Brief encounters: Crafts Council Collect

Veronica Simpson calls into the Crafts Council’s show, Collect, and sees much to celebrate in the cross-disciplinary, collaborative and confident spirit exhibited there

Words by Veronica Simpson

The last time I went to the Crafts Council’s high-end annual exhibition Collect, in spring 2017, the world seemed to have shifted on to a very worrying new axis: the era of Brexit, Trump, and fake news. I prowled the aisles marvelling at the extraordinary artistry assembled by galleries from all over the world, but also sickened by the idea that there are people out there who may think nothing of spending £3,000 on a silver milk jug. It seemed representative of everything that was wrong about our societal priorities.

Fast-forward two years, and the world certainly doesn’t seem any kinder, nor any more egalitarian. Probably the opposite is true. But I have also spent the past two years increasingly invited to comment on the contemporary art world; after two decades of writing about design and architecture – disciplines where original intentions are so often undermined or entirely derailed by pragmatics, policy, client dynamics or commercial necessities – it has been a liberation as a writer, arts lover and thinker to experience this alternative universe, where anything is possible and imagination (without legislation) can take you places aesthetically, emotionally and topically, that design and architecture can only dream of.

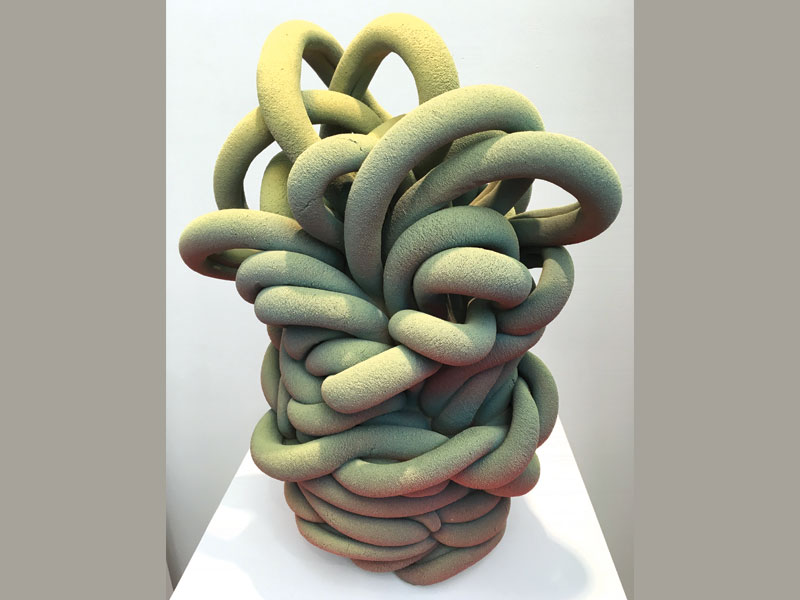

Waiting for Godot, by Korean ceramic artist Bae Se-Jin. Credit: Veronica Simpson

But the kinds of sums asked for the works I get to look at are also out of this world. If Martin Creed (or, to be accurate, his gallery) can charge £150,000 for a felt-tip drawing he knocked up in an afternoon, why on earth shouldn’t a master silversmith who has spent decades honing their skills, get £1,500 (after the gallerist takes their 50 per cent) for a thing that will possibly bring joy to your afternoon cuppa on a daily basis?

Other evolutions in the wider world over the past two years include the ongoing dissolving of silos between disciplines. We certainly seem to have bridged the chasm that separated art from craft. Among the 400 artists and 40 international galleries at this year’s Collect there was consummate skill and craftsmanship, yes. But a significant amount of work was also provocative and surprising, interrogating our relationship to materials and subjects; in their treatment of texture and form, they found ways to confound and subvert, to disturb and seduce.

Take the extraordinary, writhing creations of Claire Lindner: like mutant, multilimbed octopi, their matt, minutely pimpled surfaces looked soft, tactile, alive – nothing like the ceramic stoneware they were made from. There was some exciting blending of materials, such as Veneto-based alcarol Studio’s stools: using great chunks of gnarly Acacia wood, their crumbling, mossy exteriors were set in smooth, clear resin to preserve them but also give a surreal underwater appearance. Taiwanese/Italian duo and RCA graduates Vezzini & Chen, whose pieces combine handblown glass with ceramics, had conjured seacreature- like lamps with bulbs that glowed cloudy white against a translucent bowl.

Seven Stages of Degradation, from Sophie Thomas and Louis Thompson. Ester Segarra

Pushing materials beyond traditional forms, Peter Collingwood’s ‘macrogauze’ weavings were almost more shadow than substance: fragile structures of linen, with steel rods to support their intriguing geometries, they would enrich any wall or corner with their quiet beauty, as would Andrea Walsh’s ‘contained boxes’: small cast-glass sarcophagi, they housed smooth, pebble-like, fine bone china and gold or platinum boxes.

As I wandered the three floors of the Saatchi gallery, the cumulative effect of this carefully curated display of colour, material, texture and sensibility was intoxicating. But true art, as educationalist and activist César A Cruz has said, should ‘comfort the disturbed and disturb the comfortable’. While there was much to delight, there were also exhibits which carried with them some existential, philosophical substance, such as Korean ceramic artist Bae Se-Jin’s literary-themed Waiting for Godot work: two pale, timeless vessels, he had marked each tiny unglazed brick used in their construction to indicate the days, hours and months the piece had taken; a process of patience, boredom (undoubtedly) and forbearance of which Samuel Becket would surely have approved.

There was further food for thought on the top floor, where Collect Open presented more knotty, experimental and environmentally aware works, such as the collaboration between critical designer Sophie Thomas and glassblower Louis Thompson. Seven Stages of Degradation is a chandelier comprising hyperreal, crumpled hand-blown glass bottles filled with ocean plastic. There was also a welcome sighting of work by bookbinder Tracey Rowledge and silversmith David Clarke, with the next evolution of Shelved, featured in this column in 2018. Called Room, it combines the Shelved work’s punched postcard pieces and the pewter-coated figurines (perched on top of stained and genuine art-studio jam jars but protected under museum glass jars) to conjure a room without walls that invites us to reflect on the meaning and legacy of what we value, what we collect and why.