A closer look

Museums are getting smarter about bringing their audiences closer to the subject, and even closer to each other, finds Veronica Simpson.

'Museums are places where time is transformed into space,' says Nobel prize-winning writer Orhan Pamuk, in a short filmed monologue for his Museum of Innocence.

Not content with creating entire fictional worlds in his novels, Pamuk decided to conjure a physical space alongside the imaginary one of his Museum of Innocence novel. He conceived and developed both book and museum over the same time period, starting in the early Nineties. Through both writing and installation, Pamuk wished to evoke the vanished glamour of Istanbul in the Seventies, a time of economic growth, increasing liberalism, consumerism and lavish parties. He collected objects either strategically or serendipitously and used them to construct a narrative around his young, affluent protagonist, Kemal, and the intense but doomed romance that blossoms between him and a young, distant relative.

The Museum of Innocence at somerset house, until 3 April. Photo: The Museum Of Innocence

Though the book was published in 2008, the Museum did not complete until after Pamuk found the right 19th-century building in the heart of Istanbul's Beyoglu neighbourhood, where much of the narrative is set; filled with 1,000 objects, it opened in 2012 and went on to win the 2014 Museum of the Year Award.

Each chapter of the book is represented in his museum as a vitrine, with the relevant objects, images and textures presented, like one of Joseph Cornell's evocative boxed tableaux.

A highly edited but still enchanting version now appears in Somerset House: 13 of the 53 chapters /tableaux, along with the aforementioned filmed monologue and a haunting documentary that traces the very real routes taken by the fictional Kemal as he roamed the streets of Istanbul at night, mourning his losses.

Grouped artefacts tell the stories of fictional characters from Orhan Pamuk's novel. Photo: The Museum Of Innocence

You don't need to read the book to enjoy that voyeuristic sense of guilty pleasure you get from imagining the lives that resonate around the objects in a vitrine: for example, the illicit ménage a deux implied by a rusting antique metal wash basin, complete with vintage razor and brush, and a single vivid red lipstick -- its colour instantly evoking a flamboyant femme fatale of the mid-20th century.

The experience of gazing in these vitrines brings you up close and personal with the lives of real and imaginary people, whether they are Pamuk's characters, fantasies entirely of the visitor's making, or the real individuals who once owned and treasured the black and white photos of glamorous dinner parties, or clasped the ornate opera bag embroidered with silver thread.

Though Pamuk's museum is a very personal take on how a past space and time can be brought to life, it is probably all the more powerful for its unique focus and idiosyncrasy.

But he has touched on a trend that is pervading the whole heritage and culture sector, as curators seek new ways to draw audiences close and intensify engagement. Instead of focusing on the usual culturally conservative narratives of past heroes and myths, and placing their subjects -- and objects -- on pedestals, the emphasis has shifted so that the whole of humanity, and all of human experience, seems to be up for examination and interrogation.

I have sung the praises before of Museum Rotterdam's contemporary exhibition arm and its ongoing dedication to a programme that reflects the voices of ordinary Rotterdammers, along with their very real issues and challenges.

But I had reason again to admire its work on a recent visit to the city. Curator Nicole van Dijk was just setting up the final displays in the museum's permanent space -- a rippling glass, Rem Koolhaas-designed building, which is now home to Rotterdam's local government offices as well.

The museum has been without a permanent home for the past couple of years, and responded by initiating a kind of social and cultural inventory of the city, resulting in some fascinating pop-up exhibitions (covered previously in FX). In the course of its research, via social media, workshops, performances and events, the museum generated a huge amount of information about Rotterdam's diverse communities and economies. For its new home, Museum Rotterdam has mined this rich seam of information to come up with a new exhibition that gets even closer to the individual citizen.

Orhan Pamuk. Photo: The Museum Of Innocence

In fact, it follows the stories of five ordinary Rotterdam characters. These are genuine citizens, such as Max, a Rotterdam-born urban gardener, who has helped to regreen parts of the city through both orthodox and unorthodox methods; or Zeynep, a young woman who was born in Rotterdam of Turkish parents, and who is just launching herself as a fashion designer; there's Kamen, a Bulgarian builder, who has lived in the city for 11 years, but who travels back regularly to his Bulgarian home town in his van; and Joyce, who is in her fifties, originally from the Caribbean-Dutch island of Curaçao, but whose life now revolves around various communities of Rotterdam's elderly, for whom she is a carer.

All five individuals are represented by a large-scale model of themselves, taken from 3D scans and robotically carved out of foam. These figures stand atop a three-tiered presentation that aims to reveal the city through their eyes. Photos of shops, parks and places they frequent are pasted on to the top tier.

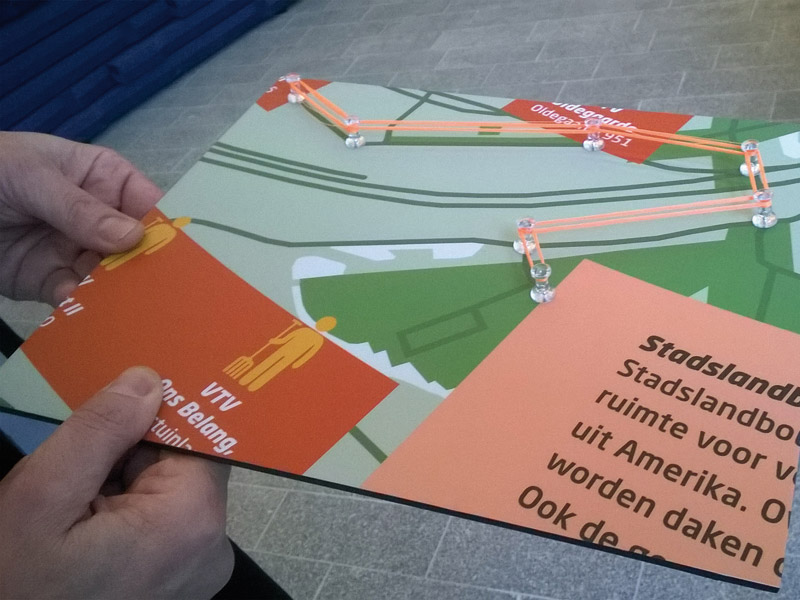

Below that there is a 'mind-map' graphic representing the network of people they are connected to within the city, while on the bottom layer, a similar but more complex graphic maps all their key venues for work, rest and play, on a plan of the city.

Digital tools combine with this analogue presentation in novel ways -- each 'ordinary hero' has had their journeys across the city recorded on an app and their routes and venues will be mapped on to the accompanying city via coloured string. The results of this exercise are illuminating -- Max, for example, travels across the entire cityscape on his bike.

'He owns the city,' says van Dijk. While Kamen either stays close to home or gets out of town altogether, to his construction jobs.

Through these people and their stories, van Dijk hopes to kick-start a whole new era of engagement for the museum, staging events, seminars and performances in the space to knit the community closer to the museum and each other. In this way, the museum becomes a space where people find time for their fellow citizens. How revolutionary is that?