Drawing architecture in motion

Artist-in-residence at the British Museum, Liam O’Connor has been hiding away inside for the past three years while Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners’ new extension went up around him, documenting its construction in drawings. He tells us about his practice, while Graham Stirk of RSH+P relays observations from the building process.

Words Shumi Bose

Drawings Liam O'Connor

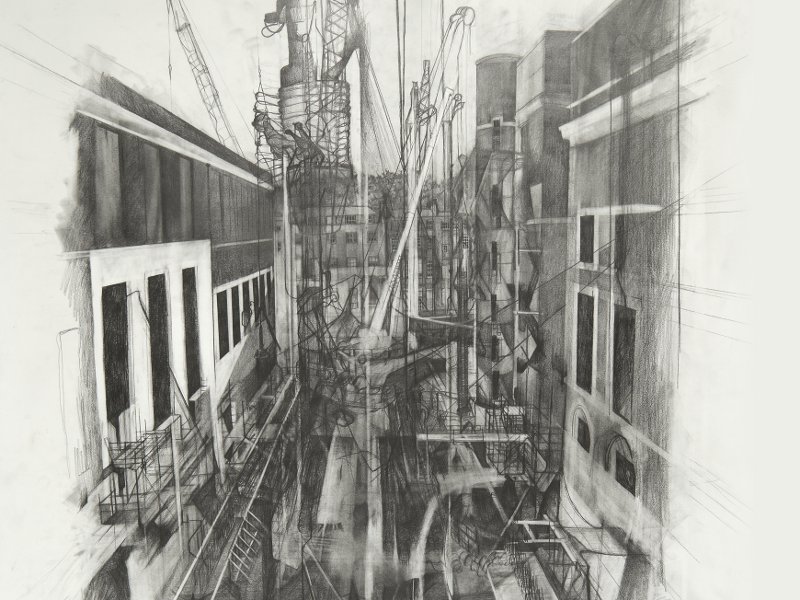

As artist-in-residence at the British Museum, Liam O'Connor's hide-like room has perched at the edge of a building site for the past three years. The World Conservation and Exhibitions Centre -- a new extension to the British Museum designed by Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners -- which opened this spring. O'Connor has been documenting its construction, since construction began in 2010. After a long process of scrutiny and an almost physical, Stendahl-like relationship with the site, O'Connor's 'final' piece is a single drawing recording many layers of observation and study, made over many months -- first recording the voided site, then the turbulence of excavation, later the imposition of structural steels and the reorganisation of the space.

O'Connor's drawings show a layering of graphite as well as narrative; early earth movements are visible underneath the later scaffolding structures

In the act of building the world around us, the drawing is the first site of construction. In the 16th century, Renaissance humanist Leon Battista Alberti championed the architect as an intellectual professional, and the drawing as the architect's original act of creation. So emerges the claim of drawing as a fundamental practice of architecture: still today, through the complex process of producing a building, the drawing remains the architect's space for exploration and expression.

O'Connor's drawings show a layering of graphite as well as narrative; early earth movements are visible underneath the later scaffolding structures

Trained as a graphic designer, O'Connor cites summer jobs labouring on building sites as having a profound impact on his working methods. Indeed, as spectacular as his layered pencil drawing is in documenting RSH+P's museum extension, much of his drawing research at the British Museum allows the site to 'record' itself on paper -- almost casting the site as the author. O'Connor has gathered marks, rubbings and textures made from the building materials and process of construction -- like the arc of a digger, or the rust marks left by iron nails -- that produce some of the most moving works.

O'Connor's drawings show a layering of graphite as well as narrative; early earth movements are visible underneath the later scaffolding structures

The carpenter's bench is a ubiquitous structure on building sites: this unromantic object supports everything that is measured and built there; its surface recording innumerable saw-cuts and tool-traces. It is in itself a drawing, and every physical process ingrained on its surface exists somewhere in the building. O'Connor allows these otherwise mute elements to speak through the marks they make; as well as observing and documenting the changing construction site, he records the physical traces of the site itself. During his MA studies, which he completed at the Royal College of Art, O'Connor settled on architectural and urban spaces as the subject of his experimental reportage drawing spaces.

Site drawings, made by the construction activities. O'Connor made rubbings from an ordinary carpenter's bench richly etched with repeated cuts, and collected rust marks from discarded iron nails

Mainly narrative significance and composition, he noticed that these 'concrete' spaces were also in flux. Drawing a set of stairs in King's Cross, he returned to find these filled in: they had disappeared and were no longer available to use or view.

Site drawings, made by the construction activities. O'Connor made rubbings from an ordinary carpenter's bench richly etched with repeated cuts, and collected rust marks from discarded iron nails

Something seemed significant in drawing these precarious places; O'Connor's work thereafter takes on an almost documentary, albeit subjective, fervour -- reconciling the artist with alterations in the perceived world.

Site drawings, made by the construction activities. O'Connor made rubbings from an ordinary carpenter's bench richly etched with repeated cuts, and collected rust marks from discarded iron nails

O'Connor works strictly from observation, positioning his work from the real rather than remembered or imagined space. But although they observe the present moment, O'Connor maintains that his drawings are made in relation to a site's past, which is always present and must make itself known. Seeing the city fabric as a dynamic process rather than a fixed entity has informed his choice of charcoal and vivid pastel, capturing something of this fluidity.

Site drawings, made by the construction activities. O'Connor made rubbings from an ordinary carpenter's bench richly etched with repeated cuts, and collected rust marks from discarded iron nails

According to Austin Williams, who convened the drawing workshop Paper Salon, in conjunction with the British Council, 'Many people have reverted to a leaded pencil on lined paper, to return to the skilful artistry that has been lost to the ubiquity of the PC,' suggesting that hand drawing 'requires swaggering in the face of incipient failure'. Indeed the physical act of drawing has an immediacy to it; the drawing or sketch becomes a critical tool for experimenting, making mistakes and suggesting possible solutions, rather than the careful modelling of photo-real alternative realities.

Perhaps our increased exposure to visual imagery in general, through our screen-dominated lives, makes us more sensitive to the specific qualities of hand drawing -- expressive, humane, suggesting a dynamic space of possibility. O'Connor's documentary drawings of the built environment bear repeated viewing, telling stories over time that would otherwise be forgotten.

Site drawings, made by the construction activities. O'Connor made rubbings from an ordinary carpenter's bench richly etched with repeated cuts, and collected rust marks from discarded iron nails

'It's interesting that someone takes an interest in process,' says Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners' Graham Stirk, of Liam O'Connor's documentation of the RSH+P extension to the British Museum. 'Our society doesn't often value that; it's about end-product and image.' Indeed the construction of the stateof- the-art World Conservation and Exhibitions Centre, which opened in March, has been a long journey, beginning in 2007. Stirk shudders to recall the arduous planning process for work on the Grade I listed Edwardian buildings designed by Sir Robert Smirke, in an area where 'people want no change'. Project architect John McElgunn adds: 'In the Square Mile, people expect building of this sort, but in Georgian Bloomsbury, they tend to want things to look a bit Georgian.' Perhaps what saved the £135m project was an abstinence from the flashy moves so typical of cultural buildings. The WCEC was trying to solve complex logistical problems crucial to the British Museum's ability to function as a world-class facility.

Exterior elevation of the almost completed World Conservation and Exhibition Centre, which Stirk describes as a lantern-like pavilion.

Photo Credit:Paul Raftery

As one of Britain's best-loved and most-visited places of interest, the museum's visitor numbers top six million a year. Though the queues snaked right around the block in 1972 for the famous Treasures of Tutankhamun show, the museum would have struggled to put on such an exhibition again, not least because it lacked an ample and dedicated loading bay.

Despite the conservative building guidance for historic Bloomsbury, RSH+P took the decision to stick to their modern guns with the WCEC. Photo Credit:Paul Raftery

'It's almost unthinkable to move priceless historic objects around this way,' gasps Stirk. 'Shuffling past the public, up flights of stairs and bumping into the Reading Room.' The new addition allows precious artefacts to be brought into the building with the necessary insurance safeguards, without leaving the special conditions needed to protect fragile items and, consequently, allowing the museum collectors and curators greater freedom.

The first exhibition at the new WCEC is Vikings: Life and Legend including this 37m longboat, which could not have been shown before. Photo: Paul Raftery

The challenge was in trying to tie all of the modern requirements of such a project into the middle of a Georgian- Edwardian building patchwork. The WCEC drops on to an awkward T-shaped hole, between historic buildings whose floor levels and plans don't match up. RSH+P has placed archive storage underground, where climactic conditions are more easily stabilised, while visitor and conservation study areas benefit from natural lighting.

One primary and visitor-facing requirement was a vast, column-free exhibition space at the same level as the Great Court. This was conceived as a blank and adaptable box, which might be changed according the narrative required of any specific exhibition. The first event in this space is the spectacular Vikings: Life and Legend (until 22 June), which includes the 37m Viking longship Roskilde VI, never before seen in Britain.

The interior of RSH+P's new extension to the British Museum uses transparency to improve working conditions for conservation workers, and pique visitor curiosity. Photo Credit:Paul Raftery.

'It took us a long time to develop the architectural language, and saw us moving into new territories of understanding materials and surfaces,' says Stirk. The main materials on view are heavyweight, construction-grade glass planks -- 'a veil between new and old buildings' -- and non-structural stone 'blades', which retains a relationship with the traditional Portland limestone elsewhere in the museum. The prevalence of structural glass keeps a certain amount of transparency between conservation activity and gallery spaces, piquing visitor interest.

As an object, the WCEC is intended as a series of lightweight planes; a supporting act to the existing museum, rather than a brash new hero or stylised neoclassical pastiche. Indeed, the WCEC doesn't even have a major new entrance because, as Stirk says: 'This is part of the existing museum; why on earth would we try to compete with that?' Instead the extension will be accessed through the Great Court, the museum's major hub.

The complexity of a project is often lost in the glossy final image. In Liam O'Connor's drawings, says Stirk, 'There's an archaeological sense as well as one of frozen energy -- it's almost like you can see ghosts of activity, capturing fragments that are disappearing.' The new facilities and display space will allow the museum to retain and celebrate cultural history from all over the world, which is what it does best.