Brief Encounters: Amsterdam’s Print Art

Veronica Simpson is in Amsterdam, where she examines a social revolution of a 100 years ago...that of print art.

Right now, it seems we can’t move for exhibitions, TV shows, films, literature and news stories that flag up the thrills and spills resulting from the percolation of technology into every aspect of our lives.

With exhibitions the saturation is intense, with London’s show Robots breaking records at the Science Museum, Germany’s excellent and thought-provoking Hello Robot at the Vitra Design Museum and the atmospheric All Watched over by Machines of Loving Grace at Paris’s Palais de Tokyo. For lovers of fiction, Dave Eggers’ The Circle has been top of the bestseller charts – a chilling but exhilarating ride into the dark heart of a Google-like cult.

As for world news stories, surely the revelation that a tech Machiavelli has been harvesting information to identify ‘swing’ voters and then manipulating their social media to engineer both the Brexit vote and Donald Trump’s election is enough to cause a huge protest against the evident invasion of privacy (though don’t hold your breath).

In that climate, it was something of a relief to head to Amsterdam’s Van Gogh Museum in early March and an exhibition celebrating something utterly analogue: the explosion of print art that took place in Paris around the 1900s. At this point, as the Van Gogh Museum’s director Axel Ruger says: ‘Paris was the artistic capital of the world.’

Writers, poets, philosophers, artists, architects, were all congregating in Paris to experiment with new ideas of ‘modernity’, and print was the mass media of the day. Spearheaded by artists such as Henri de Toulouse Lautrec, Théophile Steinlen and Pierre Bonnard, with their passion for capturing the city in all its grit and glory – its landscapes, and the lives of ordinary citizens in the bars, theatres and streets of Paris – a movement was born that inspired many of the most innovative and brilliant artists of the day to seize the potential in this bold, expressive and economical medium.

And this ‘movement’ translated across all social and media hierarchies: the same artists who produced posters advertising cabarets, liqueurs, inks or theatre shows were courted by the fashionable classes to make vibrant artworks for their homes; ‘From the salon to the street’ is the exhibition’s apt strapline.

Curator Fleur Roos Rosa de Carvalho suggests that the kind of language we recognise in today’s advertising was evolved in this heady time of experimentation. She says: ‘We think life is fast now, but they thought life was very fast then, and you only had a few seconds to draw the attention of the passer-by. They did this by using a very strong visual language, strong colours, and typography.’

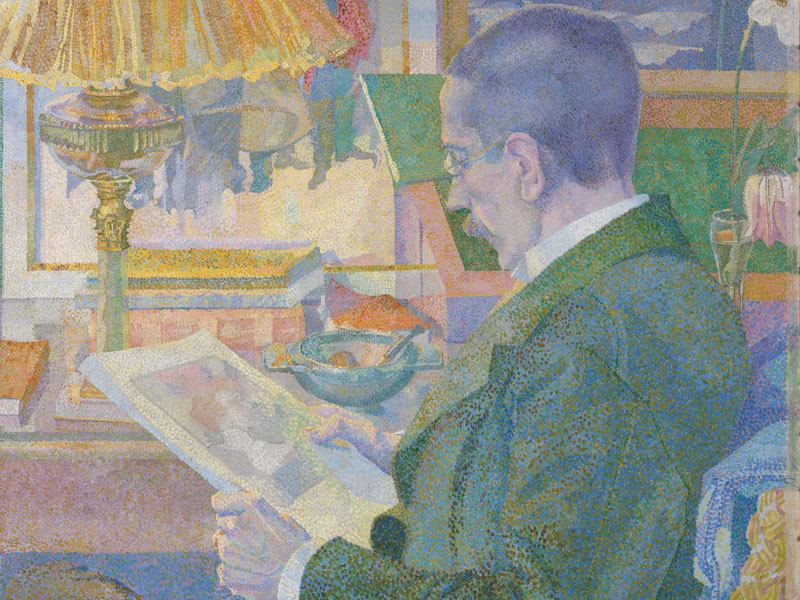

This was cutting-edge communication in its day, reviving the ancient arts of woodcut and etching with new subject matter, while the more fluid manipulations allowed by lithographic printing were giving artists a whole new print language. According to curator de Carvalho, it was this vibrant Paris print scene that first attracted Picasso to the city. The ease and economy with which artists could create pictures of street life, of prostitutes and urchins, of moments of intimacy and private reflection that would never have found their way into paintings (some of the more ‘intimate’ prints displayed in the show, including one by Edgar Degas, would have been far too risqué to go on public display), made for a heady creative atmosphere.

The exhibition departs from the usual neutral gallery setting to create a series of atmospheric, albeit occasionally clunky, room sets (from designer Maarten Spruyt), to highlight the way these prints were consumed, both on the street and in the salon of the private collector. We are shown a particular sequence, or ‘suite’ made for a private collection by Albert Bernard. It’s a moral tale of a young woman who is wooed and married, gives birth (something no painter has ever tried to depict in oils), enjoys motherhood, loses her husband, then is seduced, rendered penniless and dies.

As de Carvalho says: ‘It’s the kind of drama you might watch on Netflix today, but all created for the client’s private enjoyment.’

Art posters on show at the Prints in Paris exhibition, Amsterdam until 11 June

Art posters on show at the Prints in Paris exhibition, Amsterdam until 11 June

From intimate collections to series from up-and-coming new artists, the aspirational Parisian home-owner would have kept their own print collection in beautifully decorated leather portfolios, or locked away in their own private carved-wood library (there are handsome examples of these in the show).

After a hard day at work (in the bank, or the legal office, say), they would relax in the evening and look through their print portfolio, says de Carvalho, taking out each print for contemplation, or to share with discerning friends – consuming their visual stimuli in a wholly different, far more tactile and direct manner to the art that hung, framed, on their walls.

Could we compare such behaviour with today’s tendency to scroll restlessly – and share – through our Facebook or Instagram feeds the things that we and our friends find inspiring, whenever a spare moment arises? Perhaps, but where a print might offer a moment of quiet contemplation and restoration, social media’s hijacking by the self-obsessed and socially insecure infuses it with a whole different vibe.

Prints and posters were certainly the social media of their day: they had the power to turn their subjects into celebrities: for example, Aristide Bruant, now famous as the man in the red scarf and black cape immortalised by Toulouse Lautrec, allegedly complained that he was recognised everywhere thanks to the fame of this poster; though that didn’t stop him from once allegedly performing with replicas of the image either side of him.

Either way, it’s great to see a celebration of the graphic arts and the power of print – a medium also undergoing something of a revival. The British Museum is currently showing a spectacular collection of pop art prints – The American Dream: pop to the present – which features bold graphic treatments courtesy of Philip Simpson Design (yep, some relation, if you’ll forgive the plug).

But if your budget can’t run to a Warhol or a Steinlein, you might just catch London’s Original Print Fair, where you could snap up something possibly as profound, but just as enduring and a lot cheaper.