Blueprint innovation: Engineers + Architects

Innovative design and computational technologies have helped to generate a far more collaborative and mutually enriching way of working between architects and engineers. Zaha Hadid director Patrik Schumacher and BuroHappold’s Wolf Mangelsdorf invite us in on a conversation charting this evolutionary trajectory

Words Veronica Simpson

Technology has a tendency to lead us into realms we could rarely have envisaged. Once architecture was all about drawing boards and draughtsmanship and engineering was all about the purity of a complex calculation (which may have taken three days to compute), and little sympathy or understanding was shared between these disciplines. Now the crossovers between design and engineering technologies have opened up hitherto inconceivable opportunities for dialogue and collaboration between architects and engineers, and given rise to new forms of materiality, structure, aesthetics and building performance.

At the forefront of this evolution is Zaha Hadid Architects, and BuroHappold has been one of its longest-standing engineering partners in structural experimentation.

It should be no surprise that Hadid was able to embrace the kind of mathematical complexity required to push what might previously have been thought possible with the geometries of her buildings - after all, her first degree was in mathematics.

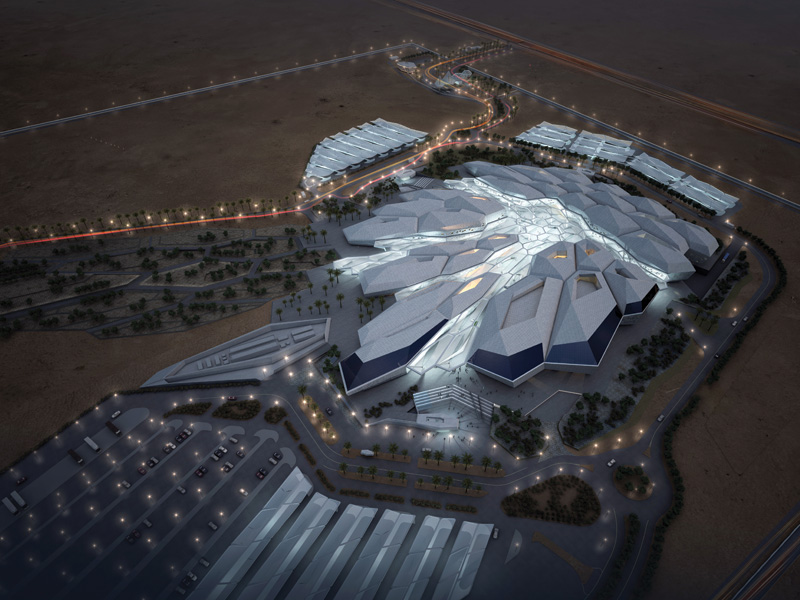

The King Abdullah Petroleum Studies and Research Centre, Riyadh, designed by ZHA

But BuroHappold’s ebullient director and engineering evangelist, Wolf Mangelsdorf, thinks it was Hadid’s approach to collaboration that lit the spark for this cross-fertilisation, as much as her gift for calculus.

Mangelsdorf says: ‘Zaha and Patrik [Schumacher, director] always appreciated that great work like they are doing cannot be done without engineers. With them, there has always been a big appreciation of the engineer, and a very collaborative spirit.

I would put architects in two categories: those who go: “This is what I want. Just make it work.” To them, I usually say: “Here’s someone else’s number; there are plenty of engineers who are really happy to do that.” And there’s a smaller number of architects who really want to work with creative engineers.’

Views of the King Abdullah Petroleum Studies and Research Centre

Views of the King Abdullah Petroleum Studies and Research Centre

For engineers with a strong streak of inventiveness, Hadid’s challenging geometries have always been exciting. Mangelsdorf says: ‘Even her early stuff is highly complex. To think that through you have to have the right wiring.’

Engineers were, in fact, key among Hadid’s early supporters. In her excellent BBC Radio 4 Desert Island Discs interview with Kirsty Young last February she said: ‘As an architect you need to understand the logic of engineering. I didn’t know that in the beginning. I used to like buildings [that looked like they were] floating, but I know they can’t float. Now I might want to make the building look light… [as if it’s] floating. That’s different. You devise a method of making a very light way of landing, so the engineers have to sort out how that’s done.’

Wolf Mangelsdorf, of BuroHappold. Photo: Zaha Hadid architects

Wolf Mangelsdorf, of BuroHappold. Photo: Zaha Hadid architects

But it takes a particular kind of engineer to want to make these shapes happen, Mangelsdorf agrees. He says that in the early days ‘I think engineers just didn’t know what to do with it.

You cannot get this stuff out of a text book. You have to take your text book and completely reinterpret it. That’s the challenge. This is not the sort of thing you do if you want an easy life. And for us, there is actually a big challenge in this. But I hate nothing more than getting bored. With Zaha’s buildings, I will never get bored.

There is this challenge of making the two things work together and develop forms that are challenging perceptions. That’s what Zaha is all about. She created a culture of experimentation. People have become much more daring because of her.’

Patrik Schumacher, director at ZHA Photo: Zaha Hadid architects

Patrik Schumacher, director at ZHA Photo: Zaha Hadid architects

A few months prior to this conversation with Mangelsdorf and just before Hadid’s shockingly early death, I had been sitting in the rabbit warren of ZHA’s offices in Clerkenwell, in a conference room, listening in on a game of conversational ping-pong between Mangelsdorf and Patrik Schumacher, as I invited them to delineate the ways in which their different methodologies and aspirations have complemented and clarified each others’ practice over the 20 years they have worked together. Mangelsdorf: ‘I remember Rome [Maxxi] being this collection of U-shaped spaces: one would lie on top of the other and you could see that the walls and the floors of those U-shapes become the structure. The challenge as an engineer is - how do I keep that? It’s about the integration of architectural form and structural form that starts that dialogue.’

Details and view of the Riverside Museum, Glasgow

Details and view of the Riverside Museum, Glasgow

Schumacher: ‘We like to make the visible architectural presence as much as possible coincident with the structure itself, and the necessary systems, and avoid if possible wrapping up all of this in sheet rock or some other surface, which then creates a different figure. Why? Because there’s more trust in that overall artefact and you avoid the sense of being in a stage set.

Details and view of the Riverside Museum, Glasgow

Details and view of the Riverside Museum, Glasgow

‘In Rome we had the big long walls, bridges and cantilevers where you can see directly into the structure. And in Wolfsburg [the Phaeno Science Center] we had the big cones that hold up the building, and you see the waffle slab, you see the cells; the next level up you see the big, steel, space frame and how this is tracing the irregular reality of the shape, of the site. It transforms into a distorted, irregular building shape and… you get this kind of hologram image. When you just cover [an interior structure] on the surface you don’t get this sense of how different scales and grains connect.’

Details and view of the Riverside Museum, Glasgow

Details and view of the Riverside Museum, Glasgow

But these were early buildings - buildings created at a time when structures were severely limited by what skills and technologies engineers had available. Over the years ZHA and its engineer collaborators have been quick to take advantage of new technologies, new digital computation and analytical software to expand and enrich the entire process. But the technology is always placed in service of the ultimate building and the experience of the building.

Says Schumacher: ‘There are capacities we have now developed between us as architects and the engineers with whom we collaborate in terms of… adapting the architecture to conditions - site geometry, access, flow, environmental parameters and variations in the spans and heights. All of this leads now to an architecture that is much more supple and differentiated and adaptive.’

As an exemplar of current computational capacity Mangelsdorf holds up the Beijing Airport competition design, which they won three years ago, as ‘probably the most exciting project I’ve ever worked on… We explored a completely new combined model of lighting, heating, structure, way finding, airplane traffic, that defined the building form. It was truly multidisciplinary.’ Though the full integrity of the design may not have manifested itself in the finished building [it was handed over to Chinese contractors over a year ago], its space-age sinuousness and structural lightness owe more, according to Schumacher, to the more organic engineering of the 19th century than that of the modernist 20th.

Details and view of the Riverside Museum, Glasgow

Details and view of the Riverside Museum, Glasgow

Says Schumacher: ‘The engineers always knew, in the 19th century, that if you have a structure that is subtly adaptive to the mobile flows and forces it was because there was more labour time available and less luxuriousness with respect to materials.

Engineers knew that even a simple system like a beam could be deeper in the centre and then it could be shallower at the edge… they could play with shapes according to what they understood about the distribution of weight, using mostly organic forms.

‘In modernism,[engineering] was dominated by laboursaving machining, so then you get [restricted by] fabrication and extrusion logics, repetition logics, one-size-fits-all logics, and you lost a lot of that elegance. And now we can bring it back, but we don’t need all that handcraft and labour to bring it back.

Details and view of the Riverside Museum, Glasgow

Details and view of the Riverside Museum, Glasgow

We can use sophisticated machinery to bring it back. And on top of this we have a degree of suppleness… We can work with irregular set-ups and compute the differentiations. That gives an organic character to the space but also tells you about the space.

As you see the beam swelling you know that the space becomes wider, or that the deepest part of the beam is also the centre of the space, which you might not see in a big hall that is otherwise cluttered with walls. This is what I mean by making a structure transparent: it’s making it information rich.’

Mangelsdorf: ‘Everything you have just outlined is about performance in a way - engineering performance and performance of the space that we can test in various ways - and I think that’s where the collaboration comes together. Because, obviously, Patrik’s team will test it against the architectural performance parameters that have been set for the space but we feed into that the environmental parameter studies or the structural parameter studies. Or there are compound parameter studies at times where we distil [requirements for] light and humidity and other factors into compound, people-based parameters that are about wellbeing or comfort. Or you can even link it to productivity if you want.

CGIs of Beijing Airport

CGIs of Beijing Airport

‘If you look at another project, the Orla office building in Warsaw, it’s a super-simple building, a very tight site, and a very tight budget, with rather onerous environmental conditions. Here we developed an entire architectural narrative out of [enhancing or deflecting] the sun’s angles with the relief of the facade. That’s where architectural design and performance-based design - our knowledge of environmental performance - converge and enhance a project.’

Schumacher: ‘It’s like a serendipitous…synergy between two factors. What the structural optimisation delivers is of a character we desire for our aesthetic and semiologic captivation of the spaces. If the form is rigorously optimised according to certain criteria, it delivers elegance and beauty, which is often superior to what we could have invented [by hand/eye]. In my theory of beauty we have to recognise that we are trained to respond to forceful, coherent artefacts… We look at something like this [he shows designs for Beijing Airport’s interior] and we sense there is orchestration that is meaningful and purposeful.

CGIs of Beijing Airport

CGIs of Beijing Airport

That’s what a project coming out of rigorous, sophisticated engineering delivers: a complex, variegated order we find attractive or beautiful but that also gives us the social order, which maps itself into these spaces. So, for instance, rather than being given a [building with an] array of 200 neutral boxes [rooms], whether they are ground up, or north, east or west, we give them a range of varied spaces that communicate their place in the structure: the lower ones are more robust and have this heaviness; at the top they become more filigree. That helps us to map the different functions on to something where they become recognisable rather than becoming disorientating.

‘It’s arbitrary semiology but it’s an ordered semiology. It can be expressed in many different ways. Sometimes there are zones in concrete, zones in steel, and the primary route becomes the zone in timber. Architecture lives on this. Rather than making it cream, yellow or blue as an arbitrary coding, it’s performative, and already associated with a material. It becomes an orchestrated palette for an orchestrated, semiological, phenomenological world of orientation, and recognition of identity. It’s always been to some extent like this: that ornament has always lived off the technical rather than fighting the technology.’

CGI of the interior of Beijing Airport

CGI of the interior of Beijing Airport

Orchestration is a key word here - it brings in the underlying dynamic between all the different parties that have to work together to achieve the best possible architectural, environmental and experiential result. Says Mangelsdorf: ‘The processes that sit behind all of that are highly curated and edited. You have to have the designer, the architect and the engineer working together and steering this process in such a way that this orchestration is eventually legible.’

He brings up the example of Glasgow’s Riverside Museum as an ideal technical and aesthetic orchestration: ‘The roof is a folded plate and we developed that in the first meeting. It’s not a regular folded plate that goes from A to B. It morphs and widens. It’s irregular and it goes around a corner twice. Ultimately, what we found as we developed it further was that it was very robust and it was even pretty flexible.’ And, adds Schumacher: ‘It gives a clear direction to the space.’

Riverside Museum opened in 2004, so the engineering technology was of an even earlier vintage. Would such a dynamic but fairly simple engineering solution be proposed now, with all the computational wizardry available? Mangelsdorf believes so: ‘The approach behind it is still the same. I’d say the tools we have at our disposal now make this process easier, more interactive maybe, faster, but the thinking is the same.’

Schumacher: ‘By the time of Riverside - 15 years ago - our thinking had already emancipated itself from the need to cut every structure into discrete, simple and independent systems for the sake of simple calculations without computers.’ Mangelsdorf: ‘Now [we have] this ability to weave [structural and aesthetic requirements] into an analytical process that is much more interactive and allows us to move one step beyond just structure. It allows us to bring various disciplines together - engineering and architectural - and create models with which we can actually investigate more than just one stage. We can go beyond that and optimise form, facade and envelope. This is where it becomes interesting, and we can bring in environmental characteristics and environmental factors - building physics, if you will.’

The project ZHA is completing in Riyadh - the King Abdullah Petroleum Studies and Research Centre - represents yet another evolutionary leap, adopting a more overtly biomimetic approach: the structure’s crystalline form is highly calibrated to maximise daylight, function and shade. The outer shell is both protective and porous, bringing daylight into interior spaces and creating buffer zones for smooth transitions from outside to in. The pair are clearly excited by recent advances in biomimetic computation, allowing architects, engineers, and scientists to replicate the extraordinary complexity of biological systems - and even generate new forms through sophisticated programming.

Images of the City of Dreams project in Macau, China, designed by ZHA with structural engineering by BuroHappold

Images of the City of Dreams project in Macau, China, designed by ZHA with structural engineering by BuroHappold

Says Schumacher: ‘The biomimetic [evolution] is… so wonderful, it’s so inexhaustible. It’s nature as the great original designer. It’s always inspiring to look at… I was speaking at a biomimetic conference in Stuttgart recently and what’s wonderful is to get engineers, architects and biologists exchanging their research and forming teams. Biology is a much larger universe but a vernacular closer to our purposes.’

But it’s perhaps not surprising that, while these two early adopters are enthusiastic at the thought of computers being able to self-generate new kinds of biomimetic architecture - using the latest gimmick, ‘genetic algorhithms’, for example - this prospect elicits a great deal of concern elsewhere,not just from those wary of handing over the structuring and programming of our world to robotic systems, but from the architecture and engineering professions in general, fearful of being computed out of a job. Schumacher dismisses the doubters: ‘The tools in themselves don’t help you put on the table what to analyse. [Human] trial and error does.’ Adds Mangelsdorf: ‘What a genetic algorithm does is it works as a generational, evolutionary [system]. You set boundary conditions and you have an algorithm that starts testing things against those boundary conditions and fitness criteria.

It will discard the bad ones and continue with the good ones. The tool is beautiful and powerful but it’s only as good as the one who is driving it. This is what we are continually getting towards: parametric engineering is really giving us incredibly powerful tools that allow us to optimise, to analyse and to select. But it is not designing a building for us. What designs the building is how we define the boundary conditions, the fitness criteria, and it’s a very individual thing.

‘Even in engineering if you put three engineers in a room you will get four different opinions. Only some of it is physics. Quite a lot of it is other criteria - material choices, climate - there are numerous criteria through which you can evaluate an engineering solution. We as the designers, engineers, and architects have the big task here of being the curator. ‘It’s our task as designers to find the best compromise. It’s up to me to listen to my clients and find out what’s the best solution for them… It is effectively an analogue computational design approach.’

Schumacher: ‘For us, we would rather compose in this kind of logically constrained space rather than composing more freely, which we did when we first used computers, because we didn’t have these tools. It gives a certain formal rigour.

We feel that [in this way it enables us] to get a handle on more constraints not only pragmatically, because we know that it can be built, but also aesthetically, because we know it can be built with lightness. We also find it more beautiful when we compare the models. We have an intuitive sixth sense about order. That’s something we actually call “serendipitous congeniality”; we are not fighting each other. There is a coincidence of interest. You [the engineers] want this form for efficiency reasons, and we would pick the same form for beauty reasons, for expressiveness and also place-making.’

Mangelsdorf: ‘Occasionally we also break the rules. We are not always following these stringent logics all the way through. At times there is an adaption of pure logic, because certain site conditions or spatial conditions are necessary.’

Schumacher: ‘For example, with Beijing Airport, we had a very beautiful structure and that makes the space. If you don’t work with structural principals and logics you are lost but, at the same time, [we adapted the model to use daylight] as a navigation device because the light guides you through the building.’

Mangelsdorf: ‘With Beijing, we developed a multilayered story, which had the light performance, the shading performance, the orientation with parts of the shading elements, together with the structural logic. We broke boundary-condition rules where we didn’t have to, say, reinforce a piece of structure, so that it allowed us to get a more beautiful and more efficient foot point for the structure. So we started shaping the structural foot points in certain areas, and they are maybe not what the [initial] model would have given us, but I don’t mind that. Call it compromise… something gets pulled a little bit.’

Schumacher: ‘Nature is the same… What I say now is that we aspire to this rule-based generation of projects. That’s why we started to distil the rules, and I think we prefer the scripted proliferation on variations in the system and the scripted negotiation of parameters. Why? Because that’s more supple, more rigorous, more nature-like, and rarely can we compete with that in a tool.

Images of the City of Dreams project in Macau, China, designed by ZHA with structural engineering by BuroHappold

Images of the City of Dreams project in Macau, China, designed by ZHA with structural engineering by BuroHappold

‘Talent is that sensitivity for rules, for principles, for principled action in a drawing, so that, somebody can sketch a situation… and intuitively sense that this figure has to have a different centre of gravity…whether moving to one side or the other.’ Mangelsdorf: ‘It is about making the choices: you may get to a point where you have conflicting rule sets, and those conflicting rules mean some things have to be stronger and some things have to be weaker. The adjustment often has to be a guided adjustment. The machine doesn’t do that.’

Schumacher: ‘A lot of people worry about this and see this as a kind of disempowerment, but I see it as an empowerment in experience.’

Mangelsdorf: ‘Me too. Totally… it’s absolutely beautiful for us, this kind of approach. For instance, we can start talking with Patrik’s teams through scripts, and we exchange scripts very often and just communicate through those and we build in our rules… There is this reactiveness to physical parameters or structural loads, or whatever you want to call it, that allows another layer of shaping things. You ask about tools: we have a whole box of tools that we plug into this process. We react to whatever we get and we send it back. It becomes highly interactive.’

Images of the City of Dreams project in Macau, China, designed by ZHA with structural engineering by BuroHappold

Images of the City of Dreams project in Macau, China, designed by ZHA with structural engineering by BuroHappold

Schumacher: ‘In this way, we get a more intuitive and playful grasp of structural dependencies, and we can develop an initial approximation of principal forms and relations, [we can see that] this column needs to be thicker and that thinner. The exact quantification we can’t deliver [that’s up to the engineer] but we also like the engineers to confront us. It used to be that false ethos of collaboration, that the engineer would be sitting quietly waiting for instructions on every shape or form or wanting too much to fulfil their [engineering] desires, and then force the structure to comply. For us, it’s also more satisfying [this way]. We need in a sense a tough pushing from the engineer… we want more resistance and guidance.’

Mangelsdorf concludes: ‘And that generates a dialogue. We go back to the beginning. We contribute quite strongly to the formulation of the orchestration of those different parts because pushback just for pushback’s sake doesn’t work.

‘We have worked together for 20 years and it has been extremely exciting, because some of it goes a little bit against engineering principles. The engineering becomes more pure and more rigorous than previously. We are at this point of synergetic working together that leads to an expression of both engineering and architecture.’