that says the average cost of a new build speculative home is £170,000 and the average spend on a self-build is about £250,000. So people are basically spending more on their homes. And that spending more normally translates to better quality design, better quality of build and so on.

Developers versus self-builders

Gus: It's very small at the moment but the 'big boys' of development are looking at it - whether they will be able to pull it off too is difficult to say, as there might be a cultural mismatch. The problem is ultimately about scaling up. Our view is that in self-build people are so incentivised by all this good stuff - good design, longevity, building community - actually that's what drives us, our mission is to build really high-quality homes. The Government is putting a lot behind self-build - not least because self-builders keep building when there's a credit crunch - but also because it recognises the same thing: it's saying 'Let's try and support this sector'.

But you can't very easily support single self-builders; as a self-builder you need lots of intervention and help. What that has created is an interesting fledgling industry called custombuild. Custom-build is, in a sense, a hybrid between self-build and speculative development - it actually takes the speculation out of it and, to some extent, you get the best of both worlds. There are lots of definitions of custom-build, but the one that we use is to say that you get a developer to manage the process for you - so effectively you get a fixity of price and delivery, and a fixity of quality in some certain regards. Yet you are still in control of what you want to put into a house and you can have a lot more control about the house you want to live in.

Customer as client

Gus: Having control from the outset means that, as a customer, you effectively become the client. Recent - slightly scary - research suggests that approximately 75 per cent of us would not want to live in a new-build home, if given the option. In a way, that's where Solidspace comes in. We think we have a product that appeals to that majority - it's not the disagreable standard, because we take the design, the feel and the client's needs very seriously. That's why for us custom-build fits very well with where we want to go as a company. It's attractive to our target market - people who want to have some control, as they're used to having some control in every other aspect of their lives. If you're buying a car, you can have a whole load of customisation; your phone, I'm sure, is programmed with all sorts of apps to the ones that I have. It's almost a democratic ideal, and it's back to this collaborative sharing society: Twitter, for example is where we get our news from and people are watching things shared on YouTube - we're used to collaborating and actually creating content. We haven't seen that in housebuilding so much, and custom-build is about providing that opportunity.

Essex Mews: Splitting living areas across three levels gives a sense of movement and space Photo credit: Dominic French, courtesy Solidspace

Creative development

Roger: The interesting thing as far as I'm concerned is from the creative and design side of things - because I am an architect. But for the past 30 years I have engaged positively as a progression in my architecture career with my notion of commerce, as a developer. Those notions are to do with how the architecture profession lost its way in terms of having influence and control over what it makes.

I made a key decision that the only way that I could personally improve that influence was to move up the chain to become a developer - that is, a client in my own right. I derive pleasure from the notion that development is an art and that if you want to get good buildings, you have to treat it as a creative process and find a creative route to making it. Our project management skills are more like design management; more collaborative. As such, we've always had a very interesting, robust collaboration working with architects like Matthew Wood, dRMM, Stephen Taylor, Meredith Bowles and most recently with AHMM - and engaging them in a creative process from the outset.

Of course, this comes from the background of architecture, but I'm now so embedded in the mechanisms of development: I believe that the only way a project is going to get better is if the client wants to make it better. The only reason the client will do that is if we determine the added value, which we begin to do at Solidspace. The work - the care, the thought, the time - that goes into our projects has to give it a financial benefit at the back-end, and that is the kind of premium that people are prepared to pay. So Gus's point about custom building is actually an incredibly interesting route that connects those two things together.

Allowing for choice

Roger: The reason lots of people shun new build is because the quality of housing produced by most housebuilders is so poor. People are voting with their feet and starting to say no. In this country you have a very limited supply of housing. You have the housebuilder, who has absolutely dominated - producing the 'bottom-end' in housebuilder parlance, right up to the top-end luxury level, often within the same company. The other side is social housing, which has its own set of problems. But we do desperately need a new kind of supply vehicle in this country and that's why I think custom-build is really interesting.

Templates of house design customised according to the Solidspace DNA, featuring split levels and basic function Courtesy Solidspace

Gus: Ultimately in the UK, you only really have three options. One: you can go and buy an existing house. which may not give you the desired standard of efficiency or comfort. If it's not right for you, then you have to make the necessary refurbishments. Two is to go down the self-build route, but as I mentioned earlier so few people can actually make it happen. And the third option is to go and buy a new build. And so I suppose we see custom-build as a kind of fourth way, for those people who normally would be able and willing to see how they might adapt something existing - in a way that's just a form of custom build. What we're saying is that you can make new builds better, by engaging with the customer at the very beginning of the process.

We're also working with different types of groups - people at the beginning of their professional lives, or indeed at the end of their careers. That's interesting because some people are saying, 'We're priced out of the housing market, can we come together to do something, and can you help us?' And then others are saying, 'Actually, we all want to come together to live in the same place and grow old together, and we want to help our kids. Can you help us to do that?'

There are so many varied needs that we have as a society, which are simply not being catered for in the prevalent model of a big developer buying a tract of land and building what they think will sell - in the end, people will buy it because they think they've got no choice.

Get off my land

Roger: I do feel that we have to separate the notion of production from the ownership of land. The danger is that we've already put those two things together. The Government might well wonder why, after various schemes and cash injections to support buyers, we aren't getting volume from the housebuilders? I would answer that it is not in their interests. A housebuilder's primary business plan is about land, acquired in large tracts. If there is an increased supply of cash, that's going to drive an increase in house prices; if I'm sitting on a land bank of 10,000 units, and there's an increase in house prices, why would I accelerate my programme of delivery? It's against my interests - if I hold back, I'm more likely to get an increased price.

Templates of house design customised according to the Solidspace DNA, featuring split levels and basic function Courtesy Solidspace

How do you then separate the ownership of land from the manufacture of housing? I think there's where the product then becomes important. This is being explored, for example, in things like prefabricated housing. If you bought a plot somewhere, you could find some 20 different prefab offers to put a house on that plot, from companies not interested in the ownership of your land but rather in the quality of that house. Both the American condominium and the co-operative model exist and thrive on similar ideas. You own shares and equity rather than land. The custom-build approach can create that deleveraged situation - which allows you as a producer to invest in the product itself. And that's all. You make sure that your product is attractive to your consumers; has all the capacity to vary what the consumers want; which is efficient, has a thermal capacity you want; is simple to manufacture - cheap to manufacture, so you can spend more money on space - all of the qualities you would expect any manufacturer to think about. Gus: The model has been around since the mid-19th century; building societies were set up as mutual funds on a similar basis. Some local authorities are really trying to work out how they can provide affordable housing, either through sweat equity or by keeping the land itself. So if you're commissioning the first home, the land is owned by a community land trust (CLT); you only have to pay for the product. So when it comes to sell it, you still only have to sell the product, the stuff that sits on top.

I was at a custom-build conference yesterday - the first one in the UK - and it was very interesting to find out that there are a few of us doing it now, and that every one is following slightly different routes. But ultimately what I like is that it's all about the customer, it's giving value to the customer in a way that speculative development does not.

David Kohn Architects

David Kohn

David Kohn is the founder of David Kohn Architects, a small, award-winning practice based in London. Projects include Sotheby's S | 2 space, Hackney Wick's creative hub The White Building, and most recently the Carrer Avinyó apartment in Barcelona.

During last year's Venice Architecture Biennale, DKA was invited by writer and curator Elias Redstone to think about the Argentinian model of 'fideicomiso' group building, a practice which has revivified following the financial crisis. Kohn has used his teaching platform to explore what such a model might mean in the UK.

David Kohn imagines a British version of the 'fidecomiso' collective-built apartment block Courtesy David Kohn Architects (DKA)

David Kohn: The practice has historically always been interested in building houses. Ever since our first house in Norfolk we've been trying to work out how you can scale up, from one home to many. But we are a small practice, interested in trying to retain a culture of searching and testing projects. And there are lots of people, established firms and markets who are doing standard, large volume housing schemes - and some of them do that quite well. We think we'd be better served by trying and think about how conventional models could be challenged.

We came across the research undertaken by the curator and writer Elias Redstone, who for his work on the Venice Biennale had been speaking to a firm in Buenos Aires called Adamo Faiden - I was already aware of its beautiful work. We learned about the Argentinian fideicomiso contract which had enabled it to build so much, even when it was such a young practice. Essentially, fideicomiso is a fiduciary agreement, which allows the architects to bring a group of clients to an investment proposal for a piece of land. The group employs the architect together and in return, each investor gets a unit according to their specification. The group pays the architect for the design and to administer all these relationships, but they do not need to pay a developer to take planning or market risks. It is worth noting that in Buenos Aires they have very simple planning guidance that makes it quite straightforward to buy a plot and then know exactly what you can build on it; it's a gridded city and there's a rule book, which does help a huge amount.

Experimental research

In response to these findings, we set up a research project at The CASS at London Metropolitan University, looking at what fideicomiso might mean for the UK - and also at all the existing ways that group custom-build might be realised. Our practice at DKA grew out of approaching collaborators through research, in a way to discuss potential projects or ways of working in a noncommercial context. In that way, you might be able to somehow explore risks that you wouldn't be able to try in a direct commission.

The unit within the architecture school acts like a sort of lab for experimentation. The people we tend to bring in are not only other architects or critics from other colleges, but also people from the industries that we are working with, and people who might be more like potential clients.

Procurement & choice diagram: standard cookie-cutter developments versus collective models Courtesy DKA

We had done some work for the Olympic Park Legacy Corporation (which became the London Legacy Development Corporation); we knew that it had historically advertised sites to have a custom-build component, and we knew that it had not delivered on that. So we asked it: 'Are you going to put your money where your mouth is, and could there be a scenario where we could explore the viability of those sites using custom build?' So over the course of the year, the students developed projects; we also went to Barcelona and found some ideas in the coherent, almost structuralist aesthetics in some of the housing projects there, which could work to give a place-identity to collective custom-build projects. Then we asked our students to go and find potential clients and negotiate.

Managing multiple clients

The idea is that rather than a kind of academic exercise, where professional architects talk to would-be architects about what architecture is, students would go and investigate talking to real clients and negotiate with them from the outset. Our work at DKA is very much driven by our clients; building this relationship is key to making business viable, so it seems odd that, at architecture school, the client is rarely even theorised.

Incremental development illustrating building phases Courtesy DKA /Robin Turner

In fact, we were trying to up the stakes in suggesting that in the future architects might be working on larger buildings with multiple clients. Architects in the UK are generally wary of being faced with many clients. Most architects in the UK are sole practitioners, building for one client per project. There's this idea of self-expression - and as Grand Designs tells you - of providing a dream. But how do you treat 10 people in that way? You can't; if you want to do group custom-build, you actually have to rethink what it means to be an architect. In the UK, group custom-build projects can take forever, because there's no vehicle for consensus on things that are necessarily shared.

If you look at these Argentinian models, the collective part - so the facade, the common areas, the structure - are super-simple and very consistent, even from building to building. So you see a lot of housing being built quickly, that looks very much like it is bene. tting from some kind of coherent overview - yet, it's full of individuals or families who have had in. uence from the outset.

Reality and risk

Applying the CASS research into reality, we've been speaking to clients who approach our practice with housing requirements and are amenable to the idea of having a . at in a collective building. So we're testing our version of . deicomiso, if you like. We are able to show them how far a certain amount would go in a scheme like this, and if you think about it, you're getting a new-build, to your speci. cations, in London. The cost for each individual client goes down; at a certain point you're exercising economies of scale through a pooling of their resources to employ you. The person who wanted us to . nd a site for their own house, get planning permission to build it, and employ us to build that one house, can now enjoy a house on that site for a sixth of the cost - if they're willing to co-invest with six other people.

Screen print made in collaboration with client, capturing a sense of desires and needs Courtesy DKA/Francesca White

Of course, it would not be like a conventional architect's appointment, so that's the bit we're trying to . gure out now; to develop a working legal model. Hopefully, that becomes something we can o. er to the profession, as a sort of protocol.

One of the main issues is managing risk. We want to remain a service provider, not a risk taker, so we have to allocate risk to each of the investors. Developers can take on risk; they spend their money to get you a plot of land with a house on it, and make money through passing that risk on to the buyer as a cost. Also, in the . deicomiso model at least, fees are paid in stages. Which means you can pull out at any point, and the other investors can buy your shares in the property. You don't want anyone to feel locked in, and you want the other investors to know that this model has su. cient . exibility so that it won't collapse.

Solving the bigger problem

My feeling is that this isn't a panacea by any means; the proportion of new homes that are self-build is only something like seven per cent to 12 per cent. However, to even change the UK ratio of volume housebuilders to group custom-build or self-build by even a few per cent would be well worth it. It might be in part the legacy of social housing, which has somehow fed into a slightly class-ridden idea of what it is to build at scale and to live that way. However, if you look at mansion blocks, dating from 50 years before the typical stigmatised council estates were built, you realise that 'collective living' was actually available to lots of di. erent economic groups, at varying levels of luxury or provision.

Adamo Faiden's Once building in Buenos Aires comprises six flexible units and a communal roof garden Photo credit: Cristobal Palma, Courtesy Adamo Faiden

We want to start where there is a realistic chance to actually deliver something through the opportunities presented to us. People do contact us because they love our design and because they'd like their own house. So through doing that, we can work out the hurdles of this sort of model. None of our current clients are the super-wealthy; professionals with families who would be owneroccupiers, not buying for investment. So if we work out that sort of model, it becomes possible to imagine what could happen if you're working with half the cost, or half the size. It is a conceivable hope that, as the model is repeated, then one could start to reduce the cost each time, even introducing possible funding models This would make it more a. ordable - eventually it could attract people who wouldn't come to us directly.

At this stage we're not approaching mass housing; we're looking at the scale of about . ve or six units on plot sizes that are perhaps too big for a single house, but too small to interest a developer. It might not happen, if the risks cannot be entirely mitigated. But rather than coming up with de. nitive answers, or a model where you just push a button and houses come . ying out of the other end, I think the way we'd hope to work, the way we enjoy working, is to constantly re. ne ideas, to keep working on it.

Collectivecustombuild.Org

Cany Ash

Cany Ash is a co founder, together with Robert Sakula, of Ash Sakula Architects, a small, imaginative, community-focused practice whose work has won a large number of RIBA awards as well as wide public acclaim. Cany has also worked for the Greater London Council (GLC) architects department and as a Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment (CABE) enabler. She worked through 2013 to investigate Collective Custom Build, stemming from a research initiative at Sheffield University, producing website collectivecustombuild.org

Cany Ash: The way that things like self-build are defined is obviously crucially important. For some, it can actually mean physically building things yourself, whereas for others it usually means self-procured. Some statistics are a little out of date when looking at how much self-procured stuff is built here as opposed to places like Austria, where we're talking about 80 per cent - and a lot depends on definitions, but in England, we're at around five per cent. It's only by adding Scotland and Northern Ireland that the UK reaches a 10 per cent to 12 per cent figure of self-build.

Beyond the house as a product

In his Sentences on the House, the architect John Hejduk thought about what the house means in an almost animate way; in the Middle Ages too, it was quite normal to speak about inanimate objects as having desires and preferences. These sorts of ideas are of course not talked about in the housing industry. It's a product: a market product, a financial product and a consumer product. Normally with consumer products, there is some choice. But instead, there has been reduction by more than 50 per cent of those housebuilders producing between one and 30 houses in this country.

The concerns of volume housebuilders, as rendered by Cany Ash Courtesy Ash Sakula

If you go back to this idea of the house as something beyond a market product, you could start to think of it more subjectively, as part of your personal story, part of your emotions. For most individuals, it is the biggest purchase you'll ever make, and it gets tied in with relationships and personal circumstances, ideas of permanence and commitment. And I guess the most powerful way of fostering good architecture and good communities - all that positive stuff - is for that connection to start quite early with the house. So if you're involved in designing it or building it, or if you're involved in a collective of people who are jointly moving forward with a plan to co-author some part of it, there's going to be a deeper idea of ownership.

Creative constraints

A huge amount of housing regulation - especially in volume house production - leads to crazy limitations and distortions, both in design and in procurement. These might produce houses that pass through building regulations, but they're not the only way of complying with them. Cutting away all of that and getting back to some of those qualities a house or a home is - what the joy might be, for example, in a circular route between a kitchen, bedroom and hall.

You're not left to explore these areas if you're buying 'off the shelf', or if you're an architect who is an expert in large-scale residential development, but used to paring things down to minimum floor areas rather than being creative within constraints.

Screenshots taken from collectivecustombuild.org, the information portal created by Cany Ash and colleagues Courtesy Ash Sakula

The publication of A Right to Build, by Alastair Parvin and 00:/, was a really good primer and catalyst for lots of things that need doing to develop the self-build sector. There are notions like of the consumer becoming a producer or pro-sumer through digital means that we can't anticipate yet. Combined with Kickstarter funding and the aggregation of demand, it seemed to suggest there would be a 'revolution' really quickly!

But those things are just a bit slower to take off, not least because of the super-conservative construction industry. The players who would be excited by those new possibilities might not have the means or confidence to explore those possibilities. The reason for doing our project is to move on from the slight sense of abstraction and idealism in that publication.

Making research useful

Our website Collective Custom Build is very much a tool for advocacy and a knowledge transfer project, which we have made in collaboration with Sheffield University - specifically Sam Brown, Christine Cerulli and Fionn Stevenson, who is about to replace Flora Samuel as head of the school of architecture there, as well as David Birkbeck from Design for Homes.

Screenshots taken from collectivecustombuild.org, the information portal created by Cany Ash and colleagues Courtesy Ash Sakula

Sheffield University invited us to pitch for a tranche of research money granted by AHRA (Architectural Humanities Research Association), to research self build. We, as Ash Sakula, were pitching against architecture 00:/, mae architects and others, working with academics and housing industry figures. The main idea we put forward was that this kind of research would only be useful if it could succeed in getting out there and really be a useful tool. So we said from the beginning that we would like to make a website - one with a number of ways into it, with layers of information. As an individual you can browse for facts; if you are an academic, or a group of people wanting to build up an amount of information over time, you would also find resources there to build an argument when you approach your local authority.

Our idea of collective custom-build - which is very loose, actually - doesn't involve actually living together; everyone has their own territory. We haven't been exploring co-housing that much. The hope is that the Collective Custom Build site is something that can be chatted about and consulted casually - that it remains undaunting - but that also becomes a really good, solid resource for people to make their own libraries. It's like a self-help, self-build library. There's lots of information out there but it's all diluted in different places, so the achievement has been in pulling it together, making it navigable and useful, to be able to present and use it to make an argument.

Housebuilders are doing a terrible job

The fact is the housebuilders are doing a terrible job. There is a target of 240,000 houses built each year, but at its peak in 2007 there were only 212,000 - we're building in this huge deficit. Housebuilders don't want to build too much because you have to show that your development is creating huge demand; it's how sales works. So rather than oversupply, you have to trickle them out. With self-build in the Seventies and Eighties, for example, you had people doing things on their own, and so couples would get divorced or you would run out of steam on a project, and that kind of fragile situation is probably what gave rise to the idea that there is more risk involved in self-build. But if the housebuilders are not delivering, then surely that's a risk too.

Screenshots taken from collectivecustombuild.org, the information portal created by Cany Ash and colleagues Courtesy Ash Sakula

But local authorities could really start releasing land to people who want to build maybe five, 10 or 15 houses, on crucial corners that can achieve good placemaking, which can give an area an identity. We've been talking to Leicester City Council, for example, which has given clearance and outline planning permission on sites for something like 3000 homes. For anyone to move on those sites, there are some 80 planning conditions, so you can only do it at scale - because no one person is going to be able to conduct the onerous environmental impact studies. The fact is if you've got huge sites - such as that one in Leicester - you could cut off a little bit of that land and let a group build 20 houses. But local authorities prefer the idea of doing one large deal rather than lots of little deals.

Targeting local authorities

Although we've put a lot of care into making the website accessible to all sorts of people, the main target audience was perhaps the local authorities-themselves. They have new powers and they can dispose of land, but they don't always have the confidence to take those steps. In the past, councils could not work with the private sector to sell off land; then gradually it became OK to talk to the 'good guys' who would address regeneration. This has been built up through public-private partnership models and as long there are enough Section 106 or CIL (Community Infrastructure Levy) agreements going back and forth, they can work positively.

Councils could be forgiven for feeling like these exchanges are the only cards they hold in their hands, the only way to move a community forward - to pay for stuff by leveraging against lucrative private development. But they're more powerful than they think they are, and could kill two birds with one stone; they've got people who need housing in their communities, there are problems with local employment, and a lot of land in holdings.

Screenshots taken from collectivecustombuild.org, the information portal created by Cany Ash and colleagues Courtesy Ash Sakula

We've been trying to work with city councils; we find that when it comes to anyone who isn't a large-scale volume housebuilder, they're not so comfortable. But it might be helpful for someone to see, on our website, the UK self-build compared with the provision from any single housebuilder. The total number of self-build matches those built by any individual large-scale housebuilder, which is quite encouraging.

Multi-level access

As with all good software, there are multiple ways to get into that sort of information on the website; there are curated headings of information, and then there are other routes to that content too. For example, if you watch the short introductory film on the home page of the website, there are themes which move along the bottom, and these themes relate to sets of documents on the right-hand side of the window - facts about the housing crisis, facts about local authority schemes and the NPPF (National Planning Policy Framework).

It's trying all the time to normalise the idea, to say 'No, actually it's quite sensible.' The idea is that through familiarity with the CoCuBuild resource, we can normalise and increase this sort of activity. The website or information from it can be sent to local authorities and taken in by groups that want to negotiate with them. If we can keep it up to date over the next few years - adding and subtracting content as things develop - then it becomes a way to make one's argument. It should enable people to point to evidence that actually central government is behind schemes like this, to say there is support in the NPPF, or to present that this is how they're doing it in Berlin, or Argentina. Even internally it's helpful for staff in council authorities to go back to their superiors and prove the point to them. So it's really about creating accessibility and agency at many levels.

Architecture of information

The guys who built this web 'infrastructure' - a group called Hush - did so for very little money, because they're going to use this multi-access model in other, commercial projects. The colour cartoons are mine, and the black and white drawings are done by some artist friends of mine in Berlin. We agreed that we'd have these two levels of drawings accompanied by this BBC voiceover, to give it a sort of approachable but authoritative feel - a little bit tongue-in-cheek, we hope.

Collective custom-build can catalyse and give identity to awkwardly located sites Courtesy Ash Sakula

For us as an architecture practice, the website has been an interesting place to be using one's talents, because you're more directly connected to users. It's been fantastic to be able to talk to people and hear about real needs, quite intimately - it's why we trained. We're quite good at scenario planning, of testing an idea and thinking about the extremes of how it can be played out. If we can imagine a new brand of architect who could be very people-based, like we are, who knew about planning, finance and legal routes, I think that could make me a better architect; I could learn more in the field and become more entrepreneurial as an agent in that field. But I'm not actually sure that's the same as investing what tiny bits of money one's own practice has in developing one structure or answer that cracks the nut.

Moving forward, it would be nice to think that the Homes and Communities Agency could take the lead on this sort of initiative. Local authorities - such as in Bristol, with architect George Ferguson at the helm - could also take these ideas on. That CIL has been removed from self-build projects is pretty encouraging; I guess it's a sign of central government's support of the industry, which this sector really needs, in order to become more and more confident. The problem is that you need a certain quantum of schemes that are very visible and successful to prove that it works, and to be honest, it's early days yet.

De Flat, Kleiburg

Kamiel Klaasse & Martijn Blom

In the Bijlmer Estate on the outskirts of Amsterdam, Kleiburg is one of the biggest apartment blocks in the Netherlands. As a remnant of 'obsolete' modernism, its story is comparable to that of London's Heygate or Robin Hood Gardens estates; despite its unique, quasi-brutal composition, it faced neglect and ultimately, demolition. That is, until planner-strategist Martijn Blom bought the rights to develop Kleiburg for less than a song, and together with NL Architects' Kamiel Klaasse, devised a DIY self-build strategy to give the building a new lease of life.

Kamiel Klaasse: Martijn started working the whole project with a developer, who has much more muscle power and money, basically. They formed a consortium, proposing this fairly new type of project: not a completed renovation but an opportunity of making your own apartment according to your wishes. They also made a plan within their development framework to renovate the common spaces of the building.

The Kleiburg block on the Bijlmer housing estate; reminiscent of Sheffield's Park Hill Courtesy NL Architects

Martijn Blom: The project was made possible by the decision of the housing corporation to devalue the building in a way to €1 (84p). That's 500 flats for one euro, as well as the land lease to the municipality, of course. The municipality owns the land and we have a long-term lease construction for 44 years, which is generally the situation across Amsterdam. The low acquisition price meant that we could invest more in the plan. Our consortium immediately produced a booklet of DIY housing, and we had to make a proposal for securities, schedule, mortgage options, financing models for the project itself and so on. The basis for renovation was a property investment project; the focus on the people who would live there comes after that. Of course we could not market the DIY self-build idea until we had all that stuff worked out.

Obsolete typologies

Klaasse: I think the housing association that owned the Kleiburg building actually hated it; before the Lehman Brothers crash of 2008 changed everything, it had hoped to demolish it and build new low-rise apartments - as has happened across the rest of the Bijlmer estate. The general notion, even from some figures in the Government, was that this sort of building could not be a successful typology any more, that people wouldn't like to live that way anymore. Systemic neglect, to the point of dereliction, had allowed the owner to claim that costs were too high to even renovate; in a way they had made it so derelict to even renovate. Of course, there was another force resisting this: people who live in the area were quite fond of the building, and other heritage fans who respected this urban ensemble and its unique geometry-because it is a beautiful composition. If you remove Kleiburg, one of the last untouched examples of its kind, you'd really be getting rid of a significant piece of heritage.

Kleiburg's brutal slab is located in lush parklands, adjacent to a lake and an elevated train track Courtesy NL Architects

Blom: The building was advertised in December 2010, in January 2011 we started to formulate our bid; the selection process was in June. And then negotiations on the plan started in December until September the following year, when we could begin the project in earnest, though we had done a little bit of promotion before that, even though we had not signed a contract. Formal marketing started in November 2012, and then in March 2013, the first house owners started to sign their leases. By May, we were already at 70 per cent - 70 of the initial 100 apartments finding tenants. So now contractors are working on the basic renovation of the building and they are scheduled to be finished early this year, when people can start coming in and taking over, making the changes they want.

Collaborative practice

Klaasse So although the housing corporation wanted to get rid of it, it was forced somehow by media and other pressures to give one last push, to see if there was any possible way to rescue it. So it generously advertised this scheme where you could obtain the building for €1, if you could propose a working, feasible business model, and of course they received a lot of proposals.

Open workshops explore possible apartment types in De Flat, the regeneration scheme for Kleiburg Courtesy De Flat./Martijn Blom

Four proposals were selected for further development, including the self-build pitch made by Martijn's consortium - and at that point we were not part of that at all. Then the area supervisor - whose position is probably the most beautiful cog in the Dutch planning system machine, to resist the pressure from the market to roll out banal proposals - this guy thought Martijn's plan was really solid, but he suggested that NL Architects came on board to give a little more concern to the existing building and the final aesthetics.

Martijn had proposed sweeping balconies and things that would have altered the facade and the look of the building. When we came on board, we were able to save it a lot of money by saying that we think the building was fine as it is; it just needed a little help to look more like itself, in a way. We were really excited to be involved in this process.

Blom: In essence, I act as a consultant for architects and for planning, making property plans for the cultural sector and commercial estates. The initiation of a development project is not easy these days. But it's doable if you have a great idea. And a great team, so we had Kamiel as well as the three partners on the consortium; each person has their area of expertise. Kamiel and NL Architects came on board in June of 2011. Then negotiations on the plan started in December until September the following year.

Long-term interests

Klaasse: Actually we'd been thinking about it for a while. In the mid-Nineties, when this area started to be regenerated and developments started appearing, we tried to submit some proposals in order to change public opinion. Architects don't usually have too many opportunities to address the public, but in that case we were given the opportunity to take over some billboards, and so we took that opportunity to heighten awareness about the existing qualities of the area, which were not so bad after all. We wanted to suggest that, if you paid a bit of care and attention to the existing materials, maybe people would appreciate them more. That was a very long time ago, but it was aimed at opening the eyes of the public to the intrinsic beauty of the place as it is.

Klaasse hopes that options offered for the communal deck areas will encourage social exchange Courtesy NL Architects

Of course, we were not successful and by and large the demolition party started. But 15 years later when we saw this Kleiburg situation unfolding, we saw the opportunity to use our blog to vocalise the same idea. Before we were invited on to Martijn's plan, the only response we had was to make a mash-up of a magazine - we put Kleiburg on the cover. It's completely false of course, but the idea was to suggest that if you hit the right momentum, many people would start to see the building's potential. That showed our belief in this building, and that it was just a matter of time before people would see its beauty.

Structurally the building is sound, and I think it's beautiful; the way that it embraces the landscape is probably its best feature. You have to understand that as soon as you make this dense carpet of low-rise buildings, you would destroy the greenery and park landscape that sits underneath, something which has happened elsewhere in the area. The slogan we came up with against this demolition was to say: 'What use is a vista if you are short-sighted?'

Like-minded freaks

Klaasse: Of course, the risk we took for the development and for Martijn's consortium was the hope that enough people would see the same beauty that we did, in this high-modern, early brutalist kind of aesthetic. We might have been freaks who just loved Kleiburg for its historical value - but apparently not, as it seems to be quite popular. I actually think that this attitude towards the old materials is strongest in London - you have these wonderful Lasdun buildings, and things like the Trellick Tower. The big advantage of those examples is that they are very well-placed in the urban fabric; with Kleiburg it's a slightly different story, because the Bijlmer estate is in more of a suburban neighbourhood. A typical suburb is low-rise; when people choose to live there, they expect a garden and a place to park. We were suggesting a more urban way of living in a suburban setting.

Various public events have attempted to change the way the neglected block is perceived Courtesy De Flat/Martijn Blom

So our part in the proposal, on an aesthetic level, was to suggest that we return the building to its original beauty; to expose the beautiful concrete and the hardwood details as they are. There is a big trend in the market embracing this 'all natural' aspect; you see it in food, for example, where there is an interest in rawness or roughness, which is perfectly in sync with our intentions. So we wanted to leave the original building as intact as possible, and looking more like itself; all the earlier proposals that we had seen were concerned with changing the way it looks. The consortium took a little convincing, as did certain figures in government, but they were soon on board - not least because it saved a lot of money.

Blom: There was a precedent for this self-build-led regeneration in Rotterdam; in order to develop a certain area, there was a similar offer to buy cheap houses that allowed people to invest themselves - to base the project on the energy of the people. That was very experimental, but quite successful. This project was well-known, and we thought about whether we could transfer this idea to Kleiburg as De Flat. We didn't apply the self-build idea to the outer facade or to building free-form architecture, the wild housing concepts of 10 years ago - like you had in Almere - with no municipal oversight. The trick in our case was that you lower investment by using the DIY system, and at the same time you introduce the concept of freedom to the buyer right from the start. And of course the other attractive thing is the affordable price; it's a low-cost model so it's suitable for starter homes, at a time when it's difficult to buy a property. Community and transparency

Klaasse: We thought the building looks quite abstract, maybe one of the most abstract in the Netherlands. It doesn't have any 'buttons' on it. It has a kind of Dieter Rams aesthetic. So we thought if people are enjoying this kind of smooth, button-free 'Apple' design, maybe we should work on customising the interface. We approached the interface as if it was that second skin, the actual walls of the flat which open on to the public galleries and walkways. These interfaces between inside and outside were a little defensive originally; the windows were small and set above opaque panels for privacy. We decided that it would be better to open this up, to expose the diversity of interior configuration and create more porosity through the views of the building from front to back.

Tetris-like painted panels on the outside of Kleiburg demonstrate internal possibilities within the block Courtesy De Flat/Martijn Blom

We decided to remove all those opaque panels and to introduce new facade elements such as sliding doors and set-backs, allowing people to modulate this interface. In the apartment block where I live we have colonised the gallery outside - my kids grow their vegetables there, we've placed a bench where we have breakfast and it's a wonderful extension to our home. The hypothesis is that it fosters a sense of community through the way you use that space, and it might actually work this time because the people taking up this scheme are so motivated and eager to make it work. My guess is that most of them will stick to the layouts we have advised. The main apartment size is 100 sq m but there are smaller units too, which are really popular. In the structure, you can join units laterally or vertically - I am pleased to see that some people are doing what we hoped and interpreting the inside - taking two or three units and thinking about creative ways to integrate them. The colourful Tetris-like billboard effect was just to demonstrate what could be done on the inside. Structurally there are a few constraints; knocking through and joining flats would work better on the upper levels, and things like openings in the floors must be carefully coordinated by the consortium - it's not a Wild West situation.

Blom: The response we're getting is mainly from the greater Amsterdam area; these people know a bit about urban life and are more relaxed about living this way. They can see past the sometimes negative image that the Bijlmer estate has, through to its positive future. However we are getting people from the south of the Netherlands, and families too. By May 2013, we had already filled 70 of the initial 100 apartments. Now contractors are working on the basic renovation of the building and the first phase is scheduled to be finished in January or February: then people can start coming in and taking over, making the changes they want. The consortium oversees the work, but we can also provide support in terms of logistics, of arranging social controls, like not building all night, but basically enabling this freedom.

NL Architects' founder Kamiel Klaasse identifies the Klieburg's relationship with its landscape as a crucial advantage Courtesy NL Architects

Hope and glory Blom: In essence I consult for architects and developers, making property plans for the cultural and commercial sectors. The initiation of plans, in collaboration with others, came to be something that I enjoyed, though initiating a development project is not easy these days. It's possible if you have a great idea and a great team, and we had Kamiel as well as the partners on the consortium.

The project is an investment opportunity, but it comes at the right time to address the city's housing situation. Property prices in Amsterdam are too high and it's not easy to find a house. There are some opportunities like this, where owners are devaluing and releasing building stock.

Klaasse: There is a tendency to vaunt the most technically 'sustainable' building - but new builds often leave a lot of space unused and old buildings remain neglected. I think it's a good idea to see what you can do with existing structures before you tear them down; they have some qualities that are hard to beat. In this case I think it's a really beautiful and generous offer we're making: you can own a place in this beautiful shell, but you can make it yourself and create a range of opportunities. At this time of crisis, the possibility of owning your own property and being able to do what you want with it is really attractive. It's about bringing the building back to its former glory, but also a new way of looking at property.